Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (18 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

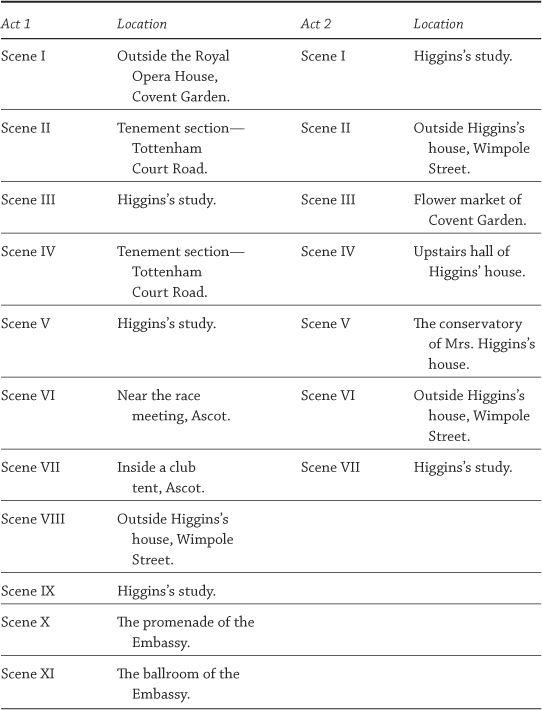

Dualities are also used cleverly in the scenic structure of the piece. Act 1, scenes 6/7 (Ascot) and 10/11 (the Embassy Ball) are connected in being two pairs of scenes that take place in high society where Eliza is put to the test. In both cases the first of each pair takes place outside the main location and involves a discussion between Pickering and Mrs. Higgins about Eliza and the potential for disaster in the following scene. The second scene of each pair is the actual event—the first goes badly (Ascot), the second is a triumph (the ball). In this way Lerner cleverly replicates the format used in the Ascot scene to rebuild the tension for the Embassy Ball scene, thereby making us believe that Eliza could fail again (something that is intensified by the presence of

Zoltan Karpathy, who threatens to reveal Eliza’s background). The two remaining locations also occur in pairs. The “Tenement section” at Tottenham Court Road in act 1, scenes 2 and 4, is the place where we meet Alfred Doolittle and where he sings both the original rendition and reprise of “With a Little Bit of Luck,” while the space outside Higgins’s house on Wimpole Street is the location for Freddy’s “On the Street Where You Live” (act 1, scene

7) and its reprise (act 2, scene 2). In both instances, we return to both a location and a song that has been heard before but experience them in a completely new light. When Doolittle’s song about optimism is reprised, it comes after the news of Eliza’s departure to live with Higgins, which represents a possible source of money for Doolittle. Similarly, the reprise of “On the Street” finds an “undaunted” Freddy (

PS

, 115) still singing his song in vain, but we see it in a new light when Eliza rejects his bland vision of romance and spits out the fiery “Show Me.”

Table 3.6.

Scenic Outline of

My Fair Lady

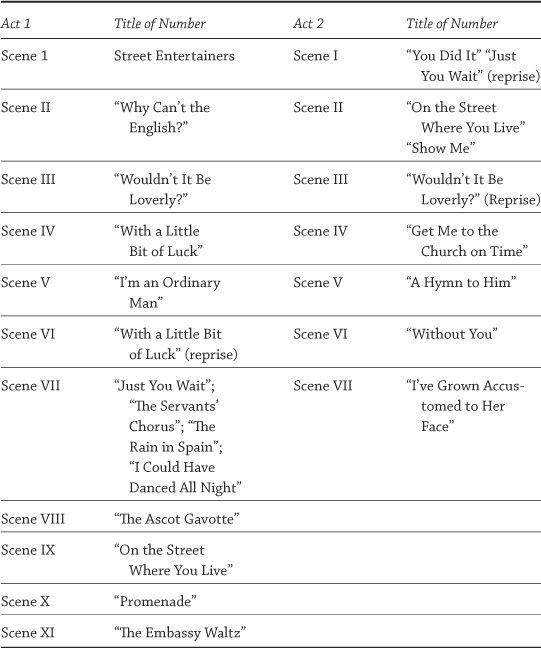

Strongly tied to this careful distribution of the scene locations is the musical structure of the piece (see

