Mac Hacks (29 page)

With

the lightweight security measures out of the way, we can

turn our attention to methods that don’t simply obfuscate the network

but actually encrypt its traffic. To put a finer point on the

difference: if you use one of the previous methods, your network may be

difficult to find, but all its traffic will be sent in plain text, so

anyone who bothers to intercept your traffic can follow exactly what is

going on with very little work. Adding WPA2 to your network makes it

much more difficult to see what’s actually being transmitted over your

network.

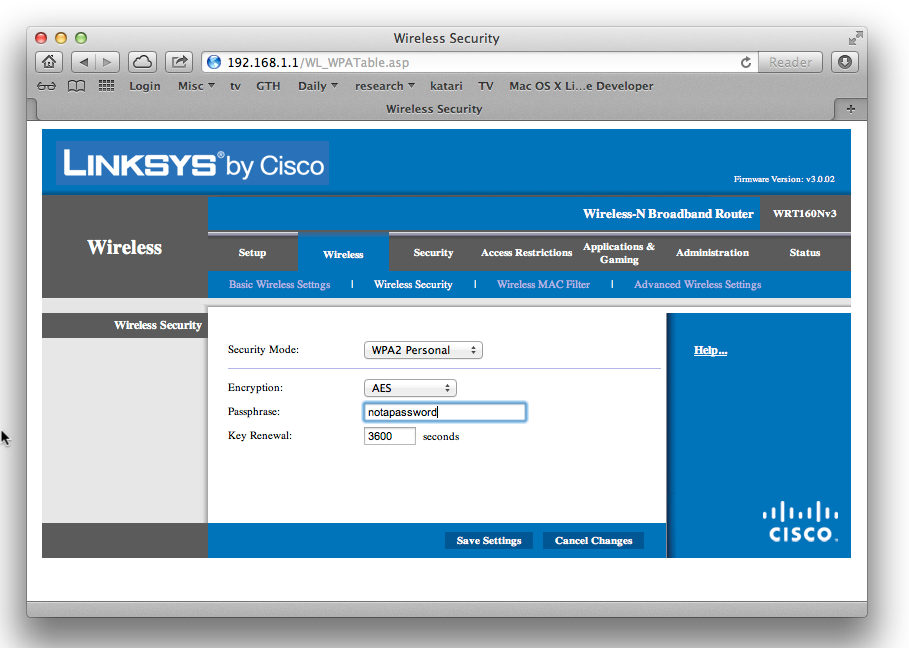

Your router likely has several security protocols built in,

leaving you to wonder which one is best for your particular needs.

Unfortunately, most of the security protocols with your router have been

compromised by nefarious types, leaving WPA2 (short for WiFi Protected

Access II) as the only sensible option. Once you’ve decided to go with

WPA2, you have to decide which version of it is right for you. Most

routers come with two versions: WPA2 Personal and WPA2 Enterprise. The

difference isn’t trivial: WPA2 Personal relies on a pre-shared key (you

can get on the network if you know the password) (

Figure 9-10

), while WPA 2

Enterprise relies on network clients logging in with a username and

password. WPA2 Personal is your best bet for a home network.

it provides both ease of use and security.

Now

that you’ve made your choice, the good news is that the

work is almost done. The bad news is that the process isn’t as

straightforward as you would expect. With most routers, you can type any

password you wish into the WPA2 shared key field. For example, if I set

a password to “qwerty,” the router will happily accept that key. But

trying to enter that key to gain access to the router via WiFi won’t

work—OS X won’t let you enter any password that’s less than eight

characters. Why? It turns out that OS X is smarter than your router. The

WPA2 specification demands a key length of between 8 and 63 characters.

Your router wasn’t smart enough to tell you that, but OS X is. Now that

you know that, all you have to do is choose an 8-character (or longer)

password and enter it in your router’s settings. If you’re successful, a

small lock icon should be displayed next to the name of your network

when you’re browsing nearby wireless networks.

At

this point you’re feeling pretty good. You’ve locked your

WiFi down so freeloaders can’t surf for free. But there’s one more thing

to consider—the security of your password. A password like 123GOVOLS is

memorable, but it’s also very vulnerable. WPA2 networks aren’t

susceptible to the tricks that WEP networks are, but they

can

be compromised by

dictionary

attacks

(where passwords are tried from a table of common

passwords and words). How devoted are people to trying a zillion network

passwords to see if any of them work? Visit

www.renderlab.net

where you can find a rainbow of tables (useful for cracking) that range

up to 33 GB in size.

