Making a Point (19 page)

Authors: David Crystal

It's a character note, nonetheless. As it would be for the demon who put the notice on the door to Hell in Pratchett's

Eric

(

You Don't Have To Be âDamned' To Work Here, But It Helps!!!

), eliciting Rincewind's wry comment that I mentioned earlier: âMultiple exclamation marks are a sure sign of a diseased mind.' When we note the way some authors revel in the use of exclamation marks, it's clear that literary usage sends us mixed messages. The Twains and Fitzgeralds of this world are the ones most quoted; but there's another side, when we see these marks used wisely and well. To follow advice that says simply âcut them out' is just plain daft, as it eliminates virtually everything we would ever want to read. And it would put us in a very awkward position as we live our daily lives.

Exclamation marks are unavoidable these days. They litter our roads, warning of danger ahead. They alert us to urgent electronic messages. They appear as an identity mark above a character's head in some video games. And they are there in all sorts of specialized settings, such as mathematics, computer languages, and Internet slang. In phonetics, the mark is a symbol representing an alveolar click sound (as in

tut tut

). In comics, it usually shows a character's surprise or shock, often by the symbol appearing alone in a bubble, in varying sizes (depending on the intensity of the moment). In chess notation, along with the question mark it is part of a family of semantic contrasts:

!

indicates a good move;

!!

a brilliant move;

?!

a dubious move; and

!?

an interesting but risky move.

The exclamation mark can even get into proper names. Places include

Westward Ho!

in Devon and an intriguing family

of names in Quebec: the tiny parish municipality of

Saint-Louis-du-Ha! Ha!

and its local river (

Rivière Ha! Ha!

) and bay (

Baie des Ha! Ha!

) â a

haha

, according to local historians, being an old French word for an unexpected obstacle (presumably encountered when the area was first being explored).

Oklahoma!

has one too, in the name of the musical â though the innovation caught Helene Hanff by surprise. She records, in

Underfoot in Show Business

, how she was working at the Theatre Guild on the press release for the new show, to be called

Oklahoma

. She and a colleague had mimeographed 10,000 sheets when there was a phone call. This is how she tells it:

Joe picked up the phone and we heard him say, âYes, Terry,' and âAll right, dear,' and then he hung up. And then he looked at us, in the dazed way people who worked at the Guild frequently looked at each other.

âThey want,' he said in a faraway voice, âan exclamation point after “Oklahoma.”'

Which is how it happened that, far into the night, Lois and I, bundled in our winter coats, sat in the outer office putting 30,000 exclamation points on 10,000 press releases â¦

Among people, there is a US dance-punk band called

!!! â

pronounced (it would seem from their website) âChk Chk Chk' â a motif that continues in the title of their album

THR!!!ER

, released in 2013. Among individuals, pride of place has surely to go to the writer Elliot S! Maggin, known to enthusiasts of Superman, Batman, and other comics. Maggin recounts the story of his middle initial like this:

I got into the habit of putting exclamation marks at the end of sentences instead of periods because reproduction on pulp paper was so lousy. So once, by accident, when I signed

a script I put the exclamation point after my âS' because I was just used to going to that end of the typewriter at the time. And Julie [his editor, Julius Schwartz] saw it, and before he told me, he goes into the production room and issues a general order that any mention of Elliot Maggin's name will be punctuated with an exclamation mark rather than a period from now on until eternity.

And so it came to pass.

One of the main indications of the ambiguity surrounding the use of the exclamation mark is its overlap with the question mark. It's an ambiguity within grammar as well as punctuation, and in speech as well as writing, reflected in such utterances as âAre you asking me or telling me?' Sometimes the answer is âboth': a person can query and be surprised at the same time. This is what led to the typographical experiment to devise a new combined mark. Martin K Speckter, an adman with a strong personal interest in typography, suggested it in an article in

Type Talks

in 1962. He had noticed that copywriters often used the two marks in the sequences

?!

and

!?

and thought it would be useful to link them into a single symbol ( ). What to call the new mark? Suggestions included âemphaquest', âinterrapoint', âexclarogative', âconsternation mark', âexclamaquest', and other blends, but the one he chose (incorporating an earlier slang term for an exclamation) was

). What to call the new mark? Suggestions included âemphaquest', âinterrapoint', âexclarogative', âconsternation mark', âexclamaquest', and other blends, but the one he chose (incorporating an earlier slang term for an exclamation) was

interrobang

. It attracted a flurry of interest, but not enough to change traditional printing practices, and it largely disappeared from view during the 1970s. However, it is still encountered as a cult usage online, and it even exists as a Unicode character, so it may yet have a future. In the meantime we are left with the two old stalwarts.

