Louis S. Warren (83 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

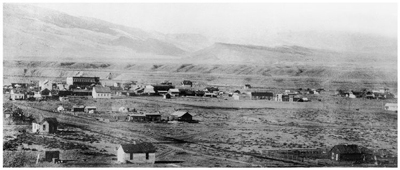

Cody, Wyoming, c.

1905.

Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Such close attention was typical of Cody's business manner. But if it brought him success in show business, it did him little good in the town business. His show made profits, albeit unevenly. The town did not. “I am doing my best to raise money,” he wrote Beck. “I tell you it keeps me sweating blood but no use getting discouraged. [I]f you can only protect our name and credit, I will say thank God.”

92

Failure to complete the canal in a timely fashion could be disastrous. Officials “will make an unfavorable report of our canal if something substancial is not done,” he warned Beck.

93

The result of cumulative poor assessments would be the loss of their segregation, and their investment.

Despite the town's halting development, Cody hoped it would yet provide him means to retire from show business. In 1903, he journeyed with the Wild West show to England again. Ticket sales were nowhere near what they had been on earlier European tours, and Cody spent long days sitting in his private railroad car. “I am going to get out of this business that is just wearing the life out of me,” he wrote his sisters. “[T]here is such a nervous strain continualy. And the thing has got on to my nerves. And this must be my last summer.”

94

He was too tired much of the time even to be convivial. “I do not go to hotels any more for I haven't the strength to be even talked to. The only ray of pleasure I have is when I get to thinking of dear old TE [Ranch] and the rest I am going to get there.”

95

By this time, it was becoming abundantly clear that Cody and his various partners in the Big Horn Basin had vastly underestimated the cost of irrigation. The Cody-Salsbury plan to irrigate 60,000 acres north of the Shoshone River proved much too expensive even for the most successful of showmen. When Cody and Salsbury commissioned an engineer's estimate of the costs, which included irrigating lands north of the town and providing the town waterworks, even the cheapest alternatives were estimated at a staggering $742,000.

96

Even if they sold water rights to every acre at the highest price the law allowed, their profits would amount to only $158,000, and that only if there were no other expenses along the way: no lawsuits for flooded fields or washed-out headgates, no recruitment of settlers or advertising. By 1901, it should have been clear: irrigation did not pay.

And yet Cody continued to pour money and effort into developing the Cody-Salsbury segregation. Part of the reason was that he had an eye on the Mormons, who had developed irrigation systems not only in Utah but downstream on the Shoshone River, at the town of Lovell. Since arriving in 1900, a small Mormon colony had succeeded in building a town and began eyeing nearby parcels for an expansion. First in their sights was the Cody-Salsbury segregation across the Shoshone River, which they claimed should be returned to the public domain because Cody and Salsbury had yet to deliver the water they promised. Cody, who had faced off against imaginary Mormons in his stage plays, now spent considerable effort keeping his segregation from falling into their hands.

97

But if their expanding horizons made him suspect there was potential for more cash in irrigating the desert, he drew the wrong conclusions. Mormon irrigators had a critical resourceâcommunal laborâwhich Cody town did not. Farmers in Cody wanted the ditch dug for them; Mormons dug their own, collectively, as part of a greater spiritual effort to reclaim the wilderness. They were not fixated on how much money the ditches could make. They were, rather, bound by a spirit of collective religion.

Distracted by the Mormons, Cody appears not to have realized that his own frustrations in the irrigation business mirrored those of other capitalists. From 1894 to 1923, only one in twenty Carey Act projects made a profit. Ditch investments across the arid West paid so poorly that few investors could be found. Private funding of western settlement all but evaporated.

In 1902, Congress sought to remedy the shortcomings of the Carey Act with the Newlands Reclamation Act, a law that dramatically remade the landscape of western irrigation. Overnight, digging and financing large-scale irrigation works became a federal responsibility, administered through a new agency, the U.S. Reclamation Service.

98

The Cody-Salsbury segregation was ideal for a large-scale irrigation project, and officials from the new agency were after it almost as soon as they had offices to work from. A dam across the Shoshone River would allow them to build a canal across the high northern bench and water a huge tract of land for settlers. Cody himself had made the same assessment, but he was unable to find the funding he needed, and the financial resources of the Reclamation Service far outstripped his. Where he scrambled to raise money in the tens of thousands of dollars, the government planned a network of dams, tunnels, canals, and laterals, and within months had appropriated $2.25 million for the project.

