Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (6 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

Meanwhile, Lerner—ever the insatiable workaholic—had begun work on new projects with Arthur Schwartz. On March 17, 1953, the

New York Times

reported that the pair had “reached an agreement with Al Capp to make a musical of his popular cartoon,

Li’l Abner

, for presentation on Broadway next season. … Mr. Schwartz will compose the music and Mr. Lerner will work out the book and lyrics. Together, they will serve as producers of the venture.”

55

The article went on to relate how the idea of making a musical out of Capp’s cartoons had previously been explored by Joshua Logan, the director of

South Pacific

, and that this would mark the first collaboration between Lerner and Schwartz, who had been a prolific writer of songs for Broadway for more than twenty years.

56

The article also reported that Lerner was writing another play for Schwartz, and that the pair was working on a film adaptation of Lerner and Loewe’s 1951 stage show

Paint Your Wagon

—clear confirmation of a rift between the original collaborators, with three projects outlined for the new Lerner-Schwartz combination. Their

Wagon

film had been mentioned in the

New York Times

as early as February 1953, when it was slated to be “the first

feature-length entertainment film to be made in the Cinerama process,” though ultimately the musical did not make it to the screen until 1969 when extra songs were added by Lerner and André Previn.

57

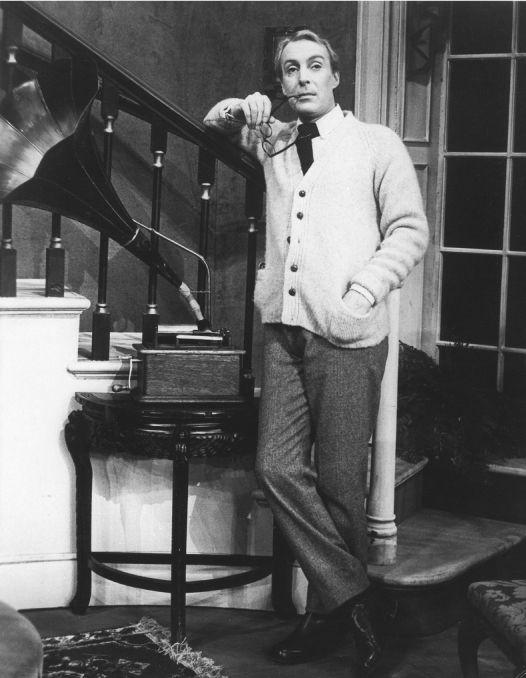

Ian Richardson as Higgins in the 1976 Broadway revival of

My Fair Lady

(Photofest)

The

Los Angeles Times

had also reported on the movie on February 11, stating that it was “all but set for

Paint Your Wagon

to go before the cameras June 8 as the first Cinerama production here, and a big musical it will be.” In

addition to the Lerner and Loewe numbers from Broadway, the article continued, “Lerner and Arthur Schwartz are to write eight new songs.”

58

Seven of these songs have survived in piano-vocal manuscript and are in the Arthur Schwartz Collection at the Library of Congress. Two of them lack lyrics, but collectively these numbers represent a substantial amount of work. “Bonanza!” is a lively jig in 6/8 time, and like all these songs, it shows Schwartz’s lightness of touch in combining the thirty-two-bar song form with the atmosphere of the Wild West. “Californey Never Looked So Good” is a similarly upbeat and optimistic number, and though the lyrics for “Kentucky” have not survived, the use of common time, the tempo indication of

Allegretto

, and the persistently underlined D-major tonality suggest a positive depiction of the state. No words remain for “Paint Your Wagon,” either, but it is marked “Slowly” and features the conventional dotted-rhythm accompaniment of western music, apparently used (as far as one can tell) to poignant effect. Although “Noah was a Wisdom Man” maintains the western

tinta

of the rest of the numbers, it also serves as a reminder of the Dietz-Schwartz songs of the 1930s revues, both in its fast harmonic rhythm and witty lyrics (“For after days afloat, it has been wrote, / Nobody wanted to leave the boat”). The finest numbers, however, are “Over the Purple Hills” and “There’s Always One You Can’t Forget,” both of which are gentle, romantic ballads in E-flat major.

