Madam (36 page)

Authors: Cari Lynn

She closed her crib door and straightened the pile of cash before slipping it into her cleavage. For the first time since Anderson had bestowed her with such good fortune she felt she was a decent enough person to deserve it.

Never again would she let anyone hurt her or her family the way Lobrano had. Never again would she need a man the way she thought she’d needed him. No, she didn’t need a pimp; she didn’t need a husband even. She vowed that as soon as she got ahead, she’d pay back her debt to Tom Anderson and become a fully independent woman. She would never again owe anyone anything.

A sugar cube dissolved into a glass of green absinthe, swirling it to a milky white. With a shaky hand, Lobrano brought the glass to his rotted mouth. He quivered as he took a deep swallow.

Too worried of being spotted if he went to the Pig Ankle, he’d wandered over to Bourbon Street and sat alone in a corner of The Absinthe Room, his collar turned up to shield his face. Sweaty and strung-out, he shot paranoid looks at the few patrons. He motioned to a barmaid. “’Nother,” he said breathily.

“Ya best dig in those deep pockets, ’cause you was short on your last one,” she snapped. He impatiently waved her away. Little did she know that his pockets were full—of stones. One drink more would have been nice, but what did it matter anyway? He’d be at the bottom of the Mississippi after this.

A husky voice rang out in the otherwise quiet bar. “Rough tonight. Rough tonight, batten down!”

Startled, Lobrano turned to see an old sailor in his seamen’s frock, shuffling through the bar with a cane. “Hear me now,” the sailor called out to the near-empty room. “The sea shows mercy to no man. But the spoils, they be there. Mark this!”

The few other patrons ignored him, but Lobrano’s eyes grew large. The old man shuffled closer. “You. A young sailor?” He pointed a knotty finger at Lobrano.

Lobrano shook his head.

“I believe you are,” the old man said, his finger inching closer and closer. Lobrano squeezed shut his eyes, attempting to shake off his absinthe haze. But when he opened his eyes, the old sailor was closer still.

“You. Turn turtle. Bayou bound. You.”

Lobrano slowly nodded. Yes, he was bound for the bottom, but how could this fogey have known?

“Must be time,” the sailor continued. “But only the full moon be revealin’ Lafitte’s gold.”

“Lafitte the pirate?” Lobrano asked.

The sailor gave a bulgy-eyed nod. “The spirit of Lafitte will guide you to forty gum trees. Batten down. Moon ain’t full yet. Must be overhead.” The sailor leaned closer, his white whiskers almost touching Lobrano. “Cursed, but it be there.”

The barmaid came by and gently hooked her hand around the old sailor’s elbow. She steered him in the direction of the door. “Sorry, ain’t no scraps for ya tonight, Ollie,” she said. “Best be gettin’ on now, we’re ’bout closin’ up.”

Ollie looked at her meekly, then shuffled out the door.

His vision fuzzy, Lobrano watched the old sailor go. “Lafitte’s gold,” he marveled to himself. Then, as if trying to soak in the details, he repeated over and over, “Forty gum trees, forty gum trees, forty gum trees. Cursed, but it be there.”

Lobrano called over the barmaid. “Ya ever heard of Lafitte the pirate?” he asked.

“Who me?” the barmaid said. Irritated, Lobrano turned to face the rest of the near-empty bar. “Anyone here know of Lafitte?” The few folks barely looked his way, thinking he was either drunk as a doornail or demented in the head—or both.

The barkeep piped up. “Lafitte and Andrew Jackson planned the Battle of New Orleans right upstairs.”

Lobrano looked up at the ceiling, astonished. “What about the contraband? Lafitte’s gold?”

“Supposed to be buried along the bayou, ain’t it?” a grizzled man at the other end of the bar called out. “Never heard of anyone findin’ nothin’.”

“But do ya know anyone who’s gone looking?” Lobrano asked, leaning on the edge of the stool.

