Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (27 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

There are “song songs” and “character songs.” A “character song,” which is basically free and is accompanied by an emotion or emotions, as in the case in “I’m An Ordinary Man,” must pretty much stay within the bounds of reason. In a “song song,” certain extravagances are not only permissible, but desirable. “Why Can’t the English,” written as it was, was definitely a “song song” and therefore contained a certain amount of satiric extravagance. The minute the same idea is written in a freer way, so that it almost seems like normal conversation set to music, those extravagances would seem definitely out of place.

36

This reveals that he was happy to change the song because he felt it was not in keeping with Higgins’s character; the lyricist himself saw the need for a transition of style—from a “song song” full of “satiric extravagance” to a “character song” with “broader scope and a longer line musically.”

This fits in well with the sources for the song’s four versions. The first is an early setting, with the music written out jointly by Loewe and Rittmann (mainly the latter) and the lyric by Loewe (see exx. 5.2 and 5.3 for extracts).

37

Since Rittmann’s handwriting is present, this manuscript must date from late 1955 at the earliest. All the clefs, key and time signatures, dynamics, and expressive markings are in Rittmann’s hand, as well as most of the notation.

38

The main piece of information to be gleaned from this is the rough date of the manuscript, rather than its authorship; it is not clear whether this is a fair copy of a previous Loewe autograph or the first time the composition was written down.

The original lyric is reproduced in

Appendix 2

. It is easy to see Harrison’s point about its supposed resemblance to “Mad Dogs and Englishmen,” which similarly contrasts the characteristics of the English with other nations. For instance:

Mad Dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.

The Japanese don’t care to,

The Chinese wouldn’t dare to.

However, it is also surely true that the revised lyric is not dramatically different in this respect. Nor does Lerner’s reasoning fit all of the revisions. For example, changing the couplet “Daily her barbaric tribe increases, / Grinding our language into pieces” into “This is what the British population /

Calls an elementary education” surely defines Higgins’s character more directly by giving his statement substance, rather than obliterating a Cowardesque element. If anything, one can sense Shaw’s socialist outlook in the new couplet, which attacks the institution of elementary education as the reason behind Eliza’s woeful accent and use of the English language, and by extension her meager lifestyle. The change from “Hear a Yorkshireman converse, / Cornishmen are even worse” to “Hear a Yorkshireman, or worse, / Hear a Cornishman converse” is another example of an enhancement process: the original is adequate, but the change propels the song forward more effectively because the “or” tells us that the next phrase will add something to the initial thought. The use of anaphora (“Hear” to start both lines) is also a stylistic improvement. Similarly, the change from “A national ensemble singing flat” to “I’d rather hear a choir singing flat!” clarifies the motivation of the line (flat singing is not Higgins’s focus, even though he detests it).

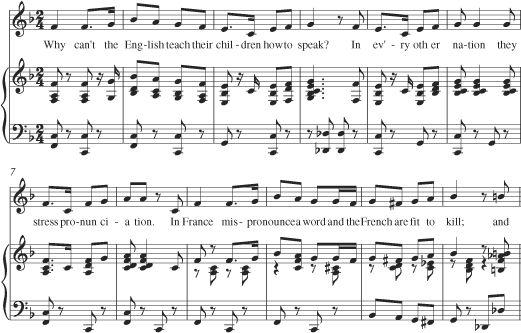

Ex. 5.2. “Why Can’t the English?” version 1 (excerpt).

Ex. 5.3. “Why Can’t the English?” version 1 (excerpt).

The refrain is more obviously similar to “Mad Dogs and Englishmen.” In particular, Lerner’s “Canadians pulverise it / In Ireland they despise it” has an air of Coward’s “The Japanese don’t care to / The Chinese wouldn’t dare to.” Yet the couplet cited by Lerner to explain why the original version was too similar to Coward’s song in truth seems only loosely related to it: “In Norway there are legions / Of literate Norwegians.”

39

So aside from a few similarities, there is little to link the songs.

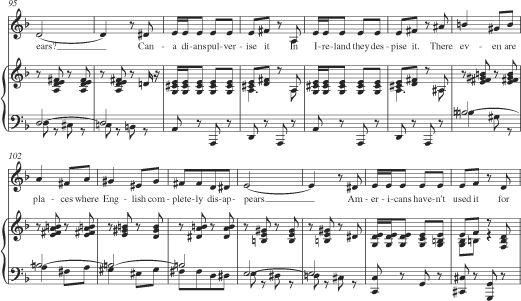

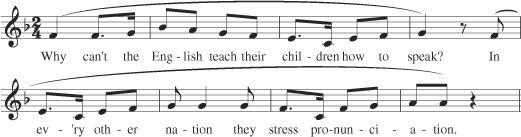

Ex. 5.4. “Why Can’t the English?” early version.

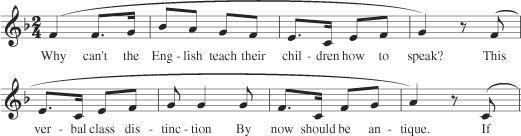

Ex. 5.5. “Why Can’t the English?” published version.

