Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (25 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

Nevertheless, some ambiguities remain. The first lyric sheet (from Levin’s papers) consists of the refrain with just three deviations from the familiar version: “With one gigantic [instead of ‘enormous’] chair,” “Lots of fire [instead of ‘coal’],” and “Crept over the winder sill” instead of “Crept over me winder sill.”

5

The second lyric sheet (from the Warner-Chappell Collection) includes the verse and changes the refrain into its final version, with the

exception of “gigantic/enormous.”

6

Evidently this version was used to prepare the copyist’s score in the Warner-Chappell Collection. A copy intended for Bennett is annotated throughout to show how the basic score—containing the verse and one refrain in F major—was to be developed into the whole number with dance music. Bennett’s orchestral chart is almost entirely free of blemishes or corrections: the only real modification to the orchestration involves the removal of the bassoon and clarinet parts in bars 66–69 (“Lots of choc’late for me to eat…,” second refrain).

The copy of the song in the Loewe Collection, however, is confusing. It contains the verse and one refrain, with indications for two repeats of the refrain; there are also some crossed-out bars. This would seem to identify it as an early version of the song that was passed on to the copyist and orchestrator.

7

However, it is difficult to account for the fact that this supposedly “original” composer score uses almost the final version of the lyric: of the three instances of the “pre-improvement” lyric listed earlier, only “Crept over the winder sill” (as opposed to “over me”) is present here. None of this affects the authorship of the song, yet it suggests that this is not Loewe’s original manuscript but rather a fair copy for the use of others. This is the case with many of the piano-vocal scores in the composer’s handwriting held in the Loewe Collection that tend not to represent the actual pieces of paper on which the songs were first written. Like Richard Rodgers (more of whose sketches have survived), it seems that Loewe went about drafting his songs on a single stave before writing out a fuller piano-vocal score.

8

This serves as a reminder that placing too much importance on one source, instead of taking a larger sample and putting them into a wider context, can lead to a misunderstanding of the compositional process.

Even though “Wouldn’t it be Loverly?” has a simplicity that is appropriate for its dramatic context, it is nevertheless full of interesting features. The verse begins with four arpeggiated chords to punctuate Eliza’s delighted cries of “Aooow!” upon being given the money by Higgins: a seamless way for the music to segue out of the scene. This leads to the introduction, with its lazily descending melodic turns. But Loewe cuts it short with a perfect cadence as the men break into their “Quasi recitativo”

a cappella

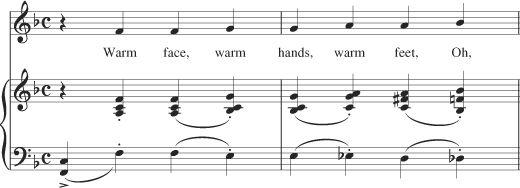

verse, in which they describe their dreams. The “false” introduction then returns and drives into Eliza’s F-major refrain. The latter’s outward cockney charm belies its complex harmonization and chromaticism. For instance, bar 21 (“room somewhere”) moves into the subdominant area, establishing the song’s warmth, but although bar 23 (“cold night air”) ends on the expected dominant-seventh chord, it does so via an abrupt G-major seventh at the start of the bar. Perhaps the most elegant feature is the use of contrary motion in bars 24–25

(“With one enormous chair”), whose appoggiaturas come into their own when the pattern recurs in 27–28 to accent the repetition in the phrase “Warm face, warm hands, warm feet” (

ex. 5.1

). The bridge section (“Oh, so loverly sittin’ absobloomin’lutely still”) also has a fast harmonic rhythm, again featuring examples of chromatic voice-leading, while the final section is extended beyond its expected eight bars because of a prolongation of the title phrase. The second refrain features four-part choral writing alongside Eliza’s line, followed by a brief dance section in A-flat major in which the men whistle the melody. The number ends as Eliza sings a final “Oh, wouldn’t it be loverly?” to which the men respond by repeating the final word. What Loewe achieves in this song is an introduction to Eliza’s softer side and the camaraderie of the Covent Garden workers while maintaining a richness of texture. Lerner’s idiomatic lyric plays its part in establishing the social class of the characters, but so too does Loewe’s melody. Its harmonization, however, is comparatively ornate, taking the song far beyond its broad allusion to the jauntiness of the English musical hall.