“Can’t say I do. Supposed to be haunted, that gold.” The man took a sip of his absinthe. “Like half the things ’round here.”

“Forty gum trees, under a full moon, forty gum trees,” Lobrano chanted. Visions appeared before his eyes: a pirate stealing through the night, holding a purse bulging with gold coins that he dropped like breadcrumbs along the swampland. Lobrano could make out every detail of Lafitte’s long-nailed fingers reaching into the burlap bag. He could hear the clinking of coins, oh the multitude of coins! How each coin caught the glint of the moonlight before it disappeared into the earth.

“Barmaid!” Lobrano shouted. “I need something to write with!”

“This ain’t no schoolhouse, in case ya haven’t noticed,” she called back.

“It’s important. Need to write a note.”

The barmaid reluctantly brought over a pencil and square of paper. “You know how to write?” Lobrano asked her.

“My penmanship ain’t the best,” she said.

“Don’t matter. I need you to put, ‘To Mary.’”

The barmaid, concentrating now, wrote it in childlike block letters.

Lobrano continued, “Going to find the contraband.”

The barmaid cringed. “Don’t know how that ought to be spelled.”

“Gold. Going to find the gold. Half will be yours. . . .” He gulped. “To make up for what I done.”

The barmaid glanced up at Lobrano, and, for a moment, she felt of touch of sympathy—until her thoughts shifted to wondering just what it was the bastard had done.

Despite his spinning head, Lobrano noticed how her eyes had narrowed into disapproving slits. He wanted to tell her he wasn’t completely despicable, and that there were so many times he’d wanted to pawn that gold locket for cash, but he hadn’t. Hadn’t been able to squelch his sentimental feelings. He wanted to tell her that, but she was just a barmaid.

“How do you want it signed?” the barmaid asked.

“What?”

“She needs to know who it’s from.”

“She’ll know.”

“Ya gotta sign a letter,” she insisted.

“Fine. Sign it ‘Your Uncle.’”

She handed the letter to Lobrano, and he carefully folded it, then pressed it to his chest as he slid it under his suspenders, into his shirt pocket.

He staggered his way to Venus Alley, forgetting he was on the lam. He surveyed Mary’s crib from down the block. Seeing that the door was closed, he hurried up, slid the letter under the worn slats, and then quickly stumbled away.

Had Lobrano lingered, he would have seen a john emerge from the crib, the letter sticking to the sole of his muddy boot, unnoticed as he trudged away down the Alley.

Flabacher approached a shabby Baronne Street flat, grimacing as he turned the grimy doorknob. He ascended the staircase to apartment 2E and gave a solid knock. No response. He knocked again. Silence.

“Mister Bellocq?” he called. “The man at the Camera Club told me you were here.” He knocked a bit harder. “It’s been a number of days now, and I would like very much to see those photographs you’ve made, friend.” Flabacher waited, his ear to the door. “I also need to compensate you for your time and efforts.”

At that, the door opened.

Flabacher stepped inside. He was immediately unnerved by the sight: newspaper covered all the windows, and the walls were plastered with photographs. Photographs of tree stumps, doorways, lampposts, and every other mundane object in existence.

As Flabacher scanned what seemed to him like a big mess, Bellocq scurried back to his perch at a desk piled with thick books that he read through a magnifying glass.

“I beg your pardon if I’m interrupting,” Flabacher began, but Bellocq cut him off with a sharp point of his finger to a table. There, Flabacher saw a photograph of Lucinda. He squinted at it: she was half-naked and full-out asleep. The image repeated unchanged over several photos laid out in a row.

“Hmpff. Not exactly the yearbook-type pictures I had in mind,” Flabacher grunted. He stacked the photos, then placed them in his billfold. He took some dollar bills and looked around for where to set them. His gaze drifted toward a fishing wire strung from the back wall, photographs on clothespins dangling from it. Curious, Flabacher stepped around to see. At this, Bellocq began nervously chirping, waving his arms in the air like a monkey.