99

Giving up the segregation was not easy. But as William Cody saw it, if the cards fell right, the government takeover would not hurt his interests. The irrigation works were a very expensive means to an end: making desert into arable, valuable land. He had other prospects on the north side of the Shoshone, including another townsite. As things stood, it was worthless. If the government brought water, though, he could make a tidy sum selling lots. He would not have water rights to sell, but having all those rights to sell along the Cody Canal had not made him a dime. The trick was to get somebody else to pay the high overhead of building and maintaining the canals. The water, when it came, would turn his desert land to gold. Salsbury and Cody ceded their segregation.

But William Cody, ever the show director, was still convinced he could hurry matters along. He inserted a condition in the documents, stipulating that the federal government had to begin construction of the canals on the north side of the river by January 1, 1904. Should they fail, he would reclaim the segregation and move ahead with private capitalâor so he thought.

The government failed to begin construction in time. Cody reneged on the cession and tried to take the segregation back. He had powerful allies in Wyoming, including the governor, Fenimore Chatterton, who saw the showman as a source of cash for a tax-starved state. As the governor told officials, “It has been our experience that Wyomingites through practical business methods rapidly push things to completion, and it is the intention of the land board to stand by Col. Cody, one of our citizens who has demonstrated his ability to do things.”

100

Allegedly, that “ability to do things” included the recruitment of new investors, and it was the prospect of new money that made Cody anxious to keep his options open on the northern bank of the Shoshone River. While touring Britain with the Wild West show in 1903, Cody persuaded a group of wealthy Englishmen to examine the Big Horn Basin. Whether they saw this trip as merely a vacation or an investment tour is not clear, but according to Cody, they struck an agreement. If the canal venture looked profitable, he explained a few years later, “they were to finance and build the North Side canal, for which I was to receive $75,000 in cash, besides a portion of the stock of said company.” In late 1903, Cody announced that he had secured $3.5 million in new investment.

101

But back in the United States, various old allies became alarmed that Cody, by reneging on his agreement to give up the segregation, was going to delay the federal government's development of the north side. The Burlington & Missouri River Railroad had built its spur line to Cody town directly through the Cody-Salsbury segregation. Irrigation would mean a vast increase in the area's appeal for settlers and a dramatic increase in traffic along the rails. Buffalo Bill and his English party had barely reached the West before they were waylaid by representatives from the railroad. “On my arrival at Chicago with these gentlemen I met some of the Burlington railroad officials who were very anxious for me to turnover the North Side proposition to the Reclamation Service.” Further down the line, the encounter was repeated. “At Omaha I met other Burlington officials who were very anxious for me to do the same.” Cody assured railroad officials these new investors had the money to see the job to completion, and insisted that he and his guests at least continue the tour of the Big Horn Basin.

Cody knew well that the railroad companies would not look after his interests, and he could hardly have been surprised that Burlington officials wanted him to drop the segregation so the government could build waterworks all along their railroad line.

But there was another surprise, and a greater disappointment, waiting for him at the town that bore his name. Cody settlers, still struggling with the inadequate, privately funded Cody Canal, and chagrined at the failure of the Shoshone Irrigation Company to provide a modern waterworks for the town, now bridled at William Cody's meddling in the government project across the river.

102

“On our arrival at Cody the citizens of this place called a mass meeting for the purpose of getting me to consent to letting the Government, as they called it, have the North Side segregated lands for which I held a concession.”

103

As the Republican Club of Northern Big Horn County put it, only government money could guarantee “the construction of this giant system” of ditches which would “bring to our community thousands of energetic citizens, and will add millions of dollars to our property valuations” through “the development and creation of fine ranches and homes.”

104

The message to the showman could not have been clearer: get out of the way.

As Cody recalled it, “the Burlington officials and the citizens of Cody and Garland [another town to the east] were so anxious to have the Reclamation Service handle this proposition that I finally consented to their wishes. I gave my English friends a hunt in the Rockies and they returned to England. Seeing how I was pressed to give up the enterprise they did not blame me for asking them to abandon the proposition.”

105

The English hunting party likely had no strong interest in the investment. Cody may have floated news of the $3.5 million investment as a bluff, hoping to force the Reclamation Service to begin construction of the north side canal. If so, in the end, the ruse worked best on the railroad officials, who gave Cody a half interest in their town site of Ralston, thirty miles east of Cody town and on the north side of the Shoshone River, to persuade the showman to give up his segregation.

