Making a Point (26 page)

Authors: David Crystal

There's no hyphen in the 1996 printing.

Lingering is normal. Someone who is taught a particular use of the hyphen at age eight is likely to be still using it at age eighty-eight. Changes take a long time to become standard â about a century, in the case of the

today

forms, judging by what Mark Twain wrote in

The Atlantic Monthly

in 1880:

No one now writes

to day

or

to morrow

, and few people write

some thing

or

some body

; instead, we use

to-day

,

to-morrow

,

something

,

somebody

, and that we shall eventually come to use

today

and

tomorrow

is clear from the increasing frequency with which these forms are even now seen in carefully conducted journals.

An accurate prophet.

Semantics is always the main factor to be considered in deciding about hyphenation. Any fashionable trend will be overruled if it leads to ambiguity. So a hyphen is essential to distinguish such cases as:

I recovered/re-covered the book. [got it back/put a new cover on it]

They've made a small arms/small-arms deal. [a little one/ handguns only]

The remarks/re-marks are in the margin. [comments/new marks]

We need some more expert/more-expert advisers. [additional ones/people who know more]

I belong to an English teaching/English-teaching organization. [one from England/one that teaches English]

Puns abound, without punctuation. I know some high school teachers. Inadvertent puns too. I have a great grandfather.

Grammar is the next factor to be considered. Detailed accounts of hyphenation always attempt to find rules based on the grammatical structure of the compound â classifying them (or their elements) into nouns, verbs, and so on â but there are no rules, only trends. If it's a strong trend, this should certainly be pointed out, but with the qualification: ânot always'. For example, if the first element is an adverb, we see a well-established alternation. Before a noun, the adverb is attached with a hyphen; after a verb, it isn't:

This is a well-known principle.

The principle is well known.

The reason is to ensure that the word is recognized as an adverb, so the issue arises mainly in relation to words that look as if they could also be adjectives, as in

best-known

and

good-sized

. If the word clearly looks like an adverb, by ending in

-ly

, most traditional practice (Hart's

Rules

, once again) says: no hyphen. So we find both:

This is a carefully drawn picture.

The picture is carefully drawn.

Note: âmost' practice. Some style guides have allowed a hyphen, especially in Britain. But practice has increasingly followed the American preference for spaced words, which of course suits the present-day fashion to omit punctuation wherever it's semantically unnecessary.

Similarly, although prefixes and suffixes aren't usually hyphenated (

unhappy

,

powerful

), there probably will be a hyphen if there's a possible miscue (

co-worker, co-op

), and some prefixes tend to attract the hyphen more than others (such as

ex-husband

,

half-baked

). Usage here varies enormously, both regionally and institutionally. My despair over what to do with

no-one

is repeated regularly with

non-standard

and

neo-classical

.

Another example of a fairly clear-cut context is when a complex grammatical word-string is included within a larger construction, such as a noun phrase. Without the hyphens, the unusual word-strings can cause momentary confusion:

I met the on the spot reporter. > I met the on-the-spot reporter.

We are in a take it or leave it situation. > We are in a take-it-or-leave-it situation.

When the string is not included in a larger construction, the reason for the hyphen disappears:

The decision was made on the spot.

not

The decision was made on-the-spot.I want you to take it or leave it.

not

I want you to take-it-or-leave-it.

But well-established compounds may break this rule, so that we can find

up-to-date

, for example, used in both contexts; and some compounds of three words or more, such as

father-in-law

, never lose their hyphens, whichever part of a sentence they appear in.

There are a few other contexts where a hyphen is predictable. We see one in established lists, such as compound numerals (

thirty-six

,

three-quarters

). We see one where there are strong phonetic reasons to bind the elements together, such as in reduplicated or rhyming words (

helter-skelter

,

bowwow

,

tip-top

). We see one in coordinations (though in print the en-dash performs this role, p. 145), as in

an EnglishâFrench treaty

. And hyphens are obligatory when we need to show a syntactic relationship that extends over an intervening word:

pro- and anti-government

nineteenth- and twentieth-century movements

business-men and -women

eighteenth- and nineteenth-century fashions

These are called âhanging' (or âfloating') hyphens.

