Male Sex Work and Society (40 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

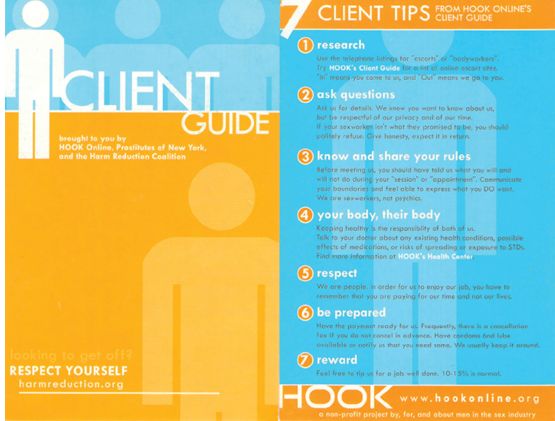

FIGURE 8.2

“Client Guide,” a handout from HOOK Online, a major U.S. Internet-based health advocacy organization for male sex workers. Reprinted with permission from HOOK Online,

www.hookonline.org

.

www.hookonline.org

.

Nevertheless, quite early in the HIV epidemic, sex workers of both genders came to be viewed as a threat to public health. In his book,

The Origins of AIDS

, Jacques Pepin (2011) provides an excellent description of the social (e.g., 1:10 ratio of women to men in early European colonial towns in West Africa that promoted prostitution and polyandry) and economic (e.g., no “female” jobs) dynamics that inadvertently helped spread HIV through heterosexual sex work and sex trading. As HIV in the developed world was first identified among men having sex with men, the leap was made that male sex workers were spreading HIV without any direct evidence.

The Origins of AIDS

, Jacques Pepin (2011) provides an excellent description of the social (e.g., 1:10 ratio of women to men in early European colonial towns in West Africa that promoted prostitution and polyandry) and economic (e.g., no “female” jobs) dynamics that inadvertently helped spread HIV through heterosexual sex work and sex trading. As HIV in the developed world was first identified among men having sex with men, the leap was made that male sex workers were spreading HIV without any direct evidence.

The first wave of research reported the prevalence of HIV among samples of MSWs (Bimbi, 2007; Minichiello et al., 2013) as a means to demonstrate the “threat” these men posed to the health and welfare of the larger public. Specifically, MSWs were argued to be “a vector for transmission of HIV infection into the heterosexual world” (Morse, Simon, Osofsky, Balson, & Gaumer, 1991). However, when reporting the prevalence of HIV among samples of MSWs, the authors did not include (perhaps the data were not available) the corresponding prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the same geographic area (e.g., “20% of our MSW sample reported being HIV positive which is similar to the prevalence rate of all MSM in our area”). Therefore, absent a comparison, MSWs are portrayed as spreading HIV due the presence of HIV positive men in a research sample.

The “Typhoid Harry” stigma (Koken et al., 2004) labels sex workers as vindictive and uncaring about the risk of spreading infection to their clients; what is forgotten is that when unprotected sex does occur, it is typically in response to client pressure or coercion (Jamel, 2011), not the sex worker’s willful intent or cavalier attitude about unprotected sex (Bimbi & Parsons, 2005; Parsons, Koken, & Bimbi, 2004). There seems to be wide consensus among male (and female) sex workers in most wealthy nations that condom use is part of the job (Browne & Minichiello, 1997; Parsons et al., 2004). Some researchers have found that this has had the unintended effect of MSWs eschewing condoms when having sex for their own pleasure (Allman & Myers, 1999; Weber et al., 2001), as condoms become associated with work. It also could be that the observed high number of sex work partners may be related to increased rates of “safe sex burnout” (Bimbi, 2007). In comparison, sex workers in developing nations and poor sex workers overall report lower rates of condom use with clients (Pisani, 2008). Sex workers, regardless of venue, often must deal with clients offering more money for sex without condoms. There also are structural constraints on MSWs using condoms. As with female sex workers, male sex workers, out of fear of being arrested for “providing evidence of prostitution,” may not carry condoms (Allman & Myers, 1999; Morse, Simon, & Burchfiel, 1999). There has been some organized pushback against this law enforcement practice from sex worker advocates and sex worker organizations. In New York State, for example, there have been repeated (failed) attempts to pass legislation that bans police from this practice, most recently in 2012 (Kloppot, 2012). This is a clear contradiction between state-funded public health programs that distribute free condoms and the criminal justice system (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