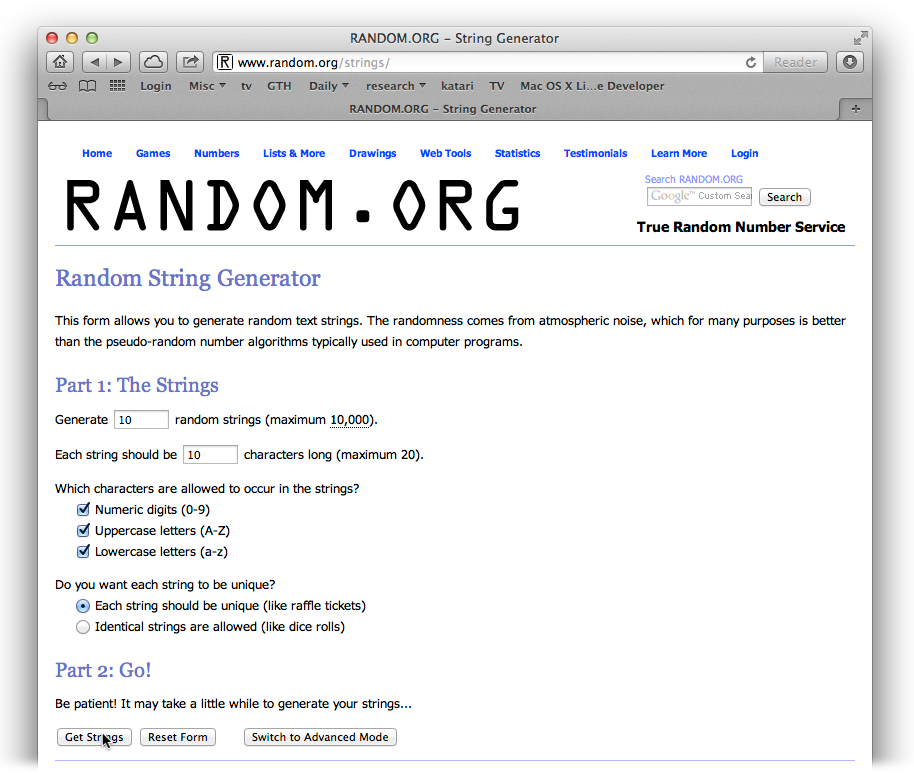

So why not make a really good password? You won’t be entering it

often, your Mac will remember it for you, and you’ll be secure in the

knowledge that it will take a really long time to crack your network. A

quick trip to

this

page

gives you access to a tool that generates random sequences

of letters, numbers, or a mix of the two (

Figure 9-11

). Length is

crucial: a randomly generated passphrase of 14 letters is considered

very secure, so set the page to output just such a string.

can’t find any of them in a dictionary.

You’ll have to really reach to find some obvious phrase or pattern

in any of the generated strings. This means they’re hard to crack but

also very difficult to memorize. Fortunately, ease of memorization isn’t

a big deal when you’re setting a WiFi password, since you’ll only have

to enter it once on each Mac you use.

Once you’ve generated and chosen a string, write it down. Store it

in OS X’s Keychain app or somewhere else safe. Paste the new pre-shared

password into the appropriate spot on your router’s configuration page

and then save the new setting. The router will restart, safe from prying

eyes and bandwidth leeches.

To get your Mac back on the network, select the network you’ve

secured and enter the password into the required

field.

You’ve changed your network’s name and password, hidden its SSID,

crammed a completely random 14-letter phrase in as a WPA2 password—and

then forgotten or lost every scrap of information you used for the

settings. If you try to unplug your router hoping the defaults will be

restored, you’re going to be stymied. So how can you get your router

back when you’ve been blocked by your own security?

Don’t worry: your router hasn’t become a brick of plastic,

circuitry, and electronics. Most

routers have a recessed reset button that you can press

with a pencil tip or paperclip to return your router to its factory

defaults. Hit the reset button and you can start the process all over

again.