The same goes for “Just You Wait,” Eliza’s next song. It features a strong martial aspect, depicting Eliza’s fury at Higgins’s sadistic treatment of her, and the freedom of form Loewe uses in the number is equally striking. After the opening refrain in C minor, Loewe writes an episode in D-flat major in which Eliza dreams of fame and fortune. She imagines gaining the king’s attention and requesting that Higgins be beheaded. A transition in B-flat major (“‘Done,’ says the King…”) leads back into the opening material. This time it is rendered in C major, and the music portrays Higgins’s march to the firing line (“Then they’ll march you, ’enry ’iggins, to the wall”). Therefore, while the opening passage has the overall trappings of the 32-bar song (abbreviated to 30 due to the melodic diminution of the return of the A section at the end), the number as a whole also follows a similar form in macrocosm, namely a long opening section in which the character lays out her position, a

contrasting section about three-quarters of the way through, and a return to the opening material. Also, in spite of its modal contrast to the opening section, the D-flat major passage retains its links to the main “Just you wait” theme by starting each phrase with a similar three-note ascending pick-up (“One day,” “One eve[ning],” “All the peo[ple]” and so on). Along with the ominously understated fermatas when Eliza declares she wants Higgins’s head and the jubilant trumpet line when the king gives his order, this is one of several aspects of the number that show how Lerner and Loewe make even a short song into a complex musical scene.

Ex. 5.1. “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” bars 27–28.

Lerner states that “Just You Wait” was one of the first songs he tackled with Loewe, and names it as one of those that he played for Mary Martin during their first meeting about the show.

9

This is supported by Outline 1 (chap. 3), in which “Just You Wait” is one of the few songs referred to by title; Eliza sings it in the upstairs bathroom, “wet and shaking like a drowned rat.” By Outline 3, a montage of lessons has been introduced, but the song is not explicitly referred to. Only Outline 4 confirms its final position: it takes place in Higgins’s study and is the “Second Song” after a first “Song: Montage of lessons” (surely “The Servants’ Chorus”). At this stage “Just You Wait” was to be preceded by a refrain of “The Servants’ Chorus,” but in the published show Eliza’s song comes first, allowing her to vent her frustration before the servants illustrate the passage of time during the lessons. The rehearsal script shows an intermediate structure: “Just You Wait” is immediately followed by a blackout, a verse of the servants’ song, another blackout, then the lesson about “The rain in Spain.” The published script, however, misses out this instance of the “Chorus” and goes straight to the lesson.

This illustrates how Lerner and Loewe operated on both the local and the broader level. Originally, the song allowed Eliza to express her humiliation at being stripped of her clothes, forced to have a bath, and compelled to wear Higgins’s bathrobe. But by changing it to express Eliza’s frustration about her lessons rather than about being treated inhumanely, Lerner softened the dislikeable part of Higgins’s personality. “Just You Wait” isolates the tension between the two so that it tells of a discouraged pupil who does not know how to fulfill the expectations of a perturbed teacher, who in turn does not know how to give his student what she needs. Language, not misogyny, is the subject of the song, even though the lyric is outwardly a hyperbolic description of Eliza’s imagined retribution.

The lyric underwent one major change and one minor alteration. The major change involved the complete recasting of the third and fourth verses, which were originally as follows:

Oooooo …’enry ’iggins!

Have your fun but ’enry ’iggins you beware.

Ooooo …’enry ’iggins!

When the shoe is on the other foot, take care!

You won’t think it such a farce

When I kick your bloomin’ arse!

This version appears on a lyric sheet in Levin’s papers and is also used in a copyist’s score held in the Warner-Chappell Collection.

