Madam (13 page)

Authors: Cari Lynn

“Eat up,” said Pete. “There’s gonna be trays of food walking all around you at that party, and you aren’t gonna be allowed any of it.”

“Leave him be, Pete,” Hattie scolded. Having no children of her own to flap over, she looked to Ferdinand with parental pride. “He’s going tonight with the honor of playing, not eating.”

Pete laughed. “They know how to get their money’s worth, then.”

Ferdinand smiled a mouth full of stew, knowing it was true—no matter that he was thin as a matchstick, he could eat as if there were five of him.

Pete untied his apron and retired it to a hook, then pulled a chair next to Ferdinand and sank onto it. “Ah, don’t it feel good to sit for a minute,” he sighed. “So, how’s your composing coming along?”

Ferdinand forced his smile to remain. “Slowly,” he said, hoping the subject wouldn’t linger. “Doesn’t matter for tonight, though. No one will be angling to hear my original works. I suspect common Dixieland will suit those fancy dans just fine.”

“You’re studying so hard,” Pete said, “you’re gonna be a professor of the piano one day soon.”

Ferdinand looked up from his jambalaya. “I like that,” he mused. “Professor of the piano.”

But in return he got Pete’s finger wagging in his face. “I said one day. Don’t go getting big-headed now.”

As Ferd scraped the last of the jambalaya, he began to feel his nerves kick up again. If he couldn’t get back to his music to calm him, he could at least talk about it. He nodded to Pete. “You ever heard any of the greats play some rag? Now, those’re the real professors of the piano.”

“Don’t believe I have,” said Pete.

“I snuck into Frenchman’s but once,” Ferd said. “It’s the late-night saloon at the corner of Bienville and Villere. You’d never know anything was happening there because by ‘late-night,’ they mean things don’t get started until near four a.m.!” At this, Hattie gave a disapproving smirk from where she sat with a bucket of fresh shrimp, peeling then tossing them on a block of ice.

“So I went there to see Tony Jackson,” Ferd continued. “Now, when Mistah Jackson walks through the door, anyone should get up from the piano stool, don’t matter if you’re Alfred Wilson or Albert Cahill or Kid Ross. Get up from that piano, you’re hurting its feelings! Let Tony play. I should tell you, Tony is not a bit good-looking, but he is the single-handed greatest entertainer in the world.”

“You’ll be right smart too, Ferd,” Hattie said dutifully.

Ferdinand smiled softly; he wished his own relations had offered up just an ounce of the Lalas’ applause. Ferd’s father had known Pete Lala since they were in short pants, and Pete had been at Ferdinand’s christening. Pete was there, too, when Ferd’s father was kicked out of the house after liquor ruined him.

But throughout the hard times, there was always music in the LaMenthe house, with instruments everywhere. Horns, harmonicas, a piano of course, drums, a steel guitar, a Jew’s harp, even a zither, all having been collected by his mama, his grandmère, his godmother, and even Mimi, his great-grandmother. However, the patriarchs of the family held far less musical appreciation. More so, Ferd’s stepdaddy didn’t take kindly to him playing what he deemed “a lady’s instrument” and threatened to throw Ferd out on his ear if he caught him at the piano. Ferd confided to Pete that he could no more stop playing than stop eating, and he did both to the extreme and with aplomb. And then Ferd’s dear mama passed on to heaven.

It had been Ferd’s hope when he and his little sister went to live with Grandmère that things would change, for Grandmère had been classically trained on the piano. But she was disinterested in Ferd’s musical aspirations, unless they were classical or church related. He knew Grandmère meant no harm, but she feared if she encouraged his music, he’d wind up without an honest job, a carousing tramp like his father.

When Ferd, longing for an audience not seated in pews, had asked Pete if he could play that old piano, he happened not to mention that Grandmère wouldn’t approve. Bricklayer, that was Grandmère’s plan for him. But when patrons began to talk up Ferd, he finally confessed to Pete that he was there without Grandmère’s knowledge. Reluctantly, the Lalas agreed not to say anything if they ran into her. Ferd was still surprised that word hadn’t made it back to Grandmère through one Creole circle or another, although he was certain he’d know the moment she found out.

