Making a Point (23 page)

Authors: David Crystal

Still, if the meaning warrants it, a comma can nonetheless have a reinforcing function:

Smith waited for a few seconds, and then began to speak.

We can imagine an actor reading this novel-fragment aloud and pausing dramatically after

seconds

.

I've used the word âshort' several times in the last few paragraphs. The question of length. This is the factor that has disturbed everyone from Lindley Murray to Henry Fowler â and which caused all of them to throw in the towel when it came to formulating rules to explain the use of the comma.

The longer the clauses being connected â and especially the longer the opening one in a sequence â the more we're likely to introduce a comma to help the reader see the overall structure of what we're saying.

Smith is going to speak about cars using the same pictures that he had when he gave the talk in Edinburgh last year, and Brown is going to speak about bikes.

The function of the comma is now not so much grammatical as psycholinguistic. It gives the reader time to assimilate, time to mentally breathe.

Length would have been one of the factors that lay behind the worry of Cobbett (and others) about taste. It's at the heart of comma uncertainty, and we'll see it surfacing again in the next chapter. The reason that it's so central is because it unites the two approaches to punctuation that have dominated thinking in this field: the elocutional and the grammatical. The longer a construction, the more difficult it is to speak aloud; and the longer a construction, the more content it contains, and thus the more difficult it is to assimilate. But what one person might feel is âlong' another might feel is ânot so long'. That's where individual differences (âtaste') enter in. One person says, âI need a comma to make the meaning of this sentence clear'; another finds the same sentence perfectly understandable without a comma. It's because they have different processing abilities.

We're now entering the world of psycholinguistics. We know that there are limits governing how much we can hold in working memory at a time. Psycholinguist George Miller once defined it as âthe magic number seven, plus or minus two'. The formula should be seen as no more than a guideline, as it is affected by many factors; but it's a valuable mnemonic. And it shows how different people are.

There's an experiment anyone can do. Ask someone to repeat after you a list of items, such as a string of numbers between one and ten, increasing the length of the task by one each time. Say the items steadily, with a slight pause between each one:

You | Listener |

Four | Four |

Six, two | Six, two |

Eight, one, three | Eight, one, three |

The aim is to note when the listener finds it difficult to repeat the string confidently and correctly. Many people start to have trouble at around five elements, and seven seems a top limit for most, but some can handle up to nine with ease.

Now take the task to a more advanced level. If your listeners have failed at repeating six or seven items in a row, ask them if they would like to repeat eight items accurately. They will say yes, but wonder how. What you do is group the eight items into two sets of four, and speak them without pausing between the digits, a bit like reading out a long telephone number:

eight one three four / two nine six one

Most people can handle that. The rhythm and intonation help them keep such long strings in their head. And if we were to show this in writing, we could do so like this:

eight one three four, two nine six one

If we now look at sentences where there is variation over the use of the comma, we'll find that the point of greatest uncertainty comes when the first clause approaches five semantic units (content words, along with any grammatical modifiers, such as prepositions or articles). There's no

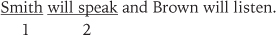

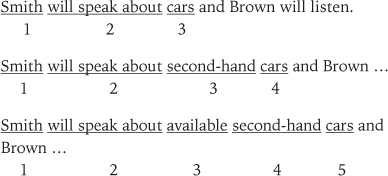

problem if the opening clause contains two semantic units (I'll underline each unit in the first one):

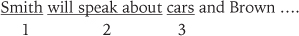

It would be unusual to see a comma here. Similarly with three semantic units:

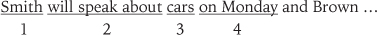

or four:

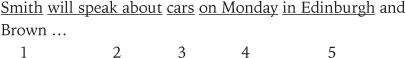

But uncertainty sets in when we get to five:

And if the first sentence gets longer than this, most people will feel the need of a comma.

Note that we can increase the length of the first sentence in other ways, such as by adding adjectives or other forms of modification.

As we reach the âmagic number five', the need to breathe sets in again.

These are adult intuitions. With children, it takes time for their working memories to develop in order to handle such complex sentences. They will therefore be more likely to introduce a comma in places where an adult wouldn't feel it necessary. Teachers who see âtoo many commas' in young writers thus need to be aware that the extra commas may actually be helping them express themselves, as they attempt more complex constructions, and that it takes time to develop a mature comma-using style.

Keep all this in mind as you read the next chapter. Because everything that I've said here in relation to the linking of sentences applies equally when we consider the way commas are used to link constructions lower down the grammatical scale: phrases and words.

25

Commas, the small picture

Grammar always offers us choices. People often ask why grammar is so complex. The answer is simple: because we want to express complex thoughts. If all we wanted to say was âMe Tarzan. You Jane', it wouldn't be complex at all. But we need to do much more than this.