10

These sources also contain a small alteration in the lyric of the penultimate stanza of the song (the king’s imaginary lines): “All the people will celebrate all over the land; / And whatever you wish and want will be my command.” was modified to “All the people will celebrate the glory of you, / And whatever you wish and want I gladly will do.” Though the big change was made in the rehearsal script and Bennett’s orchestration, both contain the king’s couplet in its original form.

However, the composer’s manuscript is again difficult to place. It is certainly not Loewe’s “original” score for the number, because Rittmann’s hand is unmistakable in the writing of the clefs, time and key signatures, and most of the piano part. Loewe wrote out the lyric, vocal line, and tempo markings, but since Rittmann did not join the team until late 1955 (whereas we know the song was conceived much earlier), the manuscript must be a fair copy prepared for the copyist and orchestrator. On the title page, Loewe wrote “Att. Franz [Allers, the conductor]: Julie may be E flat? Please try.” The copyist’s score follows Loewe in every respect including the use of the key of D minor and does not make this transposition, but a note at the top reads: “1 tone lower.” Since this score was intended for Bennett’s use, it is no surprise that the orchestrator’s full score is in the published key of C minor.

11

It is curious that Loewe’s score contains the final version of the lyric throughout—unlike the original lyric used in the copyist’s score, which was undoubtedly created from Loewe’s manuscript—but there is some smudging around the lyric for the third stanza, suggesting a possible later amendment. In all other respects, the sources indicate very little in the way of musical changes to the song as time went on.

The next number was much slower in coming. As noted previously, the song originally intended to fill the spot after “The Rain in Spain” was called “Shy.” A solo for Eliza, it speaks overtly of the character’s love for Higgins and was certainly in place by the early autumn of 1955. On Outline 4, it is named as both the “Third Song” of act 1, scene 5, and the piece of music intended to end the musical. It was eventually replaced, of course, by “I Could Have

Danced All Night.” A musical synopsis of the second act of the show, kept in an envelope in the Warner-Chappell Collection, refers to the reprise of a song for Eliza called “The Story of My Life,” which is crossed out and replaced by “I Could Have Danced” in Loewe’s hand; presumably this was an intermediate replacement for “Shy” before “Danced” was composed.

12

Lerner admits the problems the collaborators had with this song in his autobiography. He says they had tried to give Eliza “a lyrical burst of triumph” after “The Rain in Spain,” which would also reveal “her unconscious feelings for Higgins.” But all their attempts “emerged with her true feelings on her sleeve.”

13

Lerner goes on to explain how he managed to come up with the title of “I Could Have Danced All Night” during the final week before the start of rehearsals.

14

He says that “Fritz set it in a day” and that he finished writing the words in twenty-four hours—“but not to my satisfaction.” He admired Loewe’s melody, but “blushed” when singing him the line: “‘And [

sic

] all at once my heart took flight’. I promised Fritz I would change it as soon as I could. As it turned out, I was never able to.”

15

None of this confirms Marni Nixon’s claim that she first heard the song in “the early spring of 1954,” when it “was in 3/4 time with a very European operetta sound,”

16

but it is true that the title of the song was at one point “I Want to Dance All Night.” Curiously, this was an afterthought rather than the original version. The rehearsal script, Loewe’s autograph, and Bennett’s full score all use the words “I Could Have Danced” as does a copyist’s score in Levin’s papers.

17

However, a photocopy of this copyist’s score is headed “I Want to Dance All Night” in Loewe’s hand,

18

and another typed script in Levin’s papers replaces “Could” with “Want” in the final scene (where “I Want to Dance” is heard in the orchestra).

19

A further script also has this, and on both the list of musical numbers and the pages of the actual song (1-5-52 to 1-5-55) the title is shown as “I Want to Dance All Night.”

20

Strangely, the lyric itself still reads “I could have danced.” The playbills for the tryouts in New Haven and Philadelphia use the word “Want,” as did early pressings of the show’s Original Cast Album (though Julie Andrews sings “could” throughout).

21

It seems that Lerner briefly considered a change but finally decided to leave the lyric alone.

22