Madam (29 page)

Authors: Cari Lynn

“Yes, I’ve already had the privilege of touring that . . . place,” McCracken said.

Anderson stopped walking, turned to McCracken, and dramatically pushed the reporter’s notebook aside. “There are things the Countess has been keeping secret. Now, just between you and me, Mistah McCracken, the Countess is planning a room covered every inch with mirrors.”

McCracken smirked. “How refined.”

Anderson started up walking again, glancing back to make sure McCracken furtively noted the “secret.” “I’m sure the

Mascot

would be very interested to learn the multitudes of dollars our little District is already pumping into the economy of this fine city,” Anderson continued. He spotted George L’Hote, owner of all the lumber trucks scattered across the construction site. “And here’s a perfect example of the prosperity to be found as a result of the Story ordinance.” Anderson cupped his hands around his mouth and called out, “Mistah L’Hote!”

L’Hote turned, and his face flashed concern. Obligingly, he headed over.

“Good to see you, Tom,” L’Hote said, his voice tinged with caution.

“Likewise. I was just telling Mistah McCracken here, of the

Mascot

, how business is booming at an all-time high thanks to Storyville.”

“Business is good,” L’Hote said stiffly.

“Ah George, no need for modesty,” Anderson said, slapping L’Hote on the back. “Isn’t this the best year in the history of L’Hote Lumber Manufacturing Company?”

L’Hote’s face was slack. “We’re fortunate to be having a good year.”

Anderson noted L’Hote’s resistance. “Well, I couldn’t be happier with the lumber, George. Mistah McCracken, if you pardon my manners, I’d like to take advantage of Mistah L’Hote’s presence and talk a brief business.”

McCracken motioned to go right ahead, and Anderson ushered L’Hote out of earshot.

Leaning in, Anderson spoke quietly through pursed lips. “I heard a nasty, nasty rumor, George. Y’all aren’t requesting a petition to the court over the boundaries of Storyville, now, are you?”

L’Hote shifted nervously. “Tom, I’m in quite a pickle. My family home, my eight children and dear wife, we abide only a block from here. Surely you understand not exposing children to immoral conduct.”

“I ain’t a family man,” Anderson said flatly. “But what I do understand is that a wise man doesn’t take my money with one hand and then shove it up my ass with the other. Are you a wise man, Mistah L’Hote?”

L’Hote took a hard swallow before Anderson answered for him. “’Course you are, and a wise man knows when to keep his mouth shut.” He gave L’Hote another hearty slap on the back. “Glad we had this little talk, George. As I said, your lumber’s working out real well.”

L’Hote tried to speak but faltered, and instead hung his head as he walked away. Anderson turned back to McCracken and, hardly missing a beat, continued his charged rhetoric, bloviating as only the mayor of Storyville could.

“Mark my word, Mistah McCracken, and by that I mean you can quote me: people will cross the ocean just to set foot in Storyville.”

McCracken raised a skeptical eyebrow.

“It’s true,” Anderson insisted. “Life without pleasure”—he inhaled deep through his nostrils, sucking up the breeze of success— “ain’t no life at all.”

C

HAPTER TWENTY-TWO

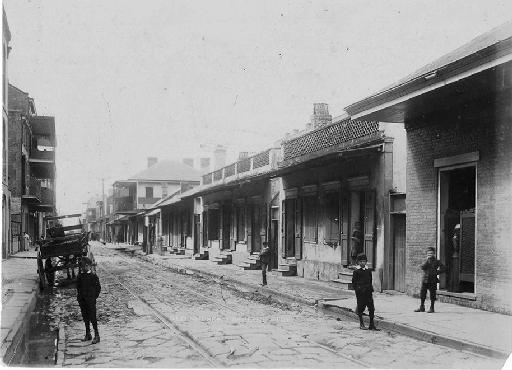

Urselines Street

F

rom the look of Venus Alley Mary sensed she was the only one feeling the weight of its impending close. Business bustled on as usual. Whores chirped about nothing except catty goings-on. Pimps collected their rent.

It knit at her that Tom Anderson hadn’t returned to the Alley with any sort of update. They were two weeks away from doom and no one even knew what their options were—let alone if there

were

options. It seemed the others just assumed they’d be accounted for, that Anderson had some equivalent to the Alley ready and waiting in the new district. But Mary doubted that was true. She hadn’t yet admitted it aloud, but it was becoming clear to her that Snitch was right when he said this shit hole wasn’t part of the plan.

She had hoped someone would’ve stepped up and tried to unite the whores and peet daddies in figuring out what to do next. But no one had taken the lead, and although Mary liked to think she would have risen to the task had Peter still been around, she now felt all her energy channeled into just getting through a day.