The hyphen has few other uses apart from its roles in line-breaking and compounding. But we do see it when writers want to convey prolongation or repetition with consonants or vowels:

D-d-d-do you mind [stammering, fear, teeth chattering, etc] He-e-elp, Ye-e-es [calling, tentativeness, uncertainty, etc] Ha-ha-ha, Boo-hoo-hoo [spasmodic articulations, as in laughs, giggles, sobs]

And hyphens also have a few technical functions. Dictionaries use them to show the way words di-vide in-to syl-lables â a technique also used by Victorian readers for young children (

Ja-net is talk-ing to Ri-chard

). Linguists use them to show word-elements

(-ed

,

ex

-). Numerical entities such as telephone numbers or dates use them (or dashes) to separate their elements (

6-7-1941

). URLs use them as a way of

separating words (

www.this-is-an-example.com

) â an option that is much discussed in web forums, as their presence raises issues to do with the ease of remembering an address and the efficiency with which the address can be located by a search engine.

Sometimes there's no punctuational solution to be found. Nobody has yet come up with a generally acceptable way of adding an inflection after a word ending in a vowel. How would you report the way someone danced the samba all night: they â

sambaed

?

samba'd

?

samba-d

?

samba-ed

? All we can do, in such cases, is rephrase. Similarly, there isn't a way of joining a hyphen (or an en-dash) to a spaced compound, as in the

New York-Chicago

or

Chicago-New York

express, without leaving one part of the compound curiously isolated. As already mentioned, punctuation doesn't solve all the problems of representing speech in writing.

Finally, we need to note the issues associated with the hyphen when it comes to marking personal or cultural identity. People can get very cross if someone misses out the hyphen in their double-barrelled first name (

Marie-Anne

) or surname (

Parry-Jones

). And personal hyphens can make the news. In 2013, it was reported that the New York rapper Jay-Z was henceforth going to spell his name without the hyphen. Tongue-in-cheek, a

Guardian

headline called this âearth-shattering news', and a âmassively disrespectful move against hyphens'. But the fact remains that the paper did report the change, and gave it a headline. And it wasn't the only paper to do so.

Cultural issues can arise relating to the presence or absence of a hyphen. Around 1900 in the USA there was a derogatory usage of âhyphenated Americans' â those who wanted to show their ethnic origin â and who said they were

Irish-American

,

Italian-American

, and so on. The practice was

widely attacked by, among many others, President Woodrow Wilson (in an address in support of the League of Nations in 1919): âAny man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready.' Strong stuff.

Place-names raise issues too. We have to learn which form a community prefers, as part of the spelling. So, we normally see

Newcastle-under-Lyme

alongside

Newcastle upon Tyne

. However, because the conventions are arbitrary or historically obscure, there's a great deal of vacillation. âExplore Stratford upon Avon' was the headline of the Shakespeare Country tourist website in 2014; and the first paragraph begins: âStratford-upon-Avon is a picturesque town â¦' Cultural history plays its part. In Quebec, place-names are hyphenated if they are French in origin (often at length, as in

Ste-Marthe-du-Cap-de-la-Madeleine

), but not if English.

The modern trend is to simplify names, and not to introduce hyphens, periods, and apostrophes. That's the policy of the US Board of Geographical Names, for example. But local feeling can force exceptions, and in some places there have been successful proposals to change a name by adding a hyphen. In January 2014, the cities of East Carbon and Sunnyside in Utah merged, resulting in East Carbon-Sunnyside. Not everybody liked it (the council vote was 7â4 in favour), so the decision was viewed as temporary. Any proposals for punctuational change in a place-name lead to heated public meetings and petitions. But hyphen-heat is nothing compared with the heat generated when people decide to mess around with the apostrophe, or decide to do something about it.