“All right, all right,” Flabacher said. “Calm down, fellow.”

Bellocq tried to catch his breath. “Please take your photographs and leave now,” he squeaked.

Flabacher opened the front door and tipped his hat.

Bellocq scurried to lock the door behind him, and, from the hallway, Flabacher could hear the deliberate screech of the door bolt as it slid into place.

“Odd fellow. Very, very odd fellow,” Flabacher muttered as he headed down the staircase.

Through a tiny spot not covered by newspaper, Bellocq peeked an eyeball out the window to watch Flabacher leave the building and wobble himself across the street. He watched until the hefty man disappeared from sight. He then stepped toward the fishing line, dipping behind it to face the photographs hung there to dry.

One after another after another, they were of Mary Deubler, draped in a tattered chippie and sitting in a straight-backed chair, her striped silk-stockinged legs crossed daintily. She was a contrast of raggedy, hard edges and gentle, dimpled girly features. From her scuffed buckle shoes to her tousled hair bun to the glass of Raleigh Rye in her hand, she was clearly nothing but an Alley whore. And yet, there was something so earnest about her, something genuine and unashamed in her face. She’d posed for the camera as if she felt beautiful and self-possessed, holding a glass to toast herself. There was a spark in this woman—Bellocq knew that showed through in the photograph.

He moved to a table, from which he lifted a heavy eight-inch by ten-inch glass plate negative and held it under a lamp. On it was the original image of Mary. He stared at it longingly, lovingly. Then he brought the blunt edge of a knife to the glass and grated it across the plate until her face was scratched out.

C

HAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

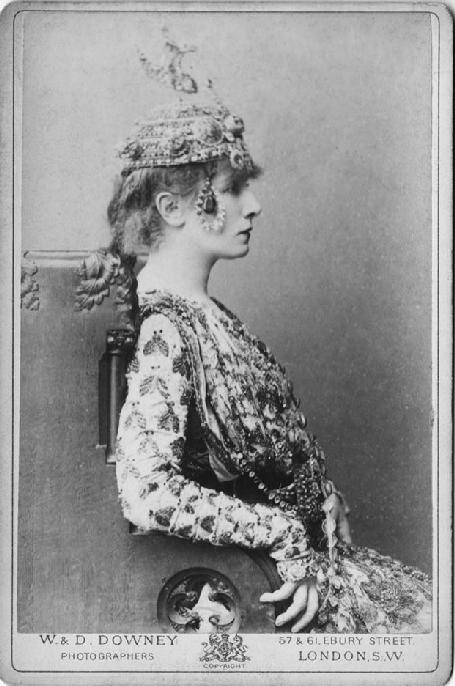

Actress Sarah Bernhardt

A

break in the heavy curtains shot a dagger of early morning sunlight into Lulu’s bedroom, rousing her from a fitful sleep. She contemplated rolling over for more beauty rest, but instead found herself compelled to move to the window and pull back the curtain. Squinting in the light, she adjusted her eyes to take in the vacant Victorian.

Throughout the days, she’d watched a parade of workmen, carting out old floorboards and wheelbarrows full of scraps, bringing in rolls of wallpaper and cans of paint. Cracked windowpanes were repaired, roof tiles were patched, doors were removed from their hinges and replaced. She’d found herself stealing to her room several times a day to watch the house, and she became consumed by the details. What pattern was the wallpaper? What color was the paint? Was that marble or granite? Slate or shale? Yesterday she’d balked as she watched men carefully handling long mirrors that were floor-to-ceiling high.

That Miss Arlington, whoever she was, better not be doing a mirrored room like my own!

None of Lulu’s searches on Josie Arlington had turned up fruitful. Even Snitch had responded blankly to the name. From this, Lulu surmised Josie Arlington was a pseudonym—but just where did Tom Anderson pluck up a nobody? And why did he want to turn this particular gal into a somebody?