Pete, however, was hopeful that Ferd’s grandmère would come around, and he couldn’t help but ask if she knew of Ferd’s honor that night.

Ferdinand sighed. “I’m still carryin’ on as if I were employed to wash your dishes every night. She thinks any person showing off a talent in public is

common

.”

“Oh, she’ll get on over it,” Pete reassured. “Your mama and papa, they’d have been mighty proud, that’s for certain.”

“Mama,” said Ferd, “she was proud of me just for opening my eyeballs every morning.”

The setting sun momentarily leveled with the front windows and hit Ferd in a way that made him tear up—or maybe it was just that he missed his mother. She was famous for her colorful stories and was undoubtedly the source of Ferd’s inherited gift of

yat

. He blinked away any tears before they could spill over, and resumed his talk as distraction.

“Papa? You knew the man better than that, Mistah Pete Lala! He played a mighty fine trombone, but blowin’ on a brass horn’s one thing. He was hardly different from my stepdaddy. Any man making piano music was a sissy cream puff to him. Surely I was meant to do more important things. . . .” Ferd trailed off as he suddenly realized the details of his father’s face had grown blurry in his mind’s eye.

Lala shifted uncomfortably, not having meant to stir up painful reminiscences. “Best get on,” he said quickly. “On up to higher ground, where it’s gonna be white as if it were snowin’ in New Orleans.”

Ferdinand wiped his mouth and rose from his seat, smoothing out his shirtsleeves. Hattie scurried over and, careful not to touch him with her shrimp-peel hands, gave an awkward but motherly hug. “I wrapped you a roll with jelly.” She motioned to a sack waiting by Ferd’s suit jacket.

Ferdinand was suddenly desperate to leave. He cascaded his jacket over his arm, plucked up the sack, and shuffled out the door. They waved after him, and he felt a bitter swell of emotion. He bit his bottom lip to suppress anything from bubbling to the surface. He wanted to feel nothing but the gentle breeze on his face. He crossed over Customhouse Street and headed in a direction he didn’t normally go: uptown.

C

HAPTER EIGHT

A

s the setting sun peeked through the canopy of giant Southern live oaks dripping with Spanish moss, a pink sheen fell upon the regal columns and immaculate white brick of the Saint Charles Avenue mansion belonging to Judge J. Alfred Beares.

Ferdinand climbed the steps, then stood at the imposing front door, attempting to work up the nerve to knock. He breathed in the aroma of sticky sap and the lemon perfume of magnolias just starting to bloom—a welcome change from his part of town, where the only good smells came from someone’s cooking.

His eyes fell upon a statue perched near the entrance: a female figure in a flowing Grecian robe holding a sword in one hand and dangling the scales of justice in the other. Ferd surmised that the judge must be a very serious fellow.

Reaching for his crimson silk handkerchief, he dabbed the sweat beads on his upper lip and forehead. The jambalaya began to churn in his stomach, and he chided himself for having eaten so ravenously before a big night like this. With a deep breath, he rapped the brass knocker.

As the door opened, Ferdinand snapped to attention. But he was surprised—and relieved—to see the pretty face of a young black maid.

“I’m playing the piano,” Ferdinand blurted out.

The maid raised an eyebrow.

“I mean, I’m not playing the piano presently. I’m standing at the door. But tonight, at the party.”

“Oh,” she said, then dropped her voice. “You’re s’posed to go ’round back, ya know.”

’Round back was where the help entered, that much he did know. Apparently she didn’t view him as the artist he thought he was.

Coyly, she glanced over her shoulders, and, seeing no one, she quickly beckoned him inside. He scooted in. Stepping foot in the foyer, he couldn’t help but give an immediate awe-filled look around, his gaze moving from the lofty, scalloped ceilings, to the crystal chandeliers, to a wall-sized tapestry depicting a regal fox hunt.