Hyphen-treasures

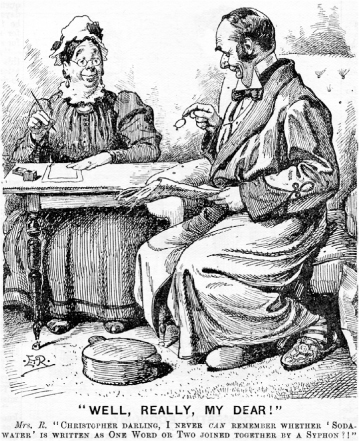

Divided opinions about hyphens go back a long time. Here's

Punch

(27 December 1856) objecting to what it calls a âGermanism in Journalism':

We very much wish that our contemporaries, in alluding to the pictures about to be exhibited at Manchester, would cease to denominate them as Art-Treasures. Why not call them Treasures of Art? Suppose we were to talk of Imagination-Works, meaning works of Imagination, should we not be deemed to talk very affected stuff? You might as well say Science-Discovery as Art-Treasure: or describe a learned or virtuous person as a learning-character, or a

virtue-man. A joke, on the same principle, might be termed a wit-speech, or a fun-saying. It is all very well to say mince-pie and plum-pudding: these are pleasant compounds, and not hashes of abstract and concrete, disagreeable to the sense of fitness. What, however, makes Art-Treasures a particularly disagreeable word is that it is a vile Germanism; and the same objection applies to all the various phrases consisting of “Art” skewered to some other word with a hyphen. Let us hear no more of art-coffee-pots, art-cream-jugs, art-fenders, art-fire-irons, art-cups, and art-saucers, art-sugar-tongs, and art-spoons: in short, no more artbosh, art-humbug, and art-twaddle. Stick to the QUEEN's English, and there stop. Corrupt it not by adulteration with German slang; do not teach the freeborn British Public to adopt the idioms, or rather idiotisms, of the language of despots and slaves.

28

Apostrophes: the past

Agonizing over apostrophes can land you in court. This was one of the outcomes of the amazing journey undertaken by American writer Jeff Deck and his bookseller friend Benjamin D Herson in 2007. They decided to âchange the world, one typo correction at a time', and created the Typo Eradication Advancement League (TEAL) to take the crusade forward. Armed with markers, chalk, and correction fluid, they went all over the USA, finding errors in public signage and correcting them. Missing, unnecessary, or misplaced apostrophes were one of the commonest targets. The journey took them a year, and they wrote it up in a delightful book,

The Great Typo Hunt

(2010). The headline on the inside jacket reads: âThe signs of the times are missing apostrophes.'

In Arizona, they went a correcting step too far. They visited the Grand Canyon, where they found in a viewing tower a chalkboard sign that included the word

womens'

. They corrected it to

women's

. Two months later, their trip complete, they received a summons from the National Park Service, charging them with defacing federal property and vandalizing a historical sign. It turned out that the sign had been hand-painted by the architect, Mary Colter, who had been commissioned to develop the Canyon site in the 1930s.

If Jeff and Benjamin had realized the significance of the sign, they of course wouldn't have touched it. Their aim was to correct modern errors, not to rewrite history. But ignorance

is no defence, and in court they pleaded guilty. They paid $3035 in restitution and received a year of probation, during which time they were forbidden to enter all National Parks and were banned from typo correcting. They were lucky. Another outcome would have been six months in jail.

There's no TEAL in Britain, but there is an Apostrophe Protection Society, started by journalist John Richards in 2001 âwith the specific aim of preserving the correct use of this currently much abused punctuation mark'. Its tone is moderate, unlike the haranguing voices of those who threaten to break the windows of any greengrocer seen to be advertising

potato's

:

We are aware of the way the English language is evolving during use, and do not intend any direct criticism of those who have made mistakes, but are just reminding all writers of English text, whether on notices or in documents of any type, of the correct usage of the apostrophe should you wish to put right mistakes you may have inadvertently made.

It's an appeal that many have listened to. The website had received over 1.7 million hits by early 2014.

Clearly there is a standard use of the apostrophe that has to be respected if people want to avoid the criticism of being uneducated, careless, or illiterate. This is a climate that has affected the whole of orthography (including spelling) since the eighteenth century, when a notion of âStandard English' finally emerged into the light after some 400 years of development. People became aware that they needed to use this variety of written English if they wanted to be thought educated and socially acceptable, and schoolteachers began to insist upon it. Standard (or âcorrect') punctuation, along with spelling, became one of its defining features.

William Cobbett was one who singled out the apostrophe

as a marker of social acceptability. In Letter 14 to his son (in

A Grammar of the English Language

, 1829) he calls it a âmark of elision', illustrates it by

don't

,

tho'

and

lov'd

, and offers this advice:

it is used properly enough in

poetry

; but, I beg you never to use it in prose in one single instance during your whole life. It ought to be called the mark, not of

elision

, but of

laziness

and

vulgarity

. It is necessary as the mark of the possessive case of nouns ⦠That is its use, and any other employment of it is an abuse.

