Map of a Nation (24 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

From childhood, Zachariah’s second son Thomas (William’s uncle)

exhibited

‘strong indications of mechanical genius’. As a teenager, he was apprenticed to a famous London watchmaker and showed sufficient talent to set up his own business. Soon Thomas Mudge was making clocks and watches for King Ferdinand VI of Spain. Where Zachariah was said to be ‘very fond of that method of philosophizing’ that prioritised the general idea over individual detail, his son was instead transfixed by the mechanical

minutiae

of timekeepers. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, Thomas threw himself into a dispute that split the scientific community in two.

Back in 1714, a governmental body had been established ‘for the Discovery of Longitude at Sea’. Longitude and latitude, those conceptual lines that criss-cross the globe, were the primary means by which mariners oriented their vessels. Latitude was easy to discover according to the height of the sun or various stars above the horizon. But in the eighteenth century longitude was much trickier to establish on board ship. There were two principal ways: because the earth turns on its own axis every twenty-four hours, the sun’s light shifts longitudinally as time passes and therefore a calculation of the time difference between the boat and the home port allows the

determination

of the distance between them in longitude. Proponents of a technique known as the ‘chronometer method’ of discovering longitude suggested that if a mariner could carry a clock set to the time of the home port, the time difference between the port and the ship could be simply discovered. Advocates of the alternative ‘lunar distance method’ of determining longitude used the moon as a clock from which sailors could derive the time on board ship. By consulting a volume of ‘lunar tables’, they could then discover the time over in Greenwich and derive the longitudinal difference between the two locations. But there were serious problems with both methods. There were

neither

lunar-distance tables nor chronometers accurate enough to cope with this task: the rolling of a ship, changes in temperature or variations in air pressure played havoc with the rate of timekeepers. So in 1714 the Board of Longitude set up a competition that offered a prize of

£

20,000 to anyone who could determine longitude on board ship to within thirty nautical miles of accuracy.

Famously a man called John Harrison, who had built his first clock in 1713 at the age of twenty, dedicated himself to the chronometer method of

overcoming the longitude problem for over forty years. Between 1730 and the 1770s, this talented craftsmen made five beautiful timekeepers for the competition, for which he eventually received a total of

£

23,065. Harrison’s payment was not won without a battle. Britain’s Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne was passionately supportive of the lunar-distance method. He worried, with some justification, that even if a supremely precise and reliable chronometer was constructed, it would be impossible to mass-produce such a minutely accurate instrument cheaply enough to allow every mariner in the world to benefit. Maskelyne was a prominent member of the Board of Longitude, and his sometimes combative insistence on the thorough testing of Harrison’s timekeepers and his general scepticism about the

chronometer

method has been well documented (often in ways that malign the astronomer’s reasonable doubts as snobbery).

When Harrison died in 1776 it was William Mudge’s uncle Thomas who picked up the baton. Harrison had produced unprecedentedly accurate chronometers but there still remained much room for improvement: his clocks were found to become unreliable over a period of years. In the mid 1770s Thomas Mudge produced three timekeepers for the longitude competition and over the next decade these were subjected to numerous trials under Maskelyne’s watchful eye. Although Mudge’s chronometers proved much more accurate in the long term than Harrison’s, he too became infuriated by the astronomer’s apparent attempts to thwart his success and

withhold

remuneration. His eldest son Thomas Mudge Junior was a lawyer and in 1793 he fought for his father’s case to be brought before Parliament, with support from the prominent Whig William Windham, the Hungarian astronomer Francis Xavier Baron de Zach and Admiral John Campbell. But Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and an influential member of the Board of Longitude, was strongly opposed to Mudge’s efforts to claim the prize. He flatly rejected the superiority of Mudge’s timekeepers and protested that a financial reward would ‘discourage the advancement of knowledge, or check the spirits of emulation among artists, by neglecting those who have a superior, and rewarding others who have an inferior, claim to patronage and liberality’. A parliamentary committee was established to look into the case and eventually awarded Thomas Mudge the relatively

modest sum of

£

2500. He died two years later, but his son continued to fight on behalf of him and his timekeepers, publishing pamphlets and establishing a factory to show how the chronometers were suitable for mass-production (which proved unsuccessful).

