Map of a Nation (26 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

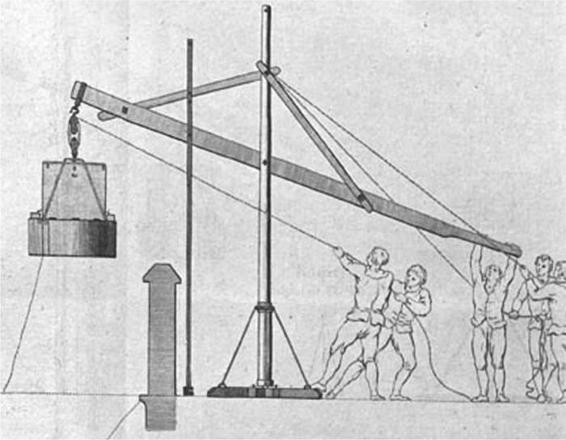

The national triangulation began in the spring of 1792. Mudge had decided to tack the new Trigonometrical Survey onto the triangles that Roy had created during the Paris–Greenwich triangulation, and to progress west from there. (For this reason, the commencement of that earlier project in 1783 is often suggested by map historians to be the real beginning of the Ordnance Survey.) At both ends of the baseline, portable scaffolding was erected to a height of thirty-two feet, to the top of which the 200-pound theodolite was precariously winched by a crane manoeuvred by five or so

artillerymen. Mudge then gingerly inched his way up a ladder to the

observation

platform at the top of the scaffolding. The instrument was protected from the weather by a canvas canopy, but Mudge was not so lucky. Surveying from this great height in a high wind, which caused the scaffold to sway alarmingly, must have been nerve-racking. Even the sight of the landscape through the sights of such a sophisticated theodolite was dizzying. In an instant, the panorama before Mudge’s eyes disappeared and was replaced by an enlarged image of a minute portion of land, magnified almost beyond imagination and bisected by a grid of wires that helped to pinpoint an exact spot. The experience was like swapping the eye back and forth between a small-scale map of the nation and a large-scale estate survey. Right at the beginning of the eighteenth century the philosopher George Berkeley had described the strange effect of switching one’s gaze from normal, unassisted eyesight to that provided by a lens. ‘The same object’ is not ‘perceived by the microscope, which was by the naked eye,’ he claimed.

22. A team of men lifting the 200-pound theodolite using a crane.

But soon Mudge had got the hang of his theodolite and his sight lines were

ricocheting from the two ends of the Hounslow Heath baseline to St. Ann’s Hill in Chertsey; to Banstead Church spire in the north-eastern corner of Surrey where it now merges into Greater London; to Shooter’s Hill near Greenwich, one of the capital’s highest points; to Bagshot Heath in

north-west

Surrey; to a tower on Leith Hill, in mid Surrey; to the chalky summit of Butser Hill, one of the highest points in Hampshire; and finally down to Rook’s Hill, a few miles west of Charles Lennox’s mansion at Goodwood in West Sussex. Up in his eyrie at the top of the scaffolding, Mudge jotted down in a small bound notebook the angles of his horizontal and vertical

observations

, the date, the exact time and even the temperature of the air, probably using either a goose quill pen or one of the new metal pens whose nibs did not require constant sharpening and were particularly useful

outdoors

.

Mudge also needed to measure the relative heights of the trig points, and he did so by a process called ‘levelling’. A spirit level was used to provide the position of a sight line that travelled horizontally from a ‘levelling telescope’ at trig station A. Trig station B was at a different height from A, say fifty feet higher, and there a surveyor manipulated a ‘levelling rod’ (a staff marked with measurements of length) so that it dropped vertically towards the

horizontal

sight line from A. The observer at that first trig point noted where the vertical rod met the telescope’s horizontal sight line, and used the rod’s measurements to ascertain the vertical difference between the two trig points. In May 1793 Mudge used this levelling method to ascertain the height of a trig station at Dunnose, on the Isle of Wight, above the low-water mark. Using a spirit level, he positioned a telescope (on an instrument called a ‘transit’) on the horizontal from the trig point and trained it towards the coast at Shanklin. There his assistants used a measuring tape and rods, which they positioned vertically up a cliff face, to discover the 792-foot

vertical

distance that separated the height of the trig station from ‘the water’s edge’. Over longer distances, levelling could be done trigonometrically. The theodolite’s telescope could be trained from one trig point to another at a different height, and the angle that separated the telescope from the

horizontal

could be used in a trigonometric equation to determine the vertical distance between them.

Mudge was not the only one to be transfixed by the eminently mappable qualities of the landscape of southern England. In 1793 the local poet Charlotte Smith described its ‘boundless, yet distinct’ hills that spread out before her ‘even as a map’. After a spell in London the American author John Neal wrote in 1830 of the breathlessness that was triggered by the view from ‘the top of a great hill (such as Leith Hill) with an empire lying under [its] feet like a map’. Eighty-five years later the mystic poet James Rhoades imagined this same view spread out ‘like a map’ before two observers who were elevated above it like map-makers:

Where Leith Hill tower the landscape crowns,

And points a stony finger,

On Sussex, Surrey, Kent, the Downs,

Our eyes have loved to linger.

From Reigate round to Shoreham Gap

We’ve marked the spires up-peeping,

Fields, hamlets, hedgerows, like a map,

In mellow sunlight sleeping.

Thanks to the Ordnance Survey, the landscape that these writers compared to a map became the subject of a real survey.