table 3.7

). Unquestionably, certain conventions determine the allocation of the numbers between the two acts, but it is striking that many of the songs from the first act either reappear or have some sort of analogue in the second act. There are several examples in addition to those discussed earlier. When Eliza hears the reprise of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” sung around a fire by the vegetable costermongers in act 2, it is no longer her theme, and it serves to tell her that she no longer belongs in the market. The return of “Just You Wait” has a similar function, because a song that Eliza originally sang in her Cockney accent is now sung in her refined accent, reminding her—and us—that she is no longer the person she was. It also takes on a sad irony, because the threats Eliza originally throws at the imaginary Higgins when the song first appears in act 1 are now shown to be completely empty, since he has just stormed off, leaving her crouching on the floor in tears (

PS

, 113–4).

48

In its original version, this song also shares something with “Show Me” and “Without You,” two numbers that have different styles but communicate Eliza’s feisty anger against men.

The trend continues with “I’m an Ordinary Man,” which is strongly connected to “A Hymn to Him” in subject matter and style, since both deal with Higgins’s attitudes to gender relations. Even though “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” has little explicit connection to the first act except for the brief reference to “I’m an Ordinary Man,” we will see in

chapter 5

how it contains material from the cut first-act song “Come to the Ball” and reverses the meaning of the lyric from praise to insult. This theme was also used in the cut ballet from act 1. So even if “Accustomed” was planned as a bigger summation of themes than it is in the published score, it still provides an accumulative finale to the show. In addition to its own reprise, “With a Little Bit of Luck” is obviously connected to “Get Me to the Church on Time” as a similar music hall–style song for Doolittle. There is also an irony in the fact that Doolittle’s mocking rebuttal of marriage and responsibility in “Luck” has now been turned on his head as his friends bid him a poignant farewell on his wedding day. Finally, “You Did It” is briefly brought back later in act 2, when Higgins

interrupts Eliza’s “Without You” with a short verse of “By George, I really did it.” Even this brief summary of the musical contents of the show demonstrates how strongly planned the material is.

Table 3.7.

Outline of Musical Numbers in

My Fair Lady

While not every number can or should be seen as functioning as part of a broader duality, there are other important aspects to the show’s musical structure. In particular, both acts have a sequence of musical numbers that increase dramatic tension over a self-contained unit of time. In act 1, this happens in the fifth scene, where four musical numbers take Eliza on a

journey from frustration to elation. “Just You Wait” is closely followed by the sequence of lessons that are interspersed with verses of “The Servants’ Chorus.” The last of these leads into the final lesson, in which Higgins teaches Eliza to pronounce “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain” correctly. In turn, this leads into the jubilant song, “The Rain in Spain,” followed by the even more elated “I Could Have Danced All Night.” This last song is the close of the sequence, which occurs over the course of a single scene and provides one of the most imaginative and effective parts of the show.

49

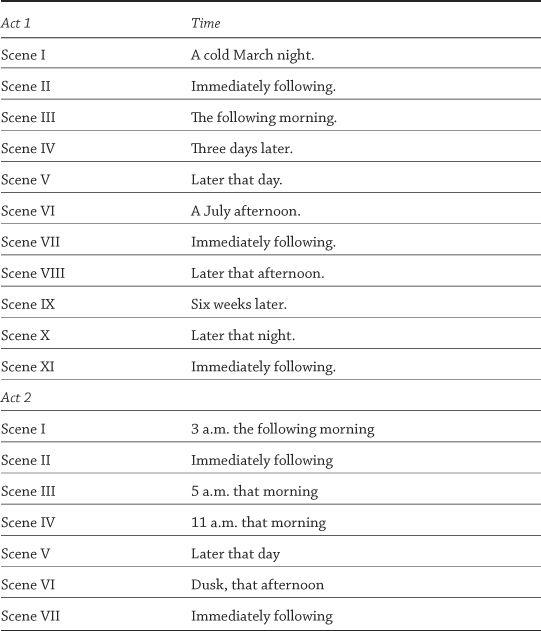

Table 3.8.