. Use Your Mac as an Access Point

In

case you’re feeling generous, this hack shows you how to

share an Ethernet connection with your iPad- and iPhone-using friends via

WiFi.

Your Mac is a sharing machine! Plug in a printer, and it can share

that; toss some files into your Public folder, and users can get to them

over the LAN. Want to run a site from your Mac? No problem. But the

sharing doesn’t end there: you can even go so far as to share your

Internet connection with those around you who can’t connect, or with your

wireless gaming console.

The situation where you might want to share your Internet connection

without access to a router seems a bit suspect at first. Just where are

you going to be that doesn’t have an Internet connection? And if you have

an Internet connection, why would you want to share it; heck your laptop

is already connected!

It seems an unlikely scenario until it happens to you—then it seems

like Apple really knew what it was doing when it added the ability to

share your Internet connection via the Network preference pane. Typically,

the scenario goes something like this: you’re in a hotel room or some

other not-home place where you can get Internet via an Ethernet cable but

not wirelessly. Of course, you’re sharing the room, and the other person

also has a laptop. Naturally, you both want to hop on the Internet at the

same time. Instead of the predictable knife fight over who gets to use the

sole Ethernet hookup, hook up your Mac and use it to

share

the Internet connection.

That’s the most common way to use this hack, but not the only one.

Some ISPs give you a modem but don’t really require that you use it; the

Internet connection will work just as well if you plug the Ethernet cable

straight in to the back of your Mac. The obvious downside of this method

is that you can only connect one device. With this hack, you can use your

Mac as an access point so you can get rid of the router and associated

cables.

The good news is that this is a very easy trick to pull off. The

bad news is that the process includes an ominous warning that may

frighten the uninitiated. So let’s get initiated.