While the perceived misuse of any punctuation mark would come in for criticism, the apostrophe does seem to have attracted more vituperation than any other, especially since the mid-twentieth century. And the question that remains unasked, in all the accounts of punctuation that I have read, is: why?

A clue lies in the time-scale of its arrival in English. The apostrophe arrived very late, compared with most other marks, in the closing decades of the sixteenth century, and took a long time to develop its present range of standard usage. Grammarians and printers were still trying to work out what the relevant rules were even at the end of the nineteenth century. They weren't entirely successful, leaving a number of unresolved issues over usage that generated further variation and associated controversy.

English did without apostrophes for almost a thousand years. The meanings conveyed by this mark were handled in other ways. Anglo-Saxon scribes would show an omitted letter by a horizontal mark over a letter (there's an example on p. 12). Possession was expressed through an inflectional ending on a noun (the genitive), most often

-es

(

scip

= ship;

scipes

= ship's), commonly spelled

-ys

or

-is

in the fifteenth century. Its pronunciation as a separate syllable died out, and

the

es

spelling eventually simplified to

s

, hence the modern form. All of this happened long before the apostrophe arrived in English â which is why it's not very accurate to say, as some present-day pundits do, that the mark was originally used to show the omission of genitive

e

.

Nor, incidentally, is there any truth in the story that the modern

's

is a shortening of an older form

his

. A construction of the type

the kyng hys sonne

was indeed common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and can be traced back to early Middle English. But its origin lies in the way

his

was pronounced without the

h

when it was unstressed (as it still is today in such contexts as

I saw his mother in town

). The pronunciation of

prince his son

was thus the same as

princes son

(= prince's son), so the two usages became confused. Over time, the

his

construction began to influence other nouns: we find it being used after women as well as men, as in

my moder ys sake

and later

Mrs. Francis her mariage

, and then with plurals, as in

you should translate Chillingworth and Canterbury their books

. We can still encounter the old use today, such as

for Jesus Christ his sake

in

The Book of Common Prayer

. The emergence of the apostrophe has nothing to do with the history of this syntactic construction.

The apostrophe's origins lie in Europe, where early sixteenth-century printers introduced it (based on Greek practice) to show the omission of a letter (usually, showing the elision of a vowel in speech). Its earliest appearance in England is in a book printed by John Day in 1559: William Cunningham's

The Cosmographical Glasse

. It was definitely used as a sign of omission there, not possession: we see

the partes of th' earth

but

moones age

. Ben Jonson, in his

English Grammar

(early 1600s), devotes the entire first chapter of his section on syntax to the apostrophus, âthe rejecting of a vowel from the beginning or ending of a word', as seen in

heav'n

or

desir'st

. He is very keen that apostrophes should be used, complaining that âmany times, through the negligence of writers and printers, [it] is quite omitted'.

It wasn't only negligence. There was a genuine uncertainty over how this new punctuation mark was to be used. Sometimes there would be an omission with no apostrophe at all:

Will you ha the truth on't

, says the Clown in

Hamlet

(in the First Folio edition) â not

ha'

. And a colloquial form of

he

turns up as

a

as well as

âa

and

a'

. We see it used to represent single letters (

th'

for

the

), two letters ('

em

for

them

), and even whole words (

'faith

for

in faith

,

'sblood

for

God's blood

).

Writers and typesetters â worried about the possible ambiguity in such a sentence as

these are the kings

â then began to use the apostrophe to mark the possessive option, but in a very unsure and erratic way. We see far more examples of possessives lacking an apostrophe than showing one. If the noun was a proper name, there is often one present (

Gonzago's wife

,

Apollo's temple

), but we also see a vacillation even in a single line:

Did Romeo's hand shed Tybalts blood

. If the noun wasn't a name, it would usually be absent, whether animate (

schoole-boyes teares

) or inanimate (

the fields chiefe flower

). But a developing sense that apostrophe = possession is evident, not only in nouns but also in pronouns. We see such spellings as

her's

,

our's

, and

it's

.