The choices are particularly apparent in a narrative where we string sentences together. We like to vary the way we say things. Only in the simplest early readers do we see repeated constructions:

Peter can see a pig.

Jane can see a horse.

Mummy can see a cow. â¦

The primary options for change occur at sentence ends. So, to return to the example in the previous chapter, when Hilary begins her report about Smith and decides to go for a tightly linked second part, she will use a comma, but what follows can be several grammatical constructions, such as:

Smith is going to speak about cars, and he'll need an hour.

Smith is going to speak about cars, which will need an hour.

Smith is going to speak about cars, needing an hour.

As long as the second construction continues to act as a clause â containing a (finite or non-finite) verb â we need the comma. If we omit it, there's a real chance of ambiguity. In the last sentence above, it's Smith that needs the hour. But in the following version it's the car:

Smith is going to speak about cars needing an hour to warm up before they can be driven at speed.

This is one of the cases where the presence or absence of a comma is nothing at all to do with taste. It depends on what you mean. Do you want to say something more about

cars

or not? If you don't, you'll keep the comma in. If you do, you'll omit it, to show you're thinking about cars in a more specific way.

This ability to be specific or not is a major feature of English grammar, and shows up both in the way we speak (through our intonation) and in the way we write (through punctuation). It can make all the difference in the world. How many sisters does Mary have in this unpunctuated sentence?

my sister who lives in China has sent me a letter

It depends. If we punctuate it like this, she has just one sister:

My sister, who lives in China, has sent me a letter.

If we punctuate it like this, she has an indeterminate number of sisters:

My sister who lives in China has sent me a letter. (My other sister(s) haven't.)

The comma-less clause

who lives in China

makes you think of

sister

in a very specific way. Grammars therefore say such clauses â called

relative clauses

â have a ârestrictive' or âdefining'

function. And when they are surrounded by commas, we see them having a ânon-restrictive' or ânon-defining' function.

The contrast is very frequently used in everyday writing. Again, it can make all the difference in the world. Did John see his parents or not?

John didn't visit his parents, because his brother would be there. (He didn't go.)

John didn't visit his parents because his brother would be there. (He did go, but for some other reason.)

And how did John talk about his relationship with Mary?

He spoke about it naturally. (In a natural way, as if nothing had happened.)

He spoke about it, naturally. (Of course he did.)

This is one of the reasons why people who say âwe can do without the comma' are wrong. For example, in February 2014 the

Mail Online

had an article headed âThe death of the comma?' It was reporting an American linguist, John McWhorter, who was predicting the obsolescence of the comma, on the grounds that you could

take them out of a great deal of modern American texts and you would probably suffer so little loss of clarity that there could even be a case made for not using commas at all.

He seems to have been thinking chiefly of cases like the serial comma, which I discuss in the next chapter, and where clarity is indeed hardly ever affected. But when we consider cases like the distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive, it's clear that abolishing the comma would make us unable to express succinctly and unambiguously an important semantic distinction.

That is the point: succinctly and unambiguously. It would of course be possible to rephrase my sentences about the sisters to avoid having to rely on the punctuation. But why should we do this? The result would be wordier. And it would go against the main reason for having punctuation in the first place: to help represent speech. The contrast between restrictive and non-restrictive is clearly expressed through English intonation, and it's only natural to want to write this down.

These are all cases where the comma has a double function: it separates but it also specifies â expressing a meaning which its absence would not convey. As we look at lower levels of grammatical construction, we see it chiefly having only a separating function. So we wouldn't expect to see it used between the elements of a clause, even if we wanted to pause between them in reading aloud:

The detective in charge of the case / doesn't want to keep on questioning / this new group of witnesses / until the early hours of the morning.

A comma is not used to mark the change-points between subject, verb, object, and adverbial (shown by /). This is one of the big differences between modern punctuation and earlier practice. In Lindley Murray's day, a comma between subject and verb or between verb and object was often used when the element was at all complex. Here are two examples from his

Grammar

:

A conjunction added to the verb, shows the manner of being â¦

These writers assert, that the verb has no variation from the indicative â¦

This would be considered an error today.

The only case which presents a difficulty at this level of grammar is in relation to the optional adverbial. (When I say âoptional', I mean it can be left out without the sentence becoming ungrammatical.) This is a mobile element of structure: it can be used initially, medially, and finally in a clause. So, if we begin with the âbare' sentence

John entered the room

, we can have:

Quickly John entered the room.

John quickly entered the room.

John entered the room quickly.

When the adverbial is short, there's no grammatical or semantic reason to include a comma. The sentences mean the same whether we insert a mark or not:

Quickly, John entered the room.

John, quickly, entered the room.

John entered the room, quickly.