59

At their best, one can see how the fruits of the Lerner-Schwartz alliance might have boded well for future collaborations. Evidently the pair were able to work together fairly quickly, for they came up with these seven songs in only a few months, and a script is also extant in the private collection of Paul Schwartz, the composer’s son.

60

No less importantly, it is easy to understand why Lerner might have turned to Schwartz: as a composer, one of his stylistic facets was the ability to create a lot of expressive internal harmonic movement in a song, something that he shared with Loewe. Had the film come to pass, Lerner and Schwartz might have gone on to create a string of works together, and of course the announcement of two stage works in addition to

Paint Your Wagon

shows that this was their intention.

But at this point, a somewhat surprising swap of composers took place. With no progress apparently having been made on

Li’l Abner

, Schwartz signed up to write the score for a show called

By the Beautiful Sea

, starring the Broadway veteran Shirley Booth (who had previously featured in Schwartz’s

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

). Louis Calta’s

New York Times

column reported on November 12, 1953, that the composer Burton Lane, who had earlier collaborated with Lerner on the Fred Astaire film

Royal Wedding

, had abruptly withdrawn from

By the Beautiful Sea

“because of changes made in the story line,” and that

Schwartz would now take over. His work on the new show (due to open in late February 1954) would “not interfere with the plans for

Li’l Abner

, the musical based on Al Capp’s comic strip,” which, according to Calta, “will go into rehearsal next August.”

61

But Schwartz’s defection to another show seems to have invoked Lerner’s ire, according to the composer’s son, Jonathan Schwartz. Years later, the latter explained how his father had been in need of money and could not afford to wait for the notoriously slow Lerner to get around to working on their projected stage musicals, hence he went to write

By the Beautiful Sea

.

62

Lerner broke off the relationship with Schwartz and teamed up with Lane, who had left the

Beautiful Sea

show, to write

Li’l Abner

. On June 21, 1954, it was reported that

Abner

was one of three musicals under consideration by director Robert Lewis. According to Zolotow’s

New York Times

column, “Herman Levin expects to have the Alan Jay Lerner–Burton Lane show in shape for a November rehearsal date.”

63

Another article of August 15, 1954, confirmed that Lerner was “Now busy collaborating with Burton Lane on the forthcoming stage musicalization of the

Li’l Abner

comic strip.”

64

But it was not to be. On seeing Gabriel Pascal’s obituary in early July, Lerner thought once more of

Pygmalion

, and on meeting up with Loewe again on the persuasion of Lerner’s then-wife, Nancy Olson, he realized they could work together on the play.

65

Composer and lyricist put everything else aside and set to work. The entrance of Herman Levin into the story at this stage was crucial, since although the

Li’l Abner

musical did not come to pass in this form (it eventually reached the stage in 1956 with a book by Norman Panama and Melvin Frank, music by Gene De Paul, and lyrics by Johnny Mercer), it was Levin’s determination that brought

My Fair Lady

about in the face of adversity. Lerner informed Levin that he was putting

Li’l Abner

to bed for the time being and that he wanted Levin to produce

Pygmalion

instead, with Loewe as the composer.

66

The producer was understandably surprised but trusted Lerner, and there was now no looking back.

FROM PAGE TO STAGE

THE GENESIS OF

MY FAIR LADY

WITH LEVIN, LERNER, AND LOEWE

On October 11, 1954, Herman Levin announced to the press that he was to produce Lerner and Loewe’s musical version of

Pygmalion

. Sam Zolotow reported that the Lerner-Lane treatment of

Li’l Abner

had been deferred and that “

Pygmalion

may be put on here.”

1

This caused dismay and shock in the Theatre Guild camp, and Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner wrote a letter about the matter to Lerner. He responded on October 19:

My reaction is puzzlement and bewilderment. Pascal, not The Theatre Guild, was the owner of the rights, and it was he who approached us about the project in California, much before any arrangement with The Theatre Guild … Gaby was negotiating with Thompson and Allen before he died. Suppose that negotiation had been concluded and they had approached Fritz and me and we had accepted? Would you have written us as you did? Of course not. The property belonged to Pascal as it now belongs to his estate, and it is with his estate we negotiated.