The typesetters also found the apostrophe a useful solution to unusual or alien-looking words. When Malvolio finds Olivia's letter in

Twelfth Night

, we read:

these bee her very C's, her V's, and her T's

. The plurals of foreign loanwords also attracted them, especially when they ended in a vowel (

dilemma's

,

stanzo's

), but they were used with native words too, and after consonants as well as vowels (

these pardon mee's

;

hum's, and ha's

). It was the beginning of a long association of the apostrophe with plurality.

And an association with the letter

s

. As both genitives and regular plurals used that letter, it perhaps wasn't surprising to see Elizabethan typesetters developing something of a Pavlovian response: if a word ends in a vowel +

s

, then insert an apostrophe. So we see them appearing with present-tense third-person singulars:

doe's

,

see's

,

ha's

. Even sometimes with consonants:

me think's

. All the confusions that we're familiar with in present-day English are found in these early days. If a noun ends in

-s

, what's to be done? We see them experimenting with various solutions: omission (

Venus doves

), expansion (

Marses fierie steed

), older use (

Mars his heart

), and insertion â but not always in the right place (Calchas in

Troilus and Cressida

lives in

Calcha's house

).

During the seventeenth century a consensus over some of the uses began to emerge. Quite clearly there could be a problem of comprehension if there was no systematic way of distinguishing between possessives with a singular and a plural noun. Context is sometimes a help, as in these two Shakespearean examples:

the use of following

his

shows that it's a singular when King Henry says:Wilt thou, vpon the high and giddie Mast,

Seale vp the Ship-boyes Eyes, and rock his Braines â¦

(

Henry IV Part 2

3.1.19)the preceding syntax shows it's a plural when Coriolanus says:

The smiles of Knaues

Tent in my cheekes, and Schoole-boyes Teares take vp The Glasses of my sight â¦

(

Coriolanus

3.2.116)

But often context is no help, and the pressure to make a systematic distinction grew during the eighteenth century.

Lindley Murray, following earlier grammarians, recognizes the two conventions,

's

and

s'

, so we might think that this would solve the problem once and for all. But there remained doubts. Joseph Priestley in his

Rudiments of Grammar

(1761) worries about how to distinguish constructions that sound the same, such as

the princes injuries

, and suggests the best solution is to avoid the problem altogether and write

the injuries of princes

. And C P Mason's

English Grammar

(1876) shows how the idea of elision was still present in people's minds. He accepts that we need an apostrophe in the singular because it âmarks that the vowel of the syllabic suffix has been lost', but he goes on: âIt is therefore an unmeaning process to put the apostrophe after the plural

s

(as

birds'

), because no vowel has been dropped there.'

The situation was made more complicated by the views of spelling reformers, who had become increasingly energetic during the nineteenth century. George Bernard Shaw avoided apostrophes whenever he could, and robustly defended his practice in his âNotes on the Clarendon Press Rules for Compositors and Readers' (1902):

The apostrophes in ain't, don't, haven't, etc. look so ugly that the most careful printing cannot make a page of colloquial dialogue as handsome as a page of classical dialogue. Besides, shan't should be sha'n't, if the wretched pedantry of indicating the elision is to be carried out. I have written aint, dont, havnt [

sic

], shant, shouldnt, and wont for twenty years with perfect impunity, using the apostrophe only where its omission would suggest another word: for example, hell for he'll. There is not the faintest reason for persisting in the ugly and silly trick of peppering pages with these uncouth bacilli. I also write thats, whats, lets, for the colloquial forms of that is, what is, let us; and I have not yet been prosecuted.

It's impossible to say how influential Shaw's views were, but they do illustrate the large divide between those who found apostrophes an irritation and those who introduced them in all possible places (

1920's

,

NCO's

, and so on).

The point to note is that, even as late as 150 years ago, experts were still not in agreement over all uses of the apostrophe. Nouns ending in

-s

continued to be a particular worry:

Keats' poems

or

Keats's poems

. And people didn't know what to do with pronouns:

theirs

or

their's

?

its

or

it's

? After all, it was reasoned, if the apostrophe marks possession, then surely it should be used in pronouns as well as nouns? If we have

the dog's bowl

, then why not

it's bowl

? And if

the dogs' bowl

, why not

the bowl was their's

?