Making It: Radical Home Ec for a Post-Consumer World (15 page)

Read Making It: Radical Home Ec for a Post-Consumer World Online

Authors: Kelly Coyne,Erik Knutzen

31>

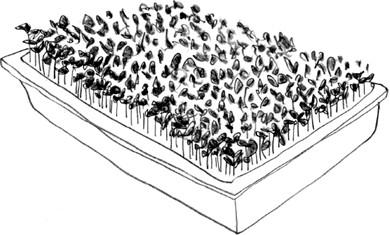

Microgreens

PREPARATION:

30 min

WAITING:

2+ weeks

With a couple of flats, potting mix, and seeds, you can run a real minifarm, indoors or outdoors. Not to be confused with hippie sprouts, microgreens are baby plants—seedlings grown until they produce one or two sets of leaves. Then they are cut to make salads. Their delicate shapes and bright flavors have secured them a place as trendy restaurant fare.

To grow microgreens indoors, you need a sunny, south-facing window. If you don’t have one, you can grow the greens under fluorescent lights. (See Project 48 to learn how to put a grow-light system together.) Microgreens also make ideal patio or balcony crops.

YOU’LL NEED

- Standard 10 x 20-inch seedling flats from a nursery; homemade flats (see Project 56); or, for small batches, clear plastic clamshell containers that hold takeout food

- Clear plastic covers for the flats (Lids are usually sold with nursery flats. Clamshell containers come with lids. For homemade wooden boxes, you’ll need to improvise a plastic lid, perhaps by foraging one from a catering tray.)

- Potting mix

- Seeds (See the lists in the table below.)

PUTTING IT TOGETHER

Make sure the seedling flats have drainage holes—seedlings don’t like wet feet. If a container doesn’t have holes, punch some with a sharp knife. Work very carefully so you don’t split the plastic.

Fill the flats with soil, level it, and compress it ever so lightly.

Sprinkle the seeds over the surface of the soil, about an inch apart. You can mix different kinds of seeds, but choose types that mature at roughly the same time. In the table on page

115

, we’ve divided seed types by growing times. Otherwise, sow different seeds in separate flats. Small seeds should be barely covered with a light sifting of soil. Large seeds, like peas or corn, should be pushed in.

Water gently with a watering can or a hose with a soft sprinkle setting. We like to use a Haws watering can, which has a particularly gentle water flow, perfect for seedlings.

Put the clear plastic cover on each flat. This creates a minigreenhouse where moisture and heat will speed germination. In hot weather, you may need to remove the cover to avoid cooking the microgreens. Watch for signs of wilting.

Keep the soil moist but not too moist. Don’t overwater. If you’re growing seeds in front of a window, turn the flats around every couple of days to keep the plants growing straight. They’ll lean toward the sun.

Harvest no later than the appearance of the first set of true leaves. “True leaves” are leaves that look like miniature versions of the plant’s mature leaves. They are the second pair of leaves a seedling produces. The first set of leaves a seedling produces are called cotyledons. These are rounded, generic-looking leaves. You can harvest after the cotyledons appear or after the development of the first set of true leaves, depending on your preference. How long it takes a seedling to develop two sets of leaves depends on the type of plant you’re growing and the light conditions, but the time frame is usually around 2 weeks. Use scissors to harvest at soil level, as if you were giving your seedlings a haircut. Leave the roots in the soil. Microgreens are best eaten right after harvest, but you can keep them in plastic bags in the fridge for a day or two.

Seed Sources for Microgreens

As you’ll be using a lot of seeds for this project, consider ordering in bulk. Many seed suppliers have sections in their catalogs devoted to microgreens. Health food stores often sell seeds for sprouting, and many of these are good candidates for microgreens. And speaking of health food stores, we’ve even grown microgreens from seeds sold in bulk bins. Surprisingly, we’ve actually had good germination rates with bulk bin seeds, but there are no guarantees. If you have an outdoor garden, you might have leftover seeds from planting. Many of these could be used as microgreen seeds as well.

When the harvest is done, put the roots and spent soil in your compost pile and start again. Clean out the flats for their next go-around. Toss your harvest in a salad or stir-fry and enjoy.

TROUBLESHOOTING

The most likely problem you’ll have growing microgreens indoors is insufficient light. The signs of this are seedlings that become “leggy,” meaning they develop long stems because they’re struggling to reach the light. Leggy seedlings will delay growing leaves or may never reach harvest size. If your seedlings turn leggy, try to find a spot with more light or grow them under fluorescent lights. See Project 48.

If the seeds don’t sprout at all, they may no longer be viable. Seeds have expiration dates. Double-check the package.

For other hints about growing seedlings, see Project 46.