106

If it was a bluff, then it was about all he had left. By late 1903, Cody and his partners had lost a lot of money. Unless the Englishmen believed that water would somehow grow their investments the way it grew alfalfa, the ditch investment could hardly have been appealing. Even with the Cody Canal mostly complete, William Cody swore under oath in 1904, “We are behind on the canal, as our books will show, to the tune of about $180,000.00”

107

He never made that money back.

In February 1904, Cody released the segregation for good.

108

Thus far, the irrigation business had not broken him, but neither had it provided the retirement, farm, and home he had imagined it would. He now at least had a claim to another town site on the north side. When the government water came through government ditches, he would sell the land. He was not yet done with the Reclamation Service.

In the decade he had been active in the Big Horn Basin, his aspirations for retired domestic bliss had suffered bruising setbacks. He was about to inflict another. In January 1904, as he grappled with abandoning his segregation, he filed another set of legal papers in Cheyenne, making him plain-tiff in his own lawsuit against his wife. Buffalo Bill Cody, defender of the settler's cabin, had filed for divorce.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Showdown in Cheyenne

HAD CODY'Sdivorce petition succeeded, it would have marked his second dissolution of a long-term partnership in recent years. When Nate Salsbury died after a prolonged illness late in 1903, William Cody found himself unhindered by the man's professional demands for the first time in eighteen years.

Cody still had a managing partner in James A. Bailey, of Barnum & Bailey, who arranged the show's travel schedule and transportation. Salsbury himself had brokered the agreement with Bailey in 1894, when he realized that failing health would keep him from traveling extensively. But Bailey was a behind-the-scenes operator, with no desire for the limelight. His extensive inventory of railroad cars made him a worthwhile partner. He managed the transportation for the show, and he was essentially the local manager in every town where the show appeared.

1

But Bailey was never a friend. He did not link his name to the show, was less invested in it, and had no personal influence over the star. In this sense, Salsbury's absence left Cody shorthanded, and it may have been responsible for some of his poor decisions. The relationship between Cody and Salsbury was often strained. Their partnership in this respect was akin to that of Rodgers and Hart or Lennon and McCartney, that is, famously creative and notoriously difficult. As co-owners of the show, Salsbury and Cody made decisions about it together. The managing partner was sometimes more careful than Cody in watching the show's bottom line. But even if the Big Horn Basin was a bad investment, Salsbury had not only joined the Shoshone Irrigation Company but encouraged Cody to find other investors, too. Salsbury himself made some disastrous choices for the show, dreaming up the money-losing Ambrose Park appearance of 1894. The next year he created

Black America,

which proved an expensive failure. Both of these drove Cody to invest even more time and effort in the Big Horn Basin in hope of making up show losses.

Tensions between the partners grew. Salsbury knew he was dying. His illness made him less temperate. Perhaps Cody showed signs of impatience. The managing partner anticipated a split with Cody, or a posthumous legal assault on the Salsbury heirs. Sometime after 1901, Salsbury sat down at his home in Long Branch, New Jersey, to dictate (or possibly type himself) a scathing history of his career with William Cody and the Wild West show. 2

What he wrote was not for publication, he said, but if it were, he would call it “Sixteen Years in Hell with Buffalo Bill.” His grievances were many, starting with Cody's hedonism. “Cody makes a virtue of keeping sober most of the time during the Summer Season, and when he does so for the entire season, he looks on himself as a paragon of virtue and self-abnegation.” But when he drank, “he forgets honor, reputation, friend, and obligation, in his mad eagerness to fill his hide with rot gut of any kind.” As a rule, said Salsbury, “he would keep at it until he fell so sick that he could not move, or as he used to put it, âHis liver flopped,' and then would co[m]e the strain of getting his head reduced.”

Cody's indulgence was nowhere near as irritating as his permanent sense of entitlement. “When he sobers up a little, he is so conceited as to imagine he has had a perfect right to get drunk, no matter at what cost to his associates in business, and takes it for granted that he is so great a man that all the world excuses him because he is a hero and an âOld Timer' who saved America from going back to the wilderness [as] Columbus found it.”

Combined with his womanizing, these habits endangered the reputation of everybody in his orbit. In Rome, Cody visited the homes of dignitaries when he was so drunk “that he could hardly get into his carriage,” and, worse, with a woman in tow. Ushered into the drawing room of the British minister, “he remarked to his concubine that âWe can beat this in Nebrasky at a fifty-cent admission shakedown.”

Salsbury grimaces through his typescript memoir with his head in his hands. “And this is the gentleman that ladies and gentlemen have delighted to honor. Bah.”