The risk behavior that does occur with clients may result from negative attitudes toward condoms and a lack of knowledge about HIV transmission (Minichiello et al., 2000), as well as a perceived (lack of) susceptibility to HIV (Simon, Morse, Balson, Osofsky, & Gaumer, 1993). A perceived lack of control in interactions with clients may also lead to unprotected sex (Joffe & Dockrell, 1995; Morse et al., 1999; Simon et al., 1993). As gay and bisexual men who desire men themselves, MSWs may be tempted to engage in unprotected sex with clients they find attractive, which is known as “heaven trade” (Browne & Minichiello, 1995; DeGraaf, Vanwesenbeeck, Van Zessen, Straver, & Visser, 1994; Joffe & Dockrell, 1995; Simon et al., 1993; Smith & Seal, 2008). Repeat clients and clients who become familiar with a male sex worker may also build a sense of trust (Davies & Feldman, 1997) or a longing for intimacy (“the single blues”; Joffe & Dockrell, 1995; Smith & Seal, 2007), which may lead to sexual risk-taking.

Aside from burnout or other psychological factors, behavioral and situational factors such as injection drug use have been shown to be related to MSWs having unprotected sex with casual partners (Bower, 1990; Williams et al., 2003). Several studies have suggested that MSWs may be more at risk for contracting or transmitting HIV through needle sharing than unsafe sex (Elifson, Boles, & Sweat, 1993; Estep Waldorf, & Marotta, 1992; Waldorf & Murphy, 1990; Waldorf, Murphy, Lauderback, Reinarman, & Marotta, 1990). Nevertheless, it has been reported repeatedly that, in samples of gay men in developed countries, drugs popular with the gay scene, particularly nitrate inhalants (“poppers”) and stimulant drugs or those with similar effects (crack, methamphetamine; Mimiaga, Reisner, Tinsley, Mayer, & Safren, 2009), are strongly associated with having unprotected sex. Therefore, drug use “on the job” may lead to having unprotected sex with clients. Many clients (and this also applies to those hiring female sex workers) often want to “party” with the sex worker and arrive at arranged meetings already drunk or high on drugs. Some gay MSWs who are involved with the party scene may view “free” drugs provided by the client as a bonus.

On the other hand, MSWs who are uncomfortable about their work may use drugs or alcohol to numb their feelings while with clients (Bimbi, Parsons, Halkitis, & Kelleher, 2001; Mimiaga et al., 2009). Straight-identified men in particular may use drugs to deal with the threat to their identity that results from engaging in same-sex behaviors (Bimbi, 2007). Men both gay and straight who are dependent on alcohol or drugs may exchange sex for drugs, or engage in sex work only to pay for drugs (McCabe et al., 2011; Mimiaga et al., 2009). Regardless of motivation or etiology, substance misuse among male sex workers is clearly a phenomenon that needs more attention and program development. (See

chapter 9

for a further discussion on substance use among MSWs.)

chapter 9

for a further discussion on substance use among MSWs.)

While identifying risk factors clearly is important in public health, factors that promote protection and condom use should not be overlooked. As advertising for sex has mostly moved online, away from restrictions imposed on print classified ads, sex workers are free to be as sexually explicit or expressive as they want, although they may purposely avoid “quid pro quo” statements about the exchange of sex for money. It is quite common to see the phrase “payment is for my time only” in such ads. Many male sex workers directly promote safety on their Internet profiles by including statements such as “safe sex only” and state their own HIV status or employ euphemisms such as “healthy” or “disease free.” Some may not state anything about health status or protective practices, and there are far fewer who explicitly advertise for barebacking (sex without condoms).