In the first years of William Mudge’s employment on the Ordnance Survey, the name of ‘Mudge’ was firmly associated in the public consciousness with the longitude conundrum, and also with the antagonism with the Astronomer Royal and the nation’s foremost scientific institution, the Royal Society, both prominent supporters of British surveying. Probably for these reasons William Mudge remained notably reticent about the spat between his uncle and cousin, and Banks and Maskelyne. When the furore had died down, he inserted a brief aside into a published article that commended Thomas Mudge’s

chronometers

: a small mark of family loyalty. If William Mudge had inherited his grandfather’s ability to see the big picture, then his uncle Thomas gave him the means to temper it with an eye for detail. William enjoyed clock-making as a hobby and was delighted when the King of Denmark presented him in 1819 with a gold chronometer as an award for his achievements. But it was his father and his father’s friends who arguably played the greatest role in William Mudge’s development and helped him to foster a kind tolerance and quiet humour, and an eloquent love of literature and art.

W

ILLIAM

M

UDGE’S FATHER

John had grown up in Plympton St Maurice, a pretty village north-east of Plymouth that is overlooked by a ruined motte-and-bailey castle. (The Mudges’ presence in Plympton is now commemorated by a busy thoroughfare called ‘Mudge Way’.) John Mudge had found his headteacher at Plympton Grammar an inspirational presence. Samuel Reynolds had a number of hobby-horses, among them medicine and astrology. In one class he terrified and enthused his students by

presenting

them with a human skull for examination; and he was frequently spotted star-gazing among the ruined turrets of Plympton Castle. An apocryphal and distressing anecdote recounts how, using astrological observations to calculate

his children’s horoscopes, Samuel was appalled to discover that his young daughter, Theophila ‘Offy’ Reynolds, was faced with ‘very great danger’ around her fifth birthday. When that time came, the story goes that Samuel forbade his daughter to leave the house and took ‘every precaution’ to ensure her safety. But ‘at the very time predicted’, Offy’s nurse was walking by an open window on the top floor of the house and accidentally let the child slip from her arms. Offy plummeted through the window to her death.

Samuel Reynolds also had a son called Joshua, a short, stocky young boy with a ruddy complexion, rounded cheeks and a slight harelip. Only two years John Mudge’s junior, the two boys formed a close friendship during their time at Plympton Grammar. But while John hung, entranced, on his teacher’s descriptions of gruesome medical ailments, Joshua’s schoolbooks were crammed with sketches and architectural plans. By the age of eight, he had taught himself the rudiments of perspective and was often found outside rather than inside his classroom, drawing ‘the schoolhouse according to rule’. He was an avid fan of his schoolfriend’s father’s sermons, and later it was said of Joshua that he owed ‘his first disposition to generalize, and to view things in the abstract, to old Mr Mudge’. In his teens, Joshua found himself torn between a career as a general practitioner in medicine and chasing his artistic ambitions. Reasoning that if he were only destined to be ‘an

ordinary

painter’ then he would rather follow a medical career, Joshua made up his mind to become a

great

artist.

And so he did. After an apprenticeship to one of the principal portrait painters in Britain, Joshua Reynolds set up his own practice. By 1748 the press was hailing him as one of the youngest of fifty-seven best ‘painters of our own nation now living’. Despite his drawling Devonshire accent, his ‘coarse’ features, ‘slovenly’ dress and a hunger for gambling, Joshua became one of the most sought-after portraitists in mid-eighteenth-century Britain. He was the hub of a vibrant intellectual circle that included the

lexicographer

Samuel Johnson, the politician Edmund Burke, the actor David Garrick and the poet and playwright Oliver Goldsmith. When King George III granted his ‘gracious assistance, patronage, and protection’ towards the founding of a Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, Joshua was elected its first president. Four months later he became Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Throughout this meteoric rise to fame, Joshua remained close to his Devonshire family and friends. Various portraits testify to his ongoing

