Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (20 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

The next song also contains material that was subsequently reused. In his first memoir, Rex Harrison says that when Lerner and Loewe first came to talk to him about doing the show, “There was a number called ‘Lady Liza’, a very pushy sort of Broadway tune which Fritz later turned into a waltz and

used in the ballroom scene.”

11

Curiously, in his second autobiography, the actor contradicts himself and says that the song “was skillfully turned into ‘The Ascot Gavotte,’” but he was correct the first time.

12

As with “Please Don’t Marry Me,” the intended context of “Lady Liza” is apparent from Outlines 1 and 2 (see chap. 3). After Eliza’s debacle at Ascot, Higgins and Pickering discover her crying on a park bench, convinced she cannot succeed. But “the men persuade her she can. They do it in a song, which they sing together to her: ‘Lady Liza.’”

13

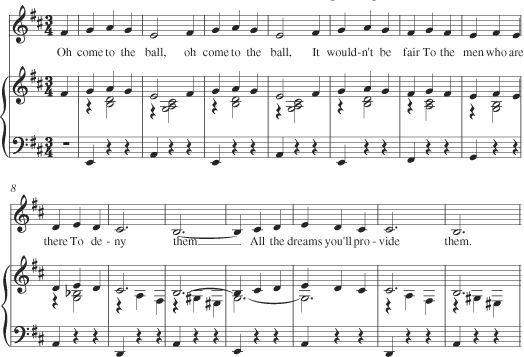

Ex. 4.5. “Lady Liza.”

The manuscript for the song is in two parts. On the front cover is the melody, with “Higgins/Pickering” marked to the left of the title. Inside the folded manuscript is another title, “Liza—Counter,” while on two bracketed systems are the same Higgins/Pickering melody plus a counterpoint for “Jane” and “Math,” presumably the maids. The start of this combined version of the piece is shown in

example 4.5

. As Harrison says, the melody of the first four bars was transformed into the beginning of “The Embassy Waltz,” but the rest of it is different. The version of the song with the counterpoint was probably intended for a reprise after Ascot mentioned in Outlines 1 and 2, to conclude Eliza’s second series of lessons (“At the end of the sequence Liza is doing everything beautifully and the chorus sings, ‘Lady Liza’”).

14

Although the melody is unremarkable and the lyric full of clichés—such as “gray above once again blue”—the servants’ counterpoint is notable for its wit. “Is it malaria? Or something scarier?” they ask, on seeing Eliza, Higgins,

and Pickering jubilant after her transformation. In essence, this reaction was eventually replaced by two earlier reactions: first, Mrs. Pearce’s lines after she has been awoken by the pounding noise made by the trio when they sing “The Rain in Spain” (“Are you feeling all right, Mr. Higgins?”); and second, the maids’ interjections in Eliza’s “I Could Have Danced All Night” which similarly provide a contrasting viewpoint on the main theme being heard (“You’re up too late, miss, / And sure as fate, miss, / You’ll catch a cold”). In the published show, of course, this material is shown before the Ascot scene rather than after it, because the final part of Eliza’s transformation happens offstage and we see only the result, not the process. The words for the remaining verses of the song are provided in the collection of lyrics in Levin’s papers. This lyric sheet shows that the last line of every verse is changed from the indefinite to the personal article: “You’ll be a lady” becomes “You’ll be my lady” in the first two verses and “One day my lady will Liza be!” in the final one. This is yet another example of the far more explicit positing of Higgins as Eliza’s lover in Lerner and Loewe’s early ideas for the show.

Like “Please Don’t Marry Me” and “There’s a Thing Called Love,” “Lady Liza” was probably dropped from the score because it simply does not fit either the style of the piece or the characterization of the main protagonists as they were ultimately evolved. These three manuscripts provide us with a window into the composer’s workshop, showing how Loewe dealt with both microlevel details such as word-setting and macrolevel issues such as refitting a melody with a new lyric or developing a musical style for a character.

In all probability, the three songs discussed in the previous section were “fully composed” in the sense that we can assume Loewe must have played them with accompaniments rather than just the melodies: Lerner reports that Loewe always composed complete songs at the piano with the lyricist in the room, and that he paid attention to the harmonic and accompaniment material.

15

But only one unused song in the Loewe and Warner-Chappell Collections exists in a completely written out piano-vocal score: “Shy.” It is mentioned by Julie Andrews in her autobiography as “a very pretty song,” and she adds that “originally Eliza sang it to show her feelings for Higgins. Alan Lerner realized that in Shaw’s original play, the main characters never once speak of love. Therefore, he and Fritz created another song, the famous ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’, which conveys all the affection and emotion Eliza feels, yet never once mentions the word.”

16

Andrews’s explanation of the position of the song in the show is corroborated by Outline 4 (see chap. 3), which has “Shy” at the end of the montage of lessons instead of “I Could Have Danced.”

17

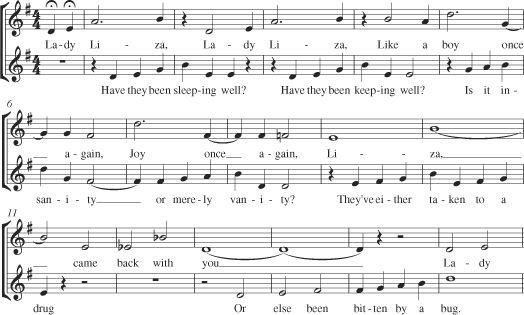

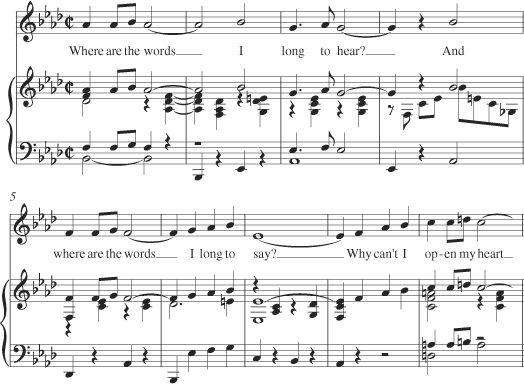

Two manuscripts of the song exist. The first is entirely in Loewe’s hand, with the complete lyric, on three sides of the standard Chappell manuscript paper that the composer used for most of his work; there are no dynamic or expressive markings. The second document is the work of two separate parties, and the accompaniment is completely different in style.