Seed for Microgreens

FAST-GROWING SEEDS

Broccoli

Cabbage

Cilantro

Cress

Endive

Hon tsai tai

Kale

Kohlrabi

Mizuna

Mustard

Pac choi

Radish

Tatsoi

Tokyo Bekana

Waido

Slow-Growing Seeds

Amaranth

Arugula

Basil

Beet

Carrot

Celery

Chard

Ice plant

Komatsuna

Magenta spreen

Orach

Red purslane

Scallion

Shungiku

Sorrel

SEEDS FOUND IN BULK BINS AND ETHNIC MARKETS

Amaranth

Cilantro

Fenugreek

Green chickpea

Mustard

Popcorn

Sunflower

SEEDS THAT FORM EXTRALARGE GREENS, CALLED SHOOTS, THAT ARE USUALLY COOKED

Pea

Popcorn

Sunflower

32>

Sweet Potato Farm

PREPARATION:

10 min

WAITING:

1-2 months

An edible houseplant is an urban farmer’s Holy Grail. Traditional food crops require at least 6 hours of direct sunlight a day, making them tricky to grow inside. Houseplants do well indoors because they are jungle dwellers that have evolved to grow in low light. But they are also prima donnas, expecting you to water, mist, and dust them while offering you nothing in return but their fabulous looks. This rubs against our general gardening rule number one: If you water it, you have to eat it. A worthwhile houseplant would give back—imagine sautÉing a spider plant!—but as far as we knew, no such thing existed. Then, one day, we experienced the Filipino Epiphany.

Our neighbor Julia basically has a Filipino produce section growing in her front yard. One day, we asked her about a nice patch of greens she had going, and she said, “It’s sweet potato. You eat the leaves.” This freaked us out because we erroneously associated sweet potato foliage with potato foliage, which is poisonous. But Julia handed Kelly a leaf and Kelly ate it, because she’ll eat almost anything. It was a tender green with a mild, pleasant flavor.

Turns out that sweet potato greens are indeed a favorite in the Philippines and are eaten throughout Asia and Africa. They’re nutritious, too, rich in vitamins C and A and a good source of calcium and protein. You know what else a sweet potato vine is? A houseplant. A novelty houseplant last popular in the 1970s. We’d found our Holy Grail: a houseplant that feeds you. And because it’s a relative of the morning glory, it’s a good-looking plant, too. It may even flower for you.

YOU’LL NEED

STAGE 1

- At least 1 sweet potato. Organic is better, to be sure the potato hasn’t been treated to prevent it from sprouting. If it’s been around your kitchen a while and has some buds on it, all the better. Just as long as it isn’t withered or moldy.

- A pot/vessel large enough to lay your potato sideways. It doesn’t have to be pretty. It could even be a box lined with a plastic bag.

- Potting soil. Pure sand or peat moss would also work for this first stage.

STAGE 2 (A FEW WEEKS LATER)

- Containers to hold the mature plants. Basically, you can grow a plant in just about anything, from expensive designer ceramics to an old milk jug. These vines would look great in a long trough or in hanging baskets. Just remember that plants need drainage. If your pot doesn’t have a hole in the bottom, drill one. Or put the plant in a plastic nursery pot and tuck that pot inside whatever decorative container you choose. Be sure to put a layer of rocks at the bottom of your pot so the drainage hole doesn’t get clogged.

- Good quality potting soil

PUTTING IT TOGETHER

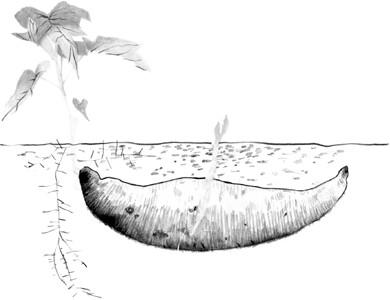

STAGE 1: THE VINE NURSERY

It’s easy to grow a sweet potato vine. All you have to do is bury the tuber under soil, keep it moist, and wait. It will sprout. What we’re going to do here is a little different. We’re going to encourage a potato to send up many sprouts—called “slips”—and transplant those slips to other pots. In this way, one sweet potato will yield many plants. This is important, because to make your sweet potato vines a viable food source, you’re going to need a lot of vines. Otherwise you’ll use up your whole plant in your first stir-fry.

You could opt to just sprout the potato and consider that your finished plant. If so, you’d probably want to plant several potatoes, or halves of potatoes, each in its own pot. That works. The advantage of the transplant method is economy and flexibility. One sweet potato yields many slips, and you can plant those slips anywhere you want.

Yams or Sweet Potatoes?

In the United States and Canada, different varieties of sweet potatoes

(Ipomoea batatas)

are referred to interchangeably as yams and sweet potatoes, with the darker-fleshed ones often being sold as yams. True yams are members of the Dioscoreaceae family—big, starchy things generally found only in Africa and Asia. Any yam/sweet potato you find in the supermarket or farmers’ market in North America, whether it be dark or light skinned, pointy or rounded, will work for this project.