Outline of Timescale of Scenes in

My Fair Lady

The example from the second act is arguably even more special. After the concerted number “You Did It” at the opening of the act, the long scene of dialogue between Eliza and Higgins that ensues is closed by Eliza’s tearful reprise of “Just You Wait.” This initiates an unbroken chain of music also encompassing the reprise of “On the Street,” Eliza’s new song “Show Me,” and the reprise of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” in the flower market. Even though it lasts only seven or eight minutes, this sequence of music provides just the kick that most musicals need in the middle of their second acts. The tension mounts during the first two reprises and reaches its highpoint in “Show Me,” where Eliza vents her anger as never before. The vigor of this number is cleverly reduced by the “Flower Market” music, which depicts early morning at Covent Garden and segues into the gentle reprise of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” This complex chain of numbers is a prime example of how Lerner and Loewe’s adaptation of

Pygmalion

adds an expressive dimension not found in the play.

Their third structural tool is the manipulation of time.

Table 3.8

shows how the musical’s timescale is specifically defined in terms of month and time of the day. Interestingly, this is in contrast to the published version of Shaw’s stage play, which is comparatively vague regarding time and date (see

table 3.9

).

50

In light of this, Lerner’s structure is especially well conceived, with the show working in three discreet periods of time. The first act is in three sequences: the meeting of Eliza and Higgins and their initial lessons during March (scenes 1–5); Ascot in July (scenes 6–8); and the Embassy Ball in late August/early September (scenes 9-11). This provides a three-part exposition in which the establishment of the bet and its early consequences (the Ascot and Embassy scenes) are depicted, leaving the second act in which to discuss the resolution of Higgins’s and Eliza’s problematic relationship. That makes the timescale of the second act all the more important: it takes place over the course of a single day and follows on directly from the end of act 1, with

scenes at 3 a.m., 5 a.m., 11 a.m., during the afternoon, and at dusk. Obviously, there is a dramatic push to this format, whereby the scenes almost occur in real time and provide a sense of continuity. By setting the action against this “cycle of the hours,” Lerner ensured that the second act had just as much momentum—if not more—than the first. It is also ingenious that the day of the ball and the immediate aftermath straddles the intermission, thereby providing a “cliff-hanger” about whether the experiment has been successful—another sign of the master of the theater at work.

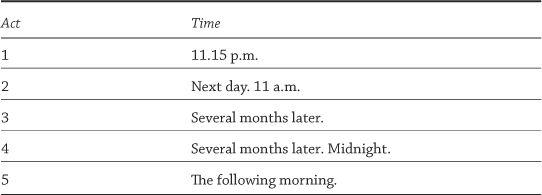

Table 3.9.

Outline of Timescale of Acts in

Pygmalion

KNOWING THE SCORE

The fact that the likes of Rodgers and Hammerstein abandoned their adaptation of

Pygmalion

makes Lerner and Loewe’s achievement in

My Fair Lady

all the more impressive. This was a show that confounded even the very best, partly because of the multifaceted challenge of writing a musical based on this particular play. Just as the evolution of Lerner’s script involved a shift of focus from Shaw’s determinedly unromantic view of the Higgins-Eliza relationship to something more ambiguous for the musical, a change of gesture also had to be carried through in the score. This created a semiotic problem for the composer: how to avoid writing standard types of Broadway songs but remain within the recognized bounds of the Broadway musical. Yet one of Loewe’s gifts as a composer was his ability to adopt a wide range of styles. Nor was this limited to broad stylistic gestures such as the “Celtic” music in

Brigadoon

or hints of the Wild West in

Paint Your Wagon

: Loewe’s musicals are written with a fine brush, allowing him to conjure up place, character, and mood within the space of a single song.

This is especially true of

My Fair Lady

. But in order to discuss the show’s score, it is essential first to understand the nature of the material available. Although studies of musicals typically use published piano reductions of orchestral scores as the basis for their analyses, these commercially available scores usually represent only a retrospective snapshot of what was performed on Broadway. Rarely are all the expressive aspects of a performance represented, nor is the complexity of the compositional process normally clear from a homogenized score. Typically, the composer would write either a simple piano-vocal score or a lead sheet with chord symbols (or even just create the piece at the keyboard in the case of composers who could not

notate music). This would then be adapted and expanded by an arranger according to factors such as the number of verses that appeared in the final script or the need for dance music, before the orchestrators fleshed out the material and expanded the texture for a full complement of instruments. At best, published vocal scores might partly be based on the composer’s initial manuscripts, but taken as a whole they are normally extrapolated from either the full score or the conductor’s short score after the event, and therefore bear a comparatively remote relationship to the stage performances.