Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (19 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

In the case of

My Fair Lady

, the musical artifacts (mostly derived from the Frederick Loewe and Warner-Chappell Collections at the Library of Congress) can be divided into the following categories:

• Untitled melodic sketches in Loewe’s hand, without lyrics, which can be identified as now-familiar songs;

• Completed melodies in Loewe’s hand, without accompaniment, which may or may not have lyrics attached and may not ultimately have made it into the finished show;

• Completed piano-vocal scores wholly or partly in Loewe’s hand for both familiar and cut songs; the verses may be absent or only one verse may appear, compared to multiple verses in the published vocal score;

• Vocal and choral scores of intermediate and final versions of some of the songs in unknown copyists’ hands;

• Piano scores (some of them representing intermediate versions) of dance music, incidental music, vocal reprises, and instrumental numbers in the handwriting of Trude Rittmann, the dance arranger;

• Full orchestral scores in the hands of the credited orchestrators, Robert Russell Bennett and Philip J Lang, as well as the ghost orchestrator, Jack Mason;

• Instrumental performing parts and conductor’s short scores in unknown copyists’ hands;

• Two editions of the published vocal score: the original, edited by the show’s conductor, Franz Allers (1956), and a corrected revision (1969).

In addition, lyric sheets containing versions of the texts of the songs not documented elsewhere are discussed where relevant. These come from two sources: a folder in Herman Levin’s papers, and an envelope marked “Franz Allers Lyrics” hidden in the middle of a pile of instrumental parts for the show in the Warner-Chappell Collection.

No song or number is represented by a source or sources from all of these categories, nor should it be assumed that there ever were documents for each song in every category. For instance, songs such as “I Could Have Danced All

Night” were created late in the compositional process and were probably written down as relatively complete numbers first time around, so there might never have been a simple melodic sketch. Others never made it past the drafting stage and were never orchestrated. In at least one case, a score has been mislaid or separated from the collection: “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight” was performed during the initial New Haven out-of-town tryouts and then cut, but although a copyist’s score and the full score have survived in the Warner-Chappell Collection, there is no autograph piano-vocal score for the song in the Loewe Collection. Nonetheless, the documents as a whole give a vivid overview of the process of creating the score of

Fair Lady

as a “performance” for Broadway.

The manuscripts of the songs discussed in this section all derive from the Frederick Loewe Collection. Some of them are fully completed songs that could be performed, while others are in the form of melodic outlines and, interesting though they are, reveal little information other than the shape of the melody. There are six melodic sketches with titles but no lyrics that are known to have been intended for the show. Two of them, “What is a Woman?” and “Who is the Lady?,” are almost identical and are probably different attempts to write some kind of song for Henry Higgins; “Dear Little Fool” is headed “Higgins” and is therefore presumed to be for the same character; “Over Your Head” was the original version of Eliza’s “Show Me”; and “Limehouse” and “The Undeserving Poor” were planned for the original opening scenes of the show, the latter intended for Doolittle.

1

“Dear Little Fool” is a simple melody in E-flat major with very few accidentals or chromatic inflections; its many long, sustained notes suggest that it was an attempt at a love song of the kind that Higgins does not sing in the finished show. It is difficult to tell whether “Limehouse” was intended as a solo or choral number, and indeed what its message might have been. However, there is some chromatic movement in the melody, which was probably an attempt to evoke the Chinese atmosphere of the projected opening scene at Limehouse in Outline 1 (see

table 3.1

). Similarly, the melody of “The Undeserving Poor” is simple, and since it was intended for Doolittle and his cronies it is probably reasonable to assume that it might have made a rousing song of the same ilk as “Get Me to the Church on Time” and “With a Little Bit of Luck.”

In addition to these songs with a documented connection to

Fair Lady

, there are a few other manuscripts in the Loewe Collection, which may also be related to it. The title of “What’s To Become of Me?” mirrors so closely Eliza’s tortured speech after the ball—“Where am I to go? What am I to do? What’s to become

of me?”—that it is highly probable that it was a song for this position in the show.

2

Underneath the short melody is a note, “There’s Always One,” which probably refers to another sketch, “There’s Always One You Can’t Forget.”

3

The latter is characterized by dotted rhythms and melodic leaps, but again it is difficult to infer much information from it; the same goes for “Say Hello For Me,” which is on the reverse of “What’s to Become of Me?” and has only a brief melodic sketch and a few chords to indicate a possible accompaniment pattern at the bottom. There is also another page of sketches for “What’s to Become of Me?,” the first four bars of which contain an outline harmonization.