PLANTING THE MOTHER POTATO:

Plant a whole sweet potato lengthwise under 2 inches of soil or sand. That is, you want the sweet potato lying so the long side is facing up. Think of it as a submarine. If there are any buds present, plant them facing up.

Feel free to lay more than one potato in each container, if you can fit them in. Just keep them about 1 inch apart. These potatoes are the mamas that will produce slips for transplanting. The potatoes are planted sideways to maximize the surface area available for sprouting.

Don’t pack down the soil. All you need is a loose covering. Leave a few inches of headroom between the soil and the rim of the pot. This will make watering easier.

Add water. During the sprouting period, keep the soil lightly moist but never soggy. Soggy conditions could cause the potato to rot. The sprouts aren’t killed by lack of water, because they get moisture from the mother potato. It’s better to let the soil go dry than to keep it too wet.

If your house is cold, store your nursery somewhere warm—in the Kitchen, near the radiator, or on top of your electronics. You don’t want to bake the mama potatoes, but they will sprout best if the ambient temperatures are between 70° and 80°F. It may take a long time for the sprouts to appear—even months. It depends entirely on the starting state of the potato. Be patient. If you can’t be patient, gently push the soil away from the potato and check for signs of life. You’ll probably see nubby sprouts and roots forming. Cover up the spud again and go find something else to worry about.

STAGE 2: ESTABLISHING YOUR NEW PLANTS

HARVESTING THE SLIPS:

Rejoice when the first sprouts appear above the soil. They’re ugly at first, but they unfurl into pretty leaves. Let them grow until they have at least three sets of open leaves. Then they’re ready to move.

Gently twist ‘n’ pull the slips off the potato. Yep, just pop them off. They come off with a tiny set of roots attached. Leave the mother potato in the soil. It will keep producing sprouts for you until it has withered down to nothing.

PLANTING THE SLIPS:

How many slips to pot and where to pot them is up to you. It depends on your living situation. For instance, if your only available space is a narrow windowsill, you could line the whole sill with lots of small pots. In that case, you would put one slip in each container. If you have room for a few big pots, you could put several slips in each pot.

This is intensive agriculture. Plant the slips fairly close to each other—much closer than they’d ever be planted out on the farm. Try planting them about 3 inches apart. That would translate to about four slips in a 9-inch pot.

When you plant the slips, bury them up to their chins. In other words, the whole long stem goes under the soil, leaving just the leaves above the soil. That way, each slip will sprout more roots along the stem and make the plant strong. Be sure to leave at least two sets of leaves above the soil. It’s okay to bury the lower sets.

Note:

All this applies to planting your slips in the ground as well. Just remember that sweet potatoes like warmth, so if you’re planting outside, do it during warm months.

CARING FOR THE PLANTS:

Keep the slips moist and be kind to them while they’re rooting and establishing themselves.

Put them somewhere sunny. More sun equals more leaves. If you suspect they’re not getting enough sun indoors, place them under fluorescent lights. (See Project 48.) Potted plants lose nutrients each time you water them, so feed your plants to keep them luxuriant. If you keep a worm bin (Project 61), tea made from worm castings is a fantastic soil supplement. You can buy organic fertilizers at the nursery. Follow the directions on the fertilizer container and feed the slips about once a month.

To keep the plants bushy instead of long and straggly, pinch or cut off the long ends of the vines, making your cut right before the next set of leaves or leaf buds. This will cause side shoots to form.

Like any houseplant, sweet potato vines are subject to common houseplant pests. Spider mites appear on our vines once in a while. These are teeny bugs, just dots to the naked eye. If you notice them, rinse or wipe them off the leaves immediately, and keep checking to make sure no more appear. Simple vigilance should be enough to suppress them within a couple of weeks. Spider mites thrive in dry conditions, so if you mist your plants or rest the plants on trays of wet gravel to increase the local humidity, you may prevent them from ever appearing.

CONTINUING PROPAGATION:

As you eat your plants, you might add more pots to your collection or fill holes in your current pot with new slips. If the mother potato stops offering slips, start a new one. You can also clip small portions of the mature vine and stick them directly in moist soil. They’ll root.

Your indoor plants will never bear potatoes. They won’t get enough light inside to make that big, energetic push. Outdoors, they might develop tubers, but you must have a long growing season—roughly 100 frost-free days.

HOW TO EAT THEM:

The leaves and the stem bits attached to the leaves are the best parts to eat. The newest shoots are the most tender. Prepare these as you’d prepare spinach or any green.

Herbal Medicine and Beauty

Some of the most common culinary herbs, like rosemary, sage, and peppermint, have potent healing properties. This dual nature has made them beloved garden mainstays for centuries. Other traditional healing plants, like chickweed, plantain, and yarrow, grow wild and are considered weeds. The following projects highlight the uses of these plants in homemade medicines and beauty products. It’s well worth growing a few herbs in your garden or learning to forage beneficial weeds around the neighborhood. If that’s not possible, you can always buy herbs in bulk at health food stores or online.