3

This “Tin Jesus on horseback” demanded continual attention and adulation. He had “abused every man in our employ who ever showed that he did not regard the Hero as the head and front of the Showman's Universe.”

4

Salsbury remarked on the new biography of Cody written by his sister, Helen Cody Wetmore. She called it

Last of the Great Scouts,

“and if she will only insure the verity of her title page,” wrote Salsbury, “she will be doing humanity a service. A man may be a âGreat Scout' and a dââd rascal at the same time.” Salsbury had had a bellyful of Cody's frontier heroics. After all, “as a private soldier during the Civil War, I smelled more powder in one afternoon at Chickamauga, than all the âGreat Scouts' that America has ever produced ever did in a lifetime.”

5

Cody's misbehavior and ungratefulness were all the more insulting, in Salsbury's eyes, because Buffalo Bill was his creation, “a commercial proposition that I discovered when I invented the Wild West, and picked him out for the Figure Head.” He boldly (and incorrectly) proclaimed, “I invented every feature of the Wild West Show that has had any drawing power.” To hear the managing partner tell it, he could have been just as successful with any number of other men as his star. “There were others, and there will be others,” he wrote, pointing to Cody's many imitators. If any of them “had had the good fortune to be good looking, tall, dashing, and the subject of romantic tale telling for a decade, there would have been some other commercial propositions that could have been developed.”

6

More than anything else, Nate Salsbury wanted the world to know that he, the manager, was the reason for Buffalo Bill's worldwide fame. In 1885, on the train from Montreal to Toronto, Salsbury promised Cody “that I would land him at âthe foot of the throne of England.' ” Two years later, Cody performed before Queen Victoria. As we have seen, Cody had that ambition in mind before he ever met Nate Salsbury. But the managing partner recalled the idea as his alone. “Of course, he forgot the promise and took the kudos.”

7

Salsbury's rant, though wounded and defensive, still contains some suggestions about the sources of Cody's enduring appeal and creativity, particularly his childlike enthusiasms which sometimes veered into childish impulsiveness. “It would not be so bad,” wrote the partner in one of his more reflective moments, “if he had the common intelligence of a child, or if he could remember from one day to another the experience he has already passed through.” At least then the show's star would not need to spend large amounts of time “apologising for his BLUNT WESTERN WAYS. . . . I have heard so much of the manly behavior of the WESTERN man since I have been mixed up with him, that I might believe in it, if I did not have Cody for a partner.”

8

The managing partner's account is so wry and vivid that Cody biographers may be forgiven for finding it irresistible. Watching the downward trajectory of the Wild West show after 1900, it is easy to believe much of what rolled off that typewriter in Long Branch. In one of his last acts on this earth, the old comic Salsbury entered the debate that swirled around CodyâIs he a hero, or is he a charlatan?âand came down firmly on the side of the latter.

But for today's readers, perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Salsbury's story is how familiar it is. The drama of the sensible, businesslike manager struggling to contain the unappreciative star is a central narrative of modern culture. In the century since Salsbury's death, his bitter memoir has been echoed by the laments of managers for movie icons, athletes, and rock stars, including Fatty Arbuckle, Babe Ruth, and the Beatles. These stories resonate for audiences in part because of their grand psychological drama, in which the manager plays superego, the containing force, to the id of the star, thereby playing out internal tensions of the consumer era as effectively as a Greek tragedy.

More directly, the recurrent complaint of the manager about the star reflects tensions within modern entertainment itself, whose stars must appeal to mass audiences, a task which requires them to be in part products of professional booking, travel, and publicity staffs, and partly the projection of less quantifiable forces such as charisma and talent.

The tensions between manager and star that pervade Salsbury's account emerged in the era's popular literature at the very moment that Buffalo Bill reached his apogee. They were reflected in George Du Maurier's 1890 novel

Trilby,

which was the source of the Svengali legend. As we have seen, they were also at the heart of Bram Stoker's relationship with Henry Irving, and were central to the novel

Dracula,

which appeared only a few years before Salsbury wrote his account. Salsbury probably never read Stoker's novel. But by the end of his life, he likely would have sympathized with Stoker's fear that the man whose career he managed had drained him of all vitality.