friendship

with the Mudges. His old childhood companion John Mudge pursued the career in medicine that Joshua had himself rejected. John trained at the nearby Plymouth Hospital, becoming a distinguished doctor who specialised in the treatment of smallpox and respiratory illnesses: ‘Mudge’s Inhalers’ were popular chemists’ items. When in 1752 Joshua found himself suffering a period of poor health, on return from a trip to the continent he travelled to Devon to consult John and gratefully painted the doctor’s portrait while he was there. A few years later, John’s eldest son was employed in the Navy Office in London. Unwell on his sixteenth birthday, the young boy was so upset at having to forgo his intended celebratory trip home that Joshua

sympathetically

reassured him with the promise ‘Never mind! I will send you to your father!’ He painted a portrait of the boy peeping out from behind a curtain and sent this to John Mudge in place of his son.

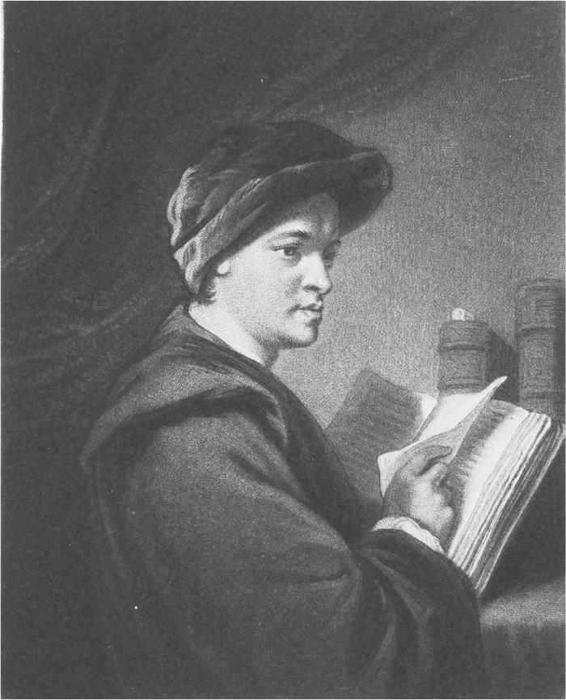

20. John Mudge, by Samuel William Reynolds, after Joshua Reynolds, 1838 (1752).

By the late summer of 1762, John Mudge had remarried after the death of his first wife. When his second wife Jane was heavily pregnant with her second child (William), Joshua decided to pay a visit to his old schoolfriend and the now elderly Zachariah Mudge, and he brought along his good friend Samuel Johnson. On 31 August, the pair arrived at John’s Plymouth home, where they stayed for almost four weeks. Joshua painted John’s

portrait

again and the group made excursions to local friends and landmarks, including the newly reconstructed lighthouse on the treacherous Eddystone Rocks, fourteen or so miles offshore from Plymouth: one of the shining achievements of John Mudge’s friend, the civil engineer John Smeaton. Samuel Johnson’s distinctive physical appearance and idiosyncratic

behaviour

startled many of the Mudges’ associates. A towering six feet tall, his body riddled by convulsions, with poor eyesight and hearing, sudden grunts, erratic head-rolling and a face disfigured by scrofula, Johnson’s mannerisms – combined with his ‘excesses in new honey, new cider, and clouted cream, at one of the Devonshire tables’ – were said to ‘alarm his entertainer[s] much’. John Mudge and Joshua Reynolds took Samuel Johnson to meet Zachariah Mudge and hear him preach. Rumour has it that, on returning to Zachariah’s vicarage after the sermon, the Mudges offered Johnson afternoon tea.

Blissfully

innocent of the polymath’s enormous appetite, when he presented his cup for an eighteenth helping, Zachariah’s wife exclaimed ‘What! Another, Dr Johnson?!’ ‘Madam, you are rude,’ he retorted.