Interlude: Inverting exclamation

¡

Innovation in the use of the exclamation mark has a long history. John Wilkins, in his

Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language

(1688), a work that in its detail anticipated Roget's

Thesaurus

, decided that the normal set of punctuation marks wasn't enough to handle all the meanings people want to express. In his view, the main deficiency was in relation to irony:

the distinction of meaning and intention of any words, when they are to be understood by way of Sarcasm or scoff, or in a contrary sense to that which they naturally signifie.

In

Chapter 9

of Part 3, âConcerning Natural Grammar', he observes:

And though there be not (for ought I know) any note designed for this in any of the Instituted Languages, yet that is from their deficiency and imperfection,

and he concludes:

there ought to be some mark for direction, when things are to be so pronounced.

So, in

Chapter 14

, as part of his new writing system, he proposes an inverted exclamation mark. It never caught on, though it has had a recent resurgence online (see

Chapter 33

).

21

Next, question marks?

It's time you went home?

By contrast with its exclamatory cousin, the question mark has attracted little notice over the years. This is because people think it has just one, obvious, semantic function: to show that somebody has asked a question. And they feel that the concept of âasking a question' is so basic and straightforward, so well grounded in English grammar, that uncertainty over its use could never arise. Gertrude Stein held that view (as we'll see at the very end of this book). There isn't even much variation in terminology, over the centuries, apart from an early use of âasker' and a scholarly use of âeroteme' (from a Greek word meaning âquestion'). Everyone seems to have focused on the terms âinterrogation' or âquestion', so we find expressions such as âmark of interrogation', âinterrogative point', and the interesting (but short-lived) nineteenth-century use of âquestion-stop'. Today, âquestion mark' has no competition.

Are people right to think in this way? Is it so straightforward? Yes and no. The main use of the question mark is indeed much more clear-cut than in the case of the exclamation mark. But there are a few complications, partly arising from the imperfect relationship between writing and speech, and partly from the way fashions in English grammatical usage have changed in recent years. Moreover, the changes

seem to be on the increase. So this chapter turns out to be just as long as its predecessor.

What do I mean by âwell grounded in English grammar'? The grammar-books present us with a set of rules that are clear and concise, recognizing the following question-types.

- Yes/no

-questions, as the name suggests, prompt the answer

yes

or

no

(or of course

I don't know

, etc). They're formed by changing the order of the subject and verb:You are going to town. > Are you going to town?

They were ready. > Were they ready? - Wh

-questions (also called

open-ended

questions) begin with a question-word such as

what

,

why

, or

how

, and again change the word-order:What are they doing?

Where did they put the book? - Alternative questions, a sub-type of

yes/no

-questions, present an either/or situation, where the answer can't be

yes

or

no

:Are you awake or asleep?

These question-types rarely present any problems of punctuation. It's been standard practice since the eighteenth century to end them with a question mark, and it would be considered a basic error if one were omitted. Only a very daring literary user gets away with it (such as Gertrude Stein or James Joyce). But some punctuational issues do arise in relation to a fourth question-type.

- The tag question, which can be positive or negative, makes an assertion, and then invites the listener's response to it:

They're going, are they?

They're going, aren't they?

The meanings here are trickier, as they reflect the intonation with which they can be spoken. If I use a rising tone, I'm asking you. If I use a falling tone, I'm telling you.

It's three o'clock, Ãsn't it? (

asking

)It's three o'clock, ìsn't it? (

telling

)

It's this last example that gives us a problem, for if someone is âtelling' us, what need of a question mark? To make the difference between these last two sentences clear in writing, therefore, we will often see this:

It's three o'clock, isn't it? (

asking

)It's three o'clock, isn't it. (

telling

)

or even

It's three o'clock, isn't it!

But the orthographic distinction isn't standard, so that we often have to look carefully at the context to work out which meaning a writer intended, and it isn't always clear. It's one of the pitfalls over the use of the question mark that writers need to be aware of.

Here's another example of the same kind. I saw this request on a classroom door:

Would the last student to leave this room please turn off the light.

This looks like a question, but it has the force of a command. There was no question mark at the end. Should there have been? The force of the request would have been very different if it had read:

Would the last student to leave this room please turn off the light?

This turns it into a genuine question, offering the option of âyes' or âno'. We might interpret such a version in various ways â more inviting, perhaps, or more of a desperate plea! But we don't usually find a question mark in such circumstances. The writer is telling, not asking.

What we're seeing, in these cases, is an echo of the old controversy: does punctuation reflect grammar or pronunciation. The question mark began as a way of giving preachers a useful graphic cue about when to adopt a questioning tone of voice. By the end of the eighteenth century it had been firmly tied to grammatical constructions. Today, punctuation is often used as a way of by-passing grammar and directly representing pronunciations that reflect the intentions lying behind a sentence. It's this pragmatic function that accounts for the asking/telling issue, and it appears again in the commonest contemporary trend: the punctuation of âuptalk'.