Indeed, the comparison of Salsbury and Stoker suggests the sense of awe and wonder, fear and admiration, that Cody's celebrity inspired in his closest partners. Even dripped in Salsbury's vitriol, we see Cody's irrepressible charisma. He is innocent, needy, and playful. His energy and his appetites are both boundless. Most of all, he exerts a curious power over his audience, which Salsbury exploits but which he only half understands. Recalling the meeting with Pope Leo XIII in Rome, Salsbury wrote that the Sistine Chapel was packed with worshippers that day. The pope, however, was drawn to Buffalo Bill. “As he passed the spot where Cody and myself were standing he looked intently at Cody,” recalled the manager, “who looked a picture in his dress coat and long hair.” The costume would have been ridiculous on anybody else. Cody was “the only man that I have ever known that could wear it without exciting laughter.” Cody bowed his head as the pope passed. “His Holiness spread his hands in token of his blessing, and the good Catholics around us looked with envy at Cody during the balance of the ceremonies.”

But in contrast to this sense of wonder, what haunts every word of Salsbury's memoir, are his half-articulated fears. He was terrified of a Cody legal assault, which might deprive him and his family of their share of the Wild West show, which he had worked so hard to sustain. “I have always realized the slender hold I have had on a man that would not scruple to throw me out at a moment's notice if he dared.”

9

For all Salsbury's complaints, he remained with Cody to the end of his life. Despite his intimate knowledge of Cody's many foibles, he too found the star irresistible. This fact seems to have puzzled Salsbury. His hastily composed memoir offers plenty of ammunition for any future showdown with Cody in court. But it also hints at Salsbury's unease with his own vulnerability to Cody's spell. The manager's vehemence could not disguise his own uncertainty. He wanted to believe he created Cody. But in the end, he feared he merely orbited him like all those ignorant fans, suffering the star to abuse him like some lackey. In Salsbury's hands, Cody emerges as beautiful and horrifying, magnificent and monstrous. In Salsbury's deathbed gaze, Buffalo Bill flickers between real and fake, hero and showman, demigod and demon.

SALSBURY'S MEMOIR remained private until years after Cody died. But in a curious way, many of his complaints about the man were echoed in public soon after, when Louisa Cody refused to grant her husband of almost four decades a divorce, and went to court to contest his petition. The trial that followed became a press scandal and the greatest public relations disaster of Buffalo Bill's long career. When William and Louisa Cody faced off in a courtroom, with their lawyers and witnesses, they scripted their marriage into dueling narratives, each battling for the sympathy of the judge. This was a contest in which the old storyteller and showman should have been an easy victor. But as the trial rapidly became a scandal in the mass press, it became a show of its own. Louisa Cody retreated to the settler's cabin, announced her loving devotion to a befuddled old husband, and pleaded with the court to make him desist from his scabrous attacks on her dignity, and especially on her marriage. Meanwhile, William Cody found himself cast as the circling antagonist, the savage bent on destruction of his own home. He was not to have the ending he wanted.

To understand why his suit for divorce went so wrong, we have to understand how central his image as a family man had remained to the Wild West show. To complete the narrative of frontier settlement, show programs emphasized not just his abilities as Indian fighter and hunter, but his accomplishments as a progressive pioneer, who not only conquered the West but domesticated it. His earliest show programs had featured pictures of his comfortable home in North Platte, where he had settled “to enjoy its fruits and minister to the wants and advancements of the domestic circle with which he is blessed.”

10

Cody expanded on this image in the 1893 program, by compressing a pair of images on one page, with a poem sandwiched between them. At the top of the page was an image of a savage frontier, a pen-and-ink sketch of Buffalo Bill “Lassoing Wild Horses on the Platte in the Old Days.” Below was a photograph of cattle grazing peacefully in front of the Victorian home and a barn clearly labeled “Scout's Rest Ranch,” with the caption “ âBuffalo Bill's' Home and Horse Ranch on the Old Fighting Ground of the Pawnee and Sioux.”

The narrative sequence was clear, from top to bottom: the progress from frontier to pastoral countryside, from war to peace, and even from open space to domestic space, had been made possible by Buffalo Bill.

The march of civilization is made all the more apparent in the movement from pen-and-ink illustration at the top to photograph at the bottom, and in the transformed nature in the two scenes. The animals in the bottom image do not need lassoing: they graze peacefully, and they even face the same direction, right, like words on the page. Perhaps the most salient component of the bottom image is Buffalo Bill's house, slightly to the left. It is a remarkable Gilded Age middle-class home, planted in the Nebraska prairie in front of a row of trees. Audiences would not need any prompting to associate this elegant home with a wife. The message was clear: by subduing the frontier, Buffalo Bill made homes possible. And he made it possible to keep womenâor better, wivesâinside them.