18

The melody, title, and lyric are in Loewe’s handwriting, but the clefs, key signatures, piano lines, cover title, tempo, and expressive markings are all in the hand of Trude Rittmann, the dance arranger. Of course, this does not necessarily prove divided authorship—especially since years later Rittmann confirmed that Loewe did not like to write things down but

was

concerned to have overall control of his scores—but it is striking that the accompaniment for Rittmann’s version is much more fluent than Loewe’s original.

19

The beginning of both versions is reproduced in

examples 4.6

and

4.7

.

Musically the song is particularly interesting for its employment of harmonically complex (and sometimes ambiguous) maneuvers. The tonic chord does not appear unmodified in root position until the final two bars, for example, and the song both launches on a surprising seventh chord (though there might have been an introduction, had the song made it into the show) and avoids sounding the tonic at various points where it could be expected. The minor seventh at the beginning of bar 9 is typical of Loewe’s ability to

create an unforeseen harmonization of a straightforward melody; he sidesteps harmonic stability. Similarly, the accompaniment flows strongly for the first two phrases and breaks at bar 8 before continuing again in a similar vein. At bars 14–16 (not shown) Loewe employs a stepwise resolution of a strong dissonance over a vocal pedal note which is not unlike his treatment of the words “I only know [when he began to dance with me]” from “I Could Have Danced All Night”—ironically so, given that this song replaced “Shy.” In both cases, the momentum of the music is stopped while the ensuing section restarts with three emphatic chords that each harmonize the repeated melody note in a different way, giving dramatic release. The two songs also share another similarity in terms of lyrics: “Why can’t I open my heart and let them fly?” (“Shy”) is not unlike “Why all at once my heart took flight” (“I Could Have Danced”). Amusingly, the latter line is the subject of a piece of self-criticism in Lerner’s autobiography.

20

Ex. 4.6. “Shy,” Loewe version.

Ex. 4.7. “Shy,” Loewe-Rittmann version.

Exactly why a second accompaniment was written for “Shy” is unknown, but it may be because, as Andrews implies, a sentimental love song was incoherent in light of the unspoken affection between Higgins and Eliza. Perhaps before discarding Lerner’s lyric, which is indeed overt in its expression of love, Loewe either decided to refit the music in a new character, or he commissioned Rittmann to do so. It is clear even in the first bar

of the “new” version that the melody is now matched with a beguine accompaniment, which to an extent numbs the triteness of the lyric. At the same time, the liveliness of the new accompaniment rhythms does not cohere well with the open sincerity of the words. It is little wonder, therefore, that “Shy” was not used. Even had the material been top-drawer Lerner and Loewe, the flagrant admission that Eliza is in love with Higgins is out of place in a musical where romance simmers only quietly in the background.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the show’s genesis is the sequence of numbers that originally bridged the gap between Ascot and the Embassy Ball but was later replaced by a short passage of dialogue. All sources agree that the first act of the musical was too long during its first performance in New Haven, motivating Lerner, Loewe and Moss Hart to remove “Come to the Ball,” the “Dress Ballet” and “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight” and thereby excise roughly fifteen minutes from the running time.

21

The three cut numbers are at once familiar and unknown. They were performed in New Haven, “Come to the Ball” was recorded, and “Say a Prayer For Me Tonight” was reused in the film of

Gigi

. But many of the sources related to these numbers have not previously been examined or written about, and the “Dress Ballet” is especially obscure. The rest of this chapter pieces together archival material to present an appraisal of this cut scene, which was originally planned to be among the show’s highlights.

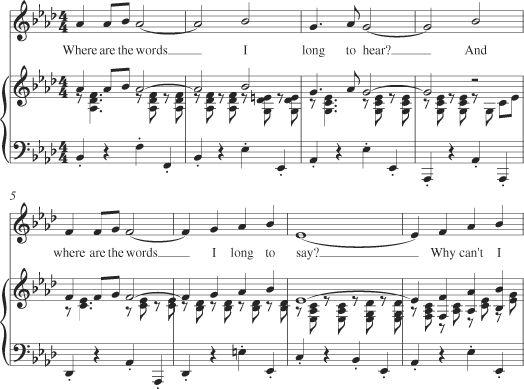

According to Lerner, “Come to the Ball” (see

ex. 4.8

) was intended to be Harrison’s

pièce de résistance

, but after its first performance the lyricist deemed it “a disaster in three-quarter time.”

22

The piece exists in several different versions: (1) Loewe’s autograph, which is in E major, contains only the first refrain and is very simply harmonized; (2) a copyist’s vocal score in D major (the final key) from the Loewe Collection, lightly annotated by the composer and representing an intermediate version of the song, with different transition music between the second refrain and interlude, and a different ending; and (3) a modified version of the same copyist’s score, the conductor’s short score, and the orchestrator’s autograph full score, all of which come from the Warner-Chappell Collection and represent the definitive version.

23

Ex. 4.8. “Come to the Ball,” beginning.