You're familiar with uptalk? It's the use of a high rising tone at the end of a statement? As a way of checking that your listener has understood you? The phenomenon began to be noticed during the 1980s, associated chiefly with the speech of young New Zealanders and Australians, and was transmitted to a wider audience through the Australian soap

Neighbours

. At the same time, an American version, associated initially with young Californians (you know?), was being widely encountered through films and television. At first largely confined to young women, it spread to young men, and since has been working its way up the age-range. Although disliked by many, its value lies in its succinctness: it allows someone to make a statement and ask a question at the same time. If I say âI live in Holyhead?', the rising intonation acts as an unspoken question (âDo you know where that is?'). If you know, you will simply nod and let me continue. If you don't, my intonation offers you a chance to get

clarification (âWhere is that, exactly?'). I don't have to spell out the options. Uptalk has also become a fashionable way of establishing rapport, with the intonation offering the other participants in a conversation the chance to intervene.

The feature wasn't new. Several regional accents of the British Isles have long been associated with a rising lilt on statements, especially in the Celtic fringe. That's probably how it got into the antipodean accent in the first place. And there are hints of its presence in earlier centuries. Joshua Steele, in his essay on

The Melody and Measure of Speech

(1775), was the first to transcribe intonational patterns using a musical notation, and he noticed it. It would be very useful, he says, to develop an exact notation to describe âhow much the voice is let down in the conclusion of periods, with respect both to loudness and tone, according to the practice of the best speakers ⦠for I have observed, that many speakers offend in this article; some keeping up their ends too high'. Evidently he didn't like it either.

But, like it or not, statements spoken in a questioning way are here, and so the intention behind them needs to be shown through punctuation whenever people wish to reflect this kind of mutually affirming dialogue in their writing. In the absence of an accepted new punctuation mark to do the job, writers have had to rely on the traditional question mark. We're unlikely to find question marks at the end of statements in written monologues, or in representations of formal conversations; but in places where informality and rapport are the norm, such as Internet chat, they are on the increase. We see messages like these tweets:

I wonder when they'll give an Oscar to an LGBTQ actor for their brave and risky portrayal of a struggling straight person? [lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgendered-questioning]

Maybe we should report weather related brewery closures like the morning TV news reports school closures?

We can imagine the rising tones as these sentences reach their close.

This extended use of the question mark is in fact anticipated in a range of earlier uses expressing such attitudes as uncertainty, doubt, sarcasm, and lack of conviction. The mark is usually placed in parentheses adjacent to (before or after) the word that is its semantic focus:

(a) So I ought to be with you by (?) seven.

(b) This was written by Floura (?) Smith

(c) He claimed that the vote would go our way without any trouble. (?)

(d) She arrived in a new (?) dress.

We have to be careful about mid-sentence placements, as they can be ambiguous. What is being queried in (d), for example: the newness or the dress itself?

The range of meanings is so wide that there's sometimes an overlap with the semantic range conveyed by the exclamation mark. In (a), (b), and (c), replacing the question mark would convey a clearly different meaning:

(c1) This was written by Floura (?) Smith (is that her name?)

(c2) This was written by Floura (!) Smith (what a stupid name)

But in (d), there's hardly any difference, as the ironic intention could be conveyed equally well by either:

(d1) She arrived in a new (?) red dress.

(d2) She arrived in a new (!) red dress.

It's presumably this overlap in meaning that led early typesetters to confuse the two functions when the marks were first used. For example, this is how the First Folio prints one of Hamlet's famous speeches (

Hamlet

2.2.203):

What a piece of worke is a man! how Noble in Reason? how infinite in faculty? â¦

The whole speech is a series of exclamations; Hamlet isn't questioning anything. But apart from the first sentence the printer took everything else as a series of questions.

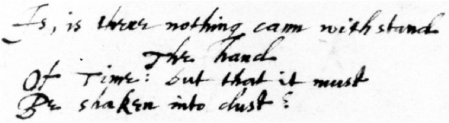

From time to time, people become dissatisfied with the broad application of the question mark and try to narrow it down, usually by proposing distinct marks for the different kinds of question. Rhetorical questions have attracted particular attention, as â not requiring any answer â they are so different in kind. An Elizabethan printer, Henry Denham, was an early advocate, proposing in the 1580s a reversed question mark ( ) for this function, which came to be called a

) for this function, which came to be called a

percontation

mark (from a Latin word meaning a questioning act). Easy enough to handwrite, some late sixteenth-century authors did sporadically use it, such as Robert Herrick. Here are the opening lines of an elegy to his friend John Browne, who died in 1619:

Is, is there nothing cann withstand

The hand

Of Time: but that it must

Be shaken into dust