“There’s the piano,” the maid said, pointing across the parlor.

Mouth agape, Ferdinand caught himself, realizing he’d forgotten the manners Grandmère spent years hammering into him. He refocused on the pretty maid. “Miss, sorry for my impoliteness. My name’s Ferdinand LaMenthe.”

She gave him a shy smile and a requisite nod but didn’t return the introduction.

He took the opportunity to lean in closer, as if letting her in on a secret. “This is the fanciest gig I ever played,” he said. “But don’t tell no one, now.”

Again she smiled, a coquettishness toying at the corners of her mouth. Unable to help it, Ferd rambled on, letting her know that he was a classically trained pianist. “Efficient on the violin and guitar, too,” he added. “Not meaning to brag, but before I was even in short pants, I’d mastered playing the tin pan.” He’d now made her giggle.

“Aw, don’t worry none, Mistah LaMenthe,” she said. “Them all be stupid drunk by half past. Won’t care if ya’s playing the piano or a kazoo.”

Ferdinand was struck dumb. This was not quite the sentiment he was after. She offered a small curtsy, then scurried back to the kitchen. How piteous, Ferd thought. He mumbled to himself,

Even a blind hog can find an acorn.

No matter; he was here to play a piano, not a girl.

Stepping into the parlor, he ran his hand along a smooth marble chess table that sat between two imposing bear-claw chairs fit for monarchs. Above the fireplace, watching him with deep, unmoving eyes, was a gold-framed daguerreotype of the judge, dressed in his black robe, arms folded over his chest, a gavel in his hand. Ferdinand wondered if someday he might be affluent enough to have a likeness of himself presiding over his own house.

He arrived at a shiny, mahogany grand piano that took his breath away. Intricately carved fleur-de-lis decorated the piano’s empire-style legs, while delicate Baroque paintings of scenes from operas graced the side panels and bench. He was almost too afraid to touch the piano. Inching forward, he brushed his long fingers across the fallboard before gingerly sliding onto the bench. He lifted the cover and hovered his hands above the keys and just under the gold nameplate that said it all: STEINWAY & SONS.

Oh, when the trumpet sounds its call

Oh, when the trumpet sounds its call

Lord, how I want to be in that number

When the trumpet sounds its call.

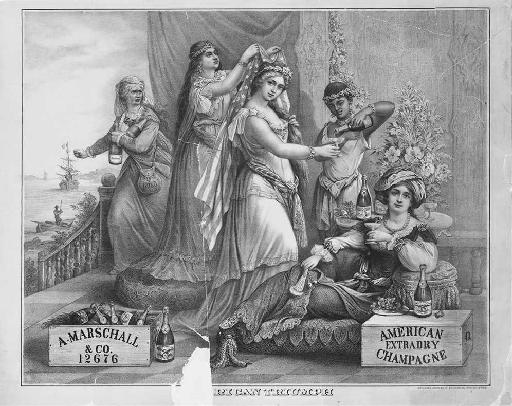

Ferdinand hummed the words to himself as he pounded out a lively “When the Saints Go Marching In” on the impeccable Steinway. It seemed strange to him to be playing “The Saints” when no one had died, but it was requested by an older white lady who seemed to be enjoying it heartily. Then again, it may have been the bottomless glass of Champagne in her hand that was raising her spirits. Either way, she’d made herself a fixture against the piano and was now leaning over Ferdinand to the point that the ribbons on her hat were dipping into her drink, while the tip of Ferd’s nose was practically in her cleavage. It was hardly as if Ferd needed to look at the keys while he played, but that’s exactly where he made sure to keep his gaze focused. “Oh, when the saints go marching in!”

The house was swollen with anyone who was anyone in New Orleans politics, business, and high-class white society. And at the center of it all was Judge Beares—hardly the austere man of his portrait. He waved a glass of bourbon as he gleefully held court.

“It’s the Frogs, I tell ya!” he shouted, casting a shower of saliva on every poor soul within a few-foot radius. “They started this whole thing when they shipped us their heathens.”