2

Lerner’s letter went on to explain that he and Loewe did not return to the Theatre Guild with the project because of the difficulties they had over the royalty agreement. He claimed that everybody else “held firm on their royalty and only the author was asked to accept less than minimum. My ego was not troubled, but my sense of fairness was definitely jarred.” He ended, triumphantly: “Suffice to say I have improved my lot with Herman Levin.” The response from the Theatre Guild was strong: “To say that we have been played a dirty trick is not a fair characterization of what has happened.”

3

But in spite of the Guild’s fury at having been left out of a project on which they had once worked so hard, Levin, Lerner, and Loewe moved on with the show.

The correspondence from Levin’s papers begins on October 2, 1954, with a letter from Noël Coward in London to Levin in New York, in which he stated that he was about to play cabaret seasons in London and New York, where he was due to arrive in the first week of December. The significance of this becomes clearer in Levin’s reply from October 15: “When you get here the first week in December, I hope that you will be able to spend an hour with Alan Lerner, Fritz Loewe and myself. We want to tell you of a project that may interest you.” Clearly Lerner and Loewe had revived the original idea of having Coward as Henry Higgins, but this letter almost ends all mention of Coward’s connection with the Broadway production. The meeting may have taken place, but on January 25, 1955, Coward sent Levin a very final refusal in which he indicated that he was committed elsewhere well into 1956.

4

No leading man for the show, then, but preparations were underway. Levin’s next move was to contact the designer Oliver Smith, his old friend and colleague from musicals such as Jule Styne’s

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

(1949) and Harold Rome’s

Bless You All

(1950), both of which Levin co-produced with Smith (who also designed them). On October 17, 1954, Smith wrote to Levin from Hollywood (where he was designing the film version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Oklahoma!

) in the wake of a brief visit to New York, giving some tantalizing details about the

Pygmalion

musical: “Please write me about

Pygmalion.

Are the rights cleared? I want to start soon working on ideas. I have some wonderful research here which will be absolutely terrific. … Send me a scenic outline so I can begin to think about

Pygmalion

soon.”

5

Smith’s eagerness to start work on what would become

My Fair Lady

is palpable. It is also interesting that he was the first member of the production team to be hired; indeed there appears to have been no debate as to which designer to use for the show. Levin replied to Smith on November 1 with a surprisingly early production date: “From what Alan and Fritzie tell me,

Pygmalion

is coming along beautifully, and if it continues that way and we can get our casting done in time, we should be in rehearsal by February 15th.”

6

So although very few letters from this period survive, Levin was evidently intent on getting the show on the stage within a few months: although he concedes that “I can’t promise the February 15th date, and we all know that February 15th could become September 15th”; he also asks, “If we do go in February … will you still be able to do it?”

The producer continues with a further important piece of information: “I’m having lunch with Cecil Beaton today, because I feel very strongly that he is the best one to do the costumes.” From this, one might infer that Levin was responsible for choosing Beaton for the show, though of course he had been in the running with the Theatre Guild’s potential version in

1952; however, Lerner claims that the choice was “unanimously agreed” upon and that the conversation with Beaton took place during Lerner, Loewe, and Levin’s trip to London in early 1955.

7

Also crucial to the genesis of the show is a final reference in the letter from Levin to Smith: “It’s much too early to send you a scenic plot,” he says, “because, though they’ve got the book outlined, they have been working mostly on songs.” Although Lerner never claimed to have written the script by this point, it seems surprising that so little had been prepared by way of a scenic outline: How were the songs motivated, if not by the plot? We know at the very least that a detailed synopsis had been produced for Mary Martin in 1952. Of course, Levin may have deliberately wished to resist unveiling specific information about the show while so much had yet to be decided, but it does indicate, if nothing else, that his February 1955 rehearsal date was rather optimistic.