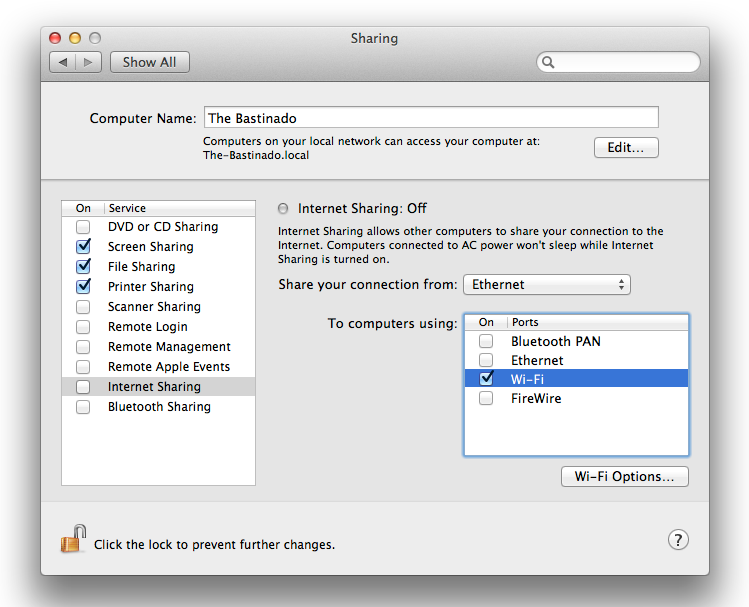

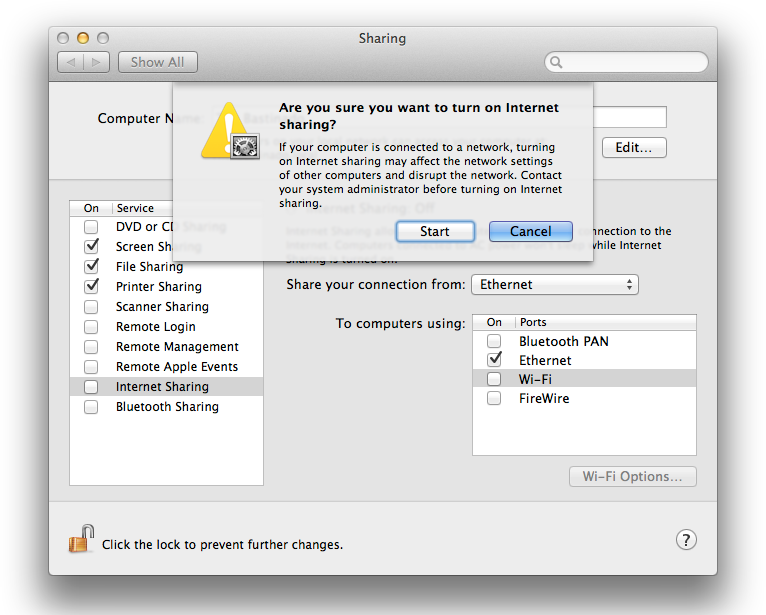

Head to System Preferences→Sharing and configure the preference

pane as required for your particular situation. In this example, an

Ethernet connection will be shared over WiFi (

Figure 9-12

). The specific setup

you’ll want will depend on your particular situation. No matter what

configuration you desire, you have to perform this step before OS X will

let you turn on Internet sharing.

before OS X will let you share it. Sharing options vary by machine—for

example, those with newer Macs will find options for Thunderbolt that

aren’t shown here.

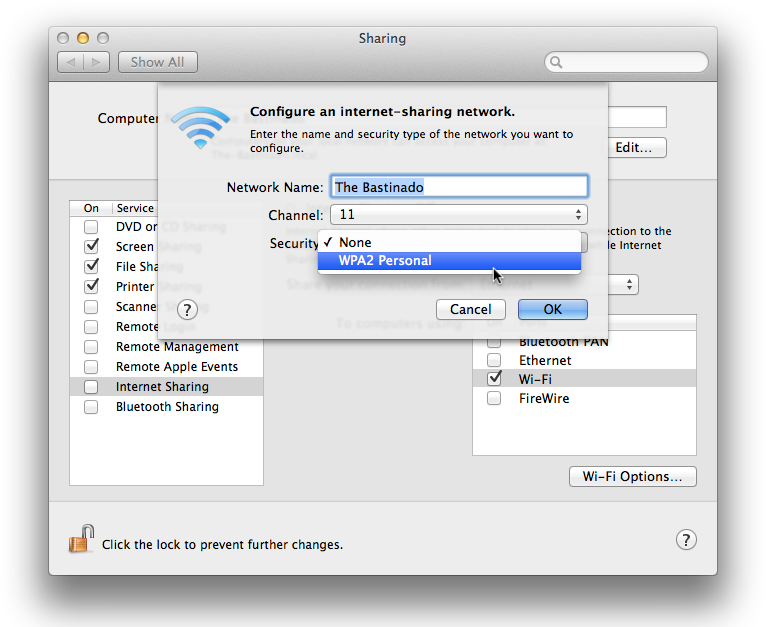

The exact procedure depends on how you want to share the Internet

connection. In the case of sharing it over WiFi (likely the most common

scenario), you get to make a few choices you won’t have to make when

choosing other configurations. To proceed, click the Wi-Fi Options

button. As shown in

Figure 9-13

, you’ll be able to

decide whether or not to rename your network (the default name is the

same name as your computer), what channel you want to use, and whether

your network should require a WPA2 password. Note that you’ll only have

to make these decisions (as mundane as they may be) if you click the

Wi-Fi Options button; otherwise OS X will just go with default

values.

exact options you’re presented depend on the configurations you are

using; you won’t see options exactly like these unless you are sharing

from Ethernet to WiFi.

Once you’ve got everything set up the way you want, it’s time to

start sharing that connection. This is where the ominous warnings begin.

Instead of simply checking the box next to Internet Sharing and having

the sharing begin, you get a stern warning that you’re about to mess up

everyone’s Internet settings and instructions to contact the system

administrator (

Figure 9-14

).

The chances of you breaking the Internet are slim to none, so go

ahead and click Start in the warning box to start the sharing process.

You’ll know you’re successful when the AirPort menulet changes from its

usual broadcast icon to a quarter pizza slice with an up arrow (see

Figure 9-15

).

That’s all there is to it. You can now hook up any device you

would

usually

hook up to a router to your Mac

instead and enjoy all the benefits

of connectivity.

work but it’s your home system, so go ahead! Don’t worry—you won’t

break the Internet.

all rejoice that their data plan can remain unscathed while they

consume bandwidth.