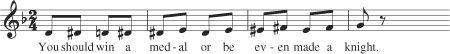

Fascinating though these manuscripts are, they tell us only a little about the finished songs or the composer and lyricist’s intentions for the characters who were to sing them. Nevertheless, some observations can be made. In the extract of “What Is a Woman?” in

example 4.1

,

4

for instance, we can see that part of the melody is familiar from a song that eventually made it into the show: bars 17–19 (and the similar patterns in 21–22 and 25–27) resemble the melodic line of Pickering’s words “You should get a medal, / Or be even made a knight” in the second-act opener, “You Did It” (

ex. 4.2

). On this evidence alone, the resemblance seems curious rather than significant. All it really tells us is that when Loewe had created music that was not ultimately put to use, he thought nothing of recycling it later in a different form—a reminder of how little, sometimes, the melody of a song is bound in meaning to its lyric.

More obviously illuminating are three draft melodies with both titles and lyrics, known as “lead sheets.” This time, the function, meaning, and content of all three is far more obvious here, though Loewe’s exact harmonization is unknown. Lerner sheds light on one of the songs in

The Street Where I Live

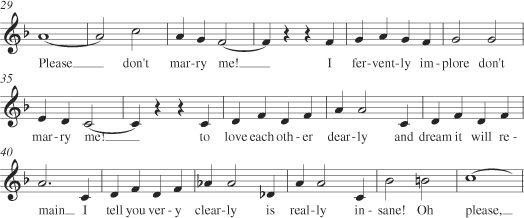

: “Our first attempt to dramatize Higgins’ misogyny resulted in a song called ‘Please Don’t Marry Me.’”

5

The song was the precursor to “I’m an Ordinary Man,” but with a slightly different context (see Outlines 1 and 2 in chap. 3). The original version of the scene had Higgins responding negatively to the suggestion that he should marry someone far from his liking, so the title “Please Don’t Marry Me” referred specifically to Miss Eynsford Hill as well as

being Higgins’s general

credo

(see

ex. 4.3

).

6

By contrast, the replacement, “I’m an Ordinary Man,” comes in response to Pickering’s question, “Are you a man of good character where women are concerned?”

7

The focus in this song is on the perceived consequences of the repeated line, “Let a woman in your life”; although marriage is mentioned briefly, the lyric is more about relationships between men and women in general than Eliza specifically. In addition to this lead sheet, a lyric sheet in Herman Levin’s papers contains the words to the second refrain, suggesting that the song was fully worked upon before Lerner and Loewe discarded it.

8

Ex. 4.1. Extract from a melody “What Is a Woman?”

Ex. 4.2. Extract from “You Did It.”

Ex. 4.3. Extract from the refrain of Higgins’s “Please Don’t Marry Me.”

The verse (not included in

ex. 4.3

) shows Loewe’s freedom of form: after the simple lines of the first eight bars, the time signature briefly changes to 6/8 while he quotes the traditional song “Drink To Me Only With Thine Eyes,” the romantic lyric of which Higgins mocks (“I hate that optical brew”). But again, the song is of interest because it contains material, which would later become familiar in another context. The melody in bars 36–43 is similar to that of bars 8–16 of the song “What Do the Simple Folk Do?” from

Camelot

(1960), as shown in

example 4.4

. The wittiness of some of the lyric writing is not entirely foreign to the way the Professor’s character was ultimately sketched, for instance the couplet: “That someday you’d abhor me would torture me with fears, / But having you adore me would bore me to tears.” But given the upbeat, comic character of the lyric, it seems likely that the accompaniment was quite jolly and that the tempo was fast, making “Please Don’t

Marry Me” a glossy Broadway number that would have been incoherent with Higgins’s other songs.

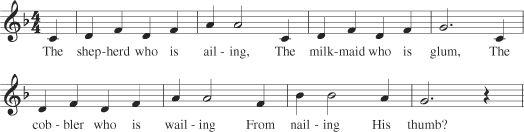

Ex. 4.4. Extract from “What Do the Simple Folk Do?” from

Camelot.

Similarly, the next unused song, “There’s a Thing Called Love,” is uncharacteristic of Eliza’s completed numbers. The lyric alone tells us that this is a typical love song:

There’s a thing called love

In the twinkling of an eye you know the meaning of.

There’s a thing called love—

By the count of one

The lovely deed is done!

A precious thing called love—

When it’s yours you know how much it’s worth.

You can tell despair

Farewell, despair,

Love came in time,

And made me glad that I’m

On earth!

9

The number was probably intended for the position later taken by “I Could Have Danced All Night.” Eliza’s sentiments make sense in the context of having succeeded in pronouncing “The Rain in Spain” correctly and gained a new warmth from Higgins, with whom she now fancies herself to be in love.

10

Again, such an expression of love was probably too overt for Lerner’s overall plan for the show, so it is not surprising that it was cut. However, the melody later resurfaced as “In this Wide, Wide, World” in the 1973 stage version of

Gigi

.