Ultimately, the main reason for the revisions was Lerner and Loewe’s ambition to make the number as effective as possible. To this end, both the lyric

and

the music were changed for the final version. The musical adjustments were small but significant, and suggest that the reason for the rejection of the early version was that the verse form did not suit the form of the music. Whereas the opening line of the refrain (“Why can’t the English teach their children how to speak?”) did not rhyme with the ensuing line (“In Norway there are legions”), in the revised version it makes a couplet with the second line (“This verbal class distinction by now should be antique”). This is much more coherent with the construction of the music. As

example 5.4

shows, the antecedent-consequent phrase structure of the music is at odds with the original lyric. Three lines of text are set to two well-balanced musical phrases—the first arriving on the dominant, the second returning to the tonic. The first line of text is twice the length of the other two, which are set to the second phrase of music. The word “speak” does not rhyme with the word “pronunciation,” even though they are related musically by their appearances at the ends of the two phrases. Stylistically, the original lyric is awkward, and the rhyme of “In every other nation, they stress pronunciation” is laborious.

The final version (

ex. 5.5

) overcomes these problems: rhyming the first two lines makes them reflect the musical structure more neatly, and the replacement second line again intensifies the social aspect of Higgins’s argument

with the reference to a “verbal class distinction.” The music is also strengthened by having one less syllable in the replacement second line, resulting in a quarter note at the end of the phrase rather than two eighth notes; and “[pronunci-]a-tion” is undoubtedly weaker than “antique.” In all, the issue is not whether the song resembled “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” but rather one of relative inferiority. The original does not serve the show as well as the final version, often because the initial lyric is about linguistic fastidiousness where the final lyric deals with a social concern.

A copyist’s score based on the original version also exists in the Warner-Chappell Collection.

40

The verse by this point had almost taken on its definitive form, with a few exceptions: Higgins says “Heavens, what a sound!” (rather than “noise!”) and “Take a Yorkshireman” rather than “Hear a Yorkshireman.” The couplet about the “writing on the wall” was completely removed (including the music) so that the verse goes straight from Higgins’s “I ask you sir, what sort of word is that?” to the chorus via a new two-bar introduction. The refrain, however, still retained its original poetical structure, with some amendments to the lyric. The couplet dealing with the Germans was expanded slightly and brought forward to replace the weak lines about the French.

41

Lerner also worked on the image of the Irish, taking the lyric closer to its final form and removing the Canadians from the picture: “The Scotch and the Irish do some / Pronouncing that is gruesome.” The Norwegians have gone, and in their place Lerner alludes to the Orient and introduces the joke about the French with the musical

tacet

: “With ev’ry Oriental good speech is fundamental. / In France make a slight mistake; they regard you as a freak … (

Spoken:

) The French never care what you do, as long as you pronounce it properly.” The last verse also comes very close to its ultimate setting, with only three variations.

42

Lerner had started to move in the right direction with the number in the version contained in this copyist’s score. But he and Loewe then briefly changed track completely and shifted the focus of the number more onto national identity and less onto language. This third version of the song is the most surprising. Loewe took the first four pages (which contain the verse only) of the copyist’s score of the second version and appended to them a new six-page autograph. Following precedent, this contains the lyric in his hand and the music in a combination of his handwriting and Rittmann’s. On the front cover, Loewe crossed out the title and replaced it with “The English.”

43

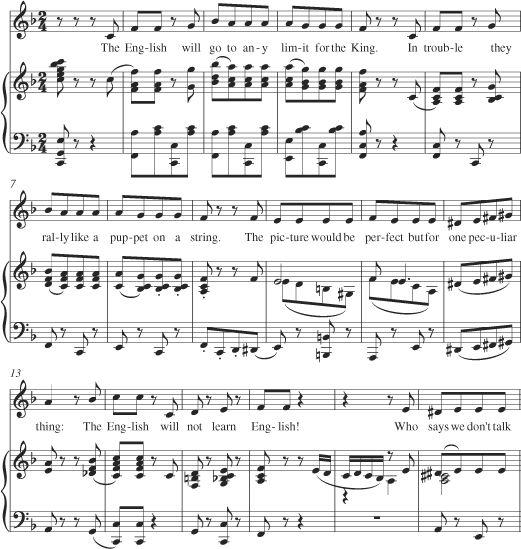

Here, Higgins rants about the way that the English “will go to any limit for the King,” “rally like a puppet on a string” and “fight without a whimper or a whine” but will not learn their language properly. Part of the refrain of the song is reproduced in

example 5.6

.

Ex. 5.6. “The English.”

Starting at bar 56, this version is almost completely different from the others, but it is inferior in most respects. The harmonically static first phrase is repeated note-for-note to form the second phrase; in itself, this is a redundant gesture. Bars 64–68 are more interesting, with minor-key inflections, but 72–80 are again repetitive and harmonically awkward. However, after a restatement of the opening material (80–95), from 96 to the first beat of bar 111 the music adopts almost the version that appears in the published score. The significant part is bars 102–111 (“The Scotch and Irish leave you close to tears”), in which both the music and lyric are practically in their final form for the first time.

44

This helps to place the song roughly between the production of the copyist’s score and Loewe’s autograph for the final version.