Once Mudge, Williams and Dalby had completed the observations from the two ends of the Hounslow Heath baseline, they began to move south through Sussex. With the assistance of men from the Royal Artillery, the Ordnance Survey’s instruments and papers were transported from trig point to trig point by road, in carriages and on horseback. The Great Theodolite was given its own ‘spring waggon’ with improved suspension ‘to preserve it from injury’. The Sussex coastline is a varied stretch of land, on which beaches are backgrounded by impressive ruined castles and high grasses are interspersed with wetlands and play home to a variety of birdlife. But the Ordnance surveyors’ first experiences of the county were likely to have been unpleasant. The thoroughfares south of London, especially in Sussex, were notorious. Constant traffic churned their surfaces into mud and it was

said that because of this mire ‘respectable Sussex women went to church in ox-drawn coaches, and Sussex men and animals had grown long-legged through pulling their feet through the clay’. Horace Walpole warned a friend: ‘if you love good roads … be so kind as never to go into Sussex’ as ‘the whole country has a Saxon air, and the inhabitants are savage’.

William Mudge and his colleagues carried out their observations in the morning and evening, ‘when the air was free from vapour, and without that quivering motion, which, in summer, it generally has in the middle of the day’. They followed the standard annual surveying pattern that had been adopted by the Military Surveyors before them: late spring, summer and early autumn were spent ‘in the field’. Late autumn to early spring were spent back at headquarters, processing the calculations. To protect the Great Theodolite from adverse weather, it was housed in a portable observatory: an octagonal tent with windows through which its telescopes surveyed the surrounding scenes. This observatory, according to a surveyor, ‘consisted primarily of an internal skeleton of eight iron pillars, bound together by oak braces, and supporting a roof consisting of eight rafters united together at the top, and clamped at the bottom to the iron pillars. The sides and roof were composed of frames covered with painted canvas, and the whole

covered

with a strong tent.’ Wherever the theodolite went, so did its shelter. When the Ordnance Survey turned its attention to hillier ground, the

additional

weight of the iron and oak frame and the canvas covering would prove an excrutiating burden to carry up peaks and over the uneven ground of moors and heaths.

Many of the coastal landmarks on which Mudge trained the theodolite’s sights as it travelled further south were old signal stations. Crowborough Beacon in East Sussex, Penn Beacon on Dartmoor and Ditchling Beacon on the South Downs were all part of a historic, now redundant network of warning stations. When one beacon flared in the distance, the next was lit by watchful residents, and that was seen by the next settlement along, who in turn lit their beacon, and so on. In event of an emergency this alarm system could transmit intelligence of a crisis or invasion from coast to capital. As each beacon was distant yet clearly visible from the next, they made ideal trig points for the Ordnance Survey’s triangulation.

In the Survey’s early days, Williams, Mudge and Dalby decided to

illuminate

their surveying staffs at the trig points with lamps, just as Roy and Cassini had done during the cross-Channel observations of the Paris–Greenwich triangulation. Lamps effectively illuminated the

surveying

staffs over long distances or through hazy weather. The map-makers commissioned three such lanterns from a ‘Mr Howard of Old-Street’, and they consisted of flares and reflectors inside ‘strong tin cases, having plates of ground glass in their fronts, which effectually prevented the bad effects of an unequal and unsteady light’. These lamps were ‘found to equal everything which could be expected from them’ and the largest, which had a diameter of twenty-two inches, ‘was lighted on Shooter’s Hill, and [was] clearly distinguished at the distance of 30 miles’. But as these lanterns were lit beside the south coast’s warning beacons, many locals interpreted the flares as signals of French invasion. In April 1793 the

Sussex Weekly Advertiser

was forced to reassure its readers that ‘a General Survey of the Kingdom being now carr[ied] on by Government’ would necessarily involve the use of ‘White Lights’ at several stations along the south coast. The journalist explained that the surveyors’ lights could be easily distinguished from emergency flares ‘by their peculiar brilliancy, and short duration, which will not exceed four or five minutes’. The

Gazetteer

also had to assure the inhabitants of Ditchling that ‘they need be under no alarm for the visits lately paid them by some of the Artillery’, who were only ‘making a trigonometrical survey of this county’.

L

ATE IN THE

summer of 1792, Mudge, Dalby and Williams found

themselves

camped beside the trig point at Hindhead in the thickly wooded south-western corner of Surrey. On the outskirts of the breathtaking

geological

scoop known as the Devil’s Punch Bowl, the best view of the surrounding landscape and the most apt location for a trig point was

positioned

‘22 feet north-west’ of a gibbet. In this spooky spot, the surveyors received a letter from Charles Lennox, the Master-General of the Board of Ordnance, with a command that altered the entire remit of the project:

Lennox wanted to begin fleshing out the Trigonometrical Survey into a map. He commanded Mudge to ‘furnish Mr Gardner, chief Draftsman to the Board of Ordnance, with materials for [making] a Map’ of Sussex, which Lennox emphasised was ‘intended, at some future period, to be

published

’.

The Board of Ordnance boasted its own map-making department in the Drawing Room of the Tower of London, which was quite separate from the Ordnance Survey. These draughtsmen were civilians, not military men, and since 1787 they had been co-directed by Lennox’s old estate surveyor William Gardner. Now Lennox had come up with the idea of reinvigorating the ‘Great Map’ of Sussex that Gardner and Lennox’s other estate

surveyor

, the late Thomas Yeakell, had begun in the mid 1780s. Only four out of eight projected sheets had originally been published and Lennox decided that it was time to fill out the triangulation into a full map by completing the Sussex survey and conforming the initial measurements to those provided by Mudge’s Trigonometrical Survey. Williams and Mudge had previously

entertained

the possibility, perhaps reluctantly, that map-makers from outside the Ordnance might use their triangulation to make maps. But now Lennox was recommending that the Board of Ordnance itself should be responsible for such an achievement.