Some argue that the online milieu for sex work is conducive to more open and honest sexual negotiation (Minichiello et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2004). MSWs themselves have also reported feeling responsible for initiating condom use and practicing universal precautions (Minichiello, Mariño, & Browne, 2001; Parsons et al., 2004). For many, condoms have become part of their “work equipment” (Bimbi, 2007; Parsons et al., 2004; Smith & Seal, 2008). In fact, there may be no negotiation at all, as the sex worker may introduce the condom as part of foreplay, avoid penetrative anal sex, trick the client by putting on a condom orally, or simply end the session and walk out.

Recommendations

It does appear that gay-identified MSWs are at high risk for HIV infection, due to factors related to their same-sex attractions and involvement with gay subcultures (e.g., the party scene), as well as through recreational drug use, regardless of sexual identity or orientation. Although there are clear public health needs among MSWs and their clients, evidence-based recommendations for practice and policy are sorely lacking. Fortunately, sex worker advocates have filled in those gaps, and there is enough consensus in the evidence to inform broader polices for program and service development that could be implemented within existing indigenous governance systems. Before implementation, however, structural barriers must be addressed. The WHO (2012) official recommendations to improve the health and well-being of sex workers (regardless of gender) include the following as the foundation for programs and services:

1. All countries should work to decriminalize sex work and eliminate the unjust application of non-criminal laws and regulations against sex workers.

2. Governments should establish anti-discrimination and other rights-respecting laws to protect against discrimination and violence, and other rights violations sex workers face, in order to realize their human rights and reduce their vulnerability to HIV infection and the impact of AIDS. Anti-discrimination laws and regulations should guarantee sex workers’ right to social, health, and financial services.

3. Health services should be made available, accessible, and acceptable to sex workers, based on the principles of avoiding stigma, non-discrimination, and the right to good health.

4. Violence against sex workers puts them at risk for HIV and must be addressed in partnership with sex workers and the organizations they lead.

FIGURE 8.3

Front cover of a pamphlet issued by the European Network Male Prostitution, which is aimed at service providers in Switzerland to promote sexual health programs for male sex workers. Copyright © ENMP/Swiss AIDS Federation

The WHO also explicitly recommends the following interventions to enhance community empowerment among sex workers:

• Voluntary HIV testing and counseling for sex workers

• Anti-retroviral therapy for HIV-positive sex workers

• Correct and consistent condom use among sex workers and their clients

• Strategies to reduce harm to sex workers who inject drugs

• Including sex workers in catch-up hepatitis immunization strategies for sex workers who didn’t receive these immunizations in infancy

Obviously, any interventions should deal competently with gay culture(s) and sex work culture(s) by building partnerships with local gay and sex work communities, specifically with businesses that cater to these populations, and with nongovernmental organizations and health-care providers. Cultural competency and community partnerships are essential to successful implementation.

Implementation

If the above recommendations answer what to do and for whom, putting those recommendations into practice asks where, when, and how. When implementing programs and attempting to draw MSWs in, we must address who the target is and what we are trying to accomplish. This will require developing different service levels or program content based on the differing needs of sex workers (e.g., housing, counseling), with the specific goal of improving health and wellness. No one program can be all things to all types of sex workers, so providers must be knowledgeable about other services to which they can refer them when necessary. To cast the widest net and reach as many sex workers as possible, outreach efforts should be tailored for broad audiences, such as all men who have sex with men (the population approach), and for targeted audiences, such as men who sell and buy sex (the community approach).

Other books

Detective Partners by Hopkins, Kate

The Dollmaker by Stevens, Amanda

Nine Buck's Row by Jennifer Wilde

Bombs Away by Harry Turtledove

A Way in the World by Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul

Never Any End to Paris by Enrique Vila-Matas

The City Who Fought by Anne McCaffrey, S. M. Stirling

The Map and the Territory by Michel Houellebecq

Vengeance by Jarkko Sipila

Montbryce Next Generation 03 - Dance of Love by Anna Markland