The rhythmical effect is very different, though. So the option is open to any author who imagines these words spoken with a particular pronunciation and who wants to reproduce this effect in writing. Anyone with a penchant for heavy punctuation (often for the pragmatic reason that it it has been hammered into them in school) will of course opt for commas regardless of sentence length or pronunciation. Anyone with a penchant for light pronunciation (often for the equally pragmatic reason that they want their writing to look as uncluttered as possible) will opt for their omission. And there are all kinds of intermediate positions. This is the main domain where âtaste' operates.

But we mustn't ignore semantic factors. A lot depends on the subject-matter. We're more likely to see a comma in a story where the action is proceeding slowly, or where the writer wants to make you think, create a particular atmosphere (of looming menace, of impending doom), slow down the pace, or is simply acting like a camera panning around a view.

Gradually, the first light of dawn illuminated the room.

Equally, the gun may have been in the desk.

Regrettably, you have no future (Mr Bond).

Outside, several children were playing.

We're less likely to see a comma after initial adverbials where the action or the emotion speeds up:

Suddenly a dog barked.

Obviously I'll go with you.

Please don't do anything silly.

If commas are used here, they convey a more dramatic implication, which could be differentially expressed through a dash or ellipsis dots:

Please, don't do anything silly. (A more forceful appeal?)

Please ⦠don't do anything silly. (The speaker is dying?)

Please â don't do anything silly. (The speaker is being authoritative?)

These are of course just some of the many semantic possibilities. And the same considerations influence usage medially and finally:

I think, ideally, you should go.

I don't honestly know.

That's true, geographically.

Come here immediately.

And so we might reflect on the likelihood or otherwise of:

Come here, immediately.

Come here ⦠immediately.

Come here â immediately.

This is where teaching punctuation gets really interesting. I've seen a class of youngsters enthusiastically discussing what would happen if one of these marks were used in a story rather than the others.

It's a really useful teaching exercise, when exploring comma usage, to collect a large number of single-word adverbials like this, and try them out in different contexts â something I haven't got the space to do in this book, where my illustrations have to be selective. When there are no clear-cut rules to guide usage, all we can do is build up an intuition of what good practice is like by reflecting on as many instances as possible. This can come unconsciously just from reading a lot; but the issue can be neatly focused by presenting the learner with a judicious selection of examples.

As the length of the adverbial increases, with phrases and clauses replacing single words, the role of taste diminishes, but the above principles continue to apply. It would be unusual to see commas before short items such as the following:

People took up new jobs afterwards.

People took up new jobs after the war.

Most people took up new jobs after the war was over.

But as the adverbial lengthens, and the number of semantic units in the sentence goes towards the âmagic number seven', we're likely to see a comma:

Most people took up new jobs, after the peace negotiations had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

This is especially so if the first part of the sentence is itself complex:

Thousands of people of all ranks and ages took up new jobs in a wide range of professions, after the peace negotiations had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

And it's virtually obligatory if a medial adverbial goes to such lengths.

Thousands of people of all ranks and ages, after the peace negotiations had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion, took up new jobs in a wide range of professions.

Try reading that without the commas:

Thousands of people of all ranks and ages after the peace negotiations had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion took up new jobs in a wide range of professions.

In all these examples, it's the sentence that counts. That is the âmain unit of sense'. Understanding the whole sentence is the aim. And punctuation helps us achieve that, when sentences are long.

But it's not just a question of length. As with the examples in the previous chapter, the tightness of the semantic relationship between the adverbial and the rest of the sentence is also a factor influencing us in our use of a comma. The tighter the link, the less likely the comma.

John stopped reading the book when the light got so bad he couldn't continue.

This is a very tightly bonded adverbial, as seen by the dependence of

he

and

continue

on what went before. The thought in that adverbial could never stand alone:

The light got so bad he couldn't continue.

But in this next sentence, the link is much looser:

I stopped reading the book, although there was plenty of light in the room.

Here the thought in the adverbial could stand alone.

There was plenty of light in the room.

The comma isn't obligatory, but inserting one certainly helps the reading process, whether internally or reading aloud, and we thus often see it used in such sentences.

The printer John Wilson, in his

Treatise on Grammatical Punctuation

(1844), reflects glumly:

In punctuation there is scarcely any thing so uncertain and varied, as the use or the omission of commas in relation to adverbs and adverbial phrases, when they qualify sentences or clauses.

We can see now why there's such uncertainty. The main cases of divided usage arise when there is a clash between the criteria of length, semantic bonding, and auditory effect. A lengthy construction motivates a comma, whereas a strong semantic link doesn't. This sentence illustrates:

I stopped reading the book about how to carry out an analysis of commas in a wide range of languages(,) when

I realized that it wasn't going to reach any satisfactory conclusion.

Style guides vary in their advice, in such cases. Writers with a strong sense of auditory style are much more likely to use commas, to point the way they want their sentences to be heard. And it's this competition between the criteria that lies behind all the other cases of comma uncertainty, especially the famous âserial comma'.