Oh, the effort it now took going through what used to be mindless motions. She had to practically force herself to bathe and choke down something to eat. And then there was the task of putting on a strong demeanor before Charlotte—even when Charlotte rushed in with stories of the Countess’s mansion and how Mary was pretty enough to be one of her girls. Mary had never lied to Charlotte before, but she’d dug her nails into her fist just to feel something other than the brick in her throat as she forced a tiny smile. “It takes more than pretty,” she’d said softly, then scooped up the bucket to head to the well even though she’d already brought in their water.

What she craved was to crumble in a heap and stay curled up for however long it took until the pain eased. But instead, what pounded in her head with each labored step were the words

two weeks

. Two weeks until Lord knew what was going to happen to everyone here. She wanted to shout at the top of her lungs, Why are y’all milling around like it’s any other day? What do you think is going to happen come next Friday?

Johns came and went, Mary forcing a coquettish grin. She no longer kept track, no longer counted the money they handed her. She just shoved it into her boot. Why bother? What was a nickel more or less when the days were numbered? She needed steady money, not pocket change.

Late that night, a black john approached as she was sitting on the stoop.

“Lookin’ for Beulah?” Mary asked.

“Lookin’ for anybody,” he said.

“Gotta come back in the morning when Beulah can serve you.”

His jaw tightened. “But I got two dollars for here and now.”

“Listen, mistah, I don’t give a yaller over the color of anybody’s skin, but you know as well as I do, it’s passable for a white man to take up with a Negra, but it ain’t lawful the other way around.”

He took two dollar bills from his wallet and held them out to Mary. She stared at the cash, then her eyes cautiously darted right and left. Seeing that no one was looking, she tilted her head, motioning him to go into her crib. “I’ll be a minute,” she said, her voice low.

She took a little stroll around the Alley, not wanting anyone to see her going in directly after a black man. When she felt all was clear, she went and serviced her john.

Sunup, sunset, the nondescript days blended into one another. Every morning Mary hoped to feel a small bit renewed, but each day was somehow just as painful, if not more so, than the one before. It was now a week before Storyville opened, a week before the demise of Venus Alley. One week before life as Mary knew it would come to a halt. She was prepared to beg on Basin Street if it came to that—not for tricks but for food. And it would, she figured, in the not-so-distant future, come to that.

Another john was on top of her, yet she didn’t feel anything. Squeezing her eyes shut, she counted the seconds until it would be over, when something hit her in the face. She bolted her head up to find the Voodoo doll resting next to her cheek. Her heart seemed to stop for a moment as she wondered from where the doll could have fallen. And then she realized it didn’t matter. It was the sign Lobrano was gone. She felt her body go cold. She wasn’t sure if she should rejoice or mourn. It was an eye for an eye, but now two lives were taken. And now she, too, had blood on her hands.

For the rest of the night, the Voodoo doll lay on her kip, for she was afraid to touch it. She wasn’t quite sure if she was afraid that jarring the doll might reverse the deed or that it might burn her skin for being a murderer. In the eyes of the law, she was no better than Lobrano. Even though the law barely acknowledged poor, unmarried girls like her.

She decided to leave her crib early, not wanting to run into Beulah and have to go through the motions for one more person. Besides, she wanted to get home and sit with Charlotte and the baby, the only comfort she had in the world. Charlotte put on a good face, focusing all her attention on the little one. She couldn’t fall apart, she was a mother now. And Mary couldn’t either; she was mother to them all.

As she opened the crib door she saw a small burlap bag waiting on the stoop. She eyed it warily before picking it up. Something was inside, something small and light. Slowly she pulled open the strings to reveal a bundled scrap of white cloth. As she unfurled the cloth, a locket fell into her palm. She gasped.

Faltering, she caught herself and stumbled back into the crib where she leaned against the wall before slinking down onto the floor. The locket, this locket, it looked exactly like the one her mama had, gold with a fleur-de-lis engraved on the front. But there was no possible way this could be Mama’s locket. Mary had last seen that locket the day Mama died, having tearfully taken it from her body shortly after mother and baby were pronounced dead. Mary had slept with it under her pillow that night. But in the morning, it was gone. She’d frantically looked everywhere. After a few days she’d solemnly accepted that the locket her mother had worn, the gold that had been smooth against her chest, was nowhere to be found. She’d reconciled herself by believing it must have been buried with Mama after all—it was the only consoling notion she could surmise.

And now, nearly ten years later, that locket was there still in every hazy memory she had of her mother. But why, why just days before her life came apart, would an identical locket appear at her doorstep?

There was only one way to know if it was authentic, if indeed it was Mama’s. With tears streaming down her cheeks, Mary slowly opened the locket. There, nestled inside, was a lock of auburn hair braided together with a lock of black hair. Mary began to shake as the memory flooded back. How she’d snipped a piece of Mama’s ginger hair then snipped a piece of her own. How she’d painstakingly braided the two, always wanting to keep Mama with her, and then nestled the braid into the locket—only to find it missing forever. Forever until today.