Map of a Nation (3 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

The same deficiencies hampered the soldiers in their pursuit of the rebels in the battle’s aftermath. Charged with policing the country that Scott had found so difficult to negotiate, Major General John Campbell had

commented

: ‘by the Map of the country it appears very easy & a short cutt to cross over from Appin by the end of Lismore to Strontian’. In reality, this required island-hopping across Loch Linnhe, followed by a lengthy pathless scramble over the steep rocky overhangs and mountain streams that

punctuate

the scrubby cluster of hills south-east of Strontian. No wonder Campbell had concluded that, contrary to the map’s advice, ‘I have had [the route] viewed and it is impracticable in every respect.’

The problems caused by these poor maps were aggravated by the extreme inaccessibility of the country in which many of the rebels were hiding. The soldiers complained of ‘the Want of Roads … the Want of Accommodation, the supposed Ferocity of the Inhabitants, and the

Difference of Language’. Official reports warned that other parts of the Highlands were ‘extensive, full of rugged, rocky mountains, having a

multiplicity

of Cavities, & a great part of these cover’d with wood & brush. The places are of difficult access, thro’ narrow passes, & most adapted of any to concealment of all kinds.’ A newspaper gloomily confirmed that ‘there are Hiding-places enough’. Furthermore, the Highlanders’ superior intelligence networks always seemed to be one step ahead of the soldiers. These networks extended north, south, east and west, giving advance warning of the soldiers’ approach to fugitive rebels. One of the King’s officers noted that ‘our Detachments have always been betrayed by People that the Rebels had on the top of the High Hills, who by some Signall agreed on could always convey any Intelligence from one to another in a short space of time’. Conversely the redcoats found that their own ‘Intelligence [was] very

difficult

to obtain, notwithstanding Promises of reward & recommendation of Mercy’.

Because of the Hanoverian troops’ lack of good geographical intelligence in the face of such complicated scenery, Lord Lovat, a partially crippled near-octogenarian, was able to evade them for almost two months. He was eventually caught in the second week of June, when a division of redcoats towed their own boat over the peninsula that separated Loch Morar from the sea and rowed to his island. There they found ‘that wily old Villain’ hiding in a hollow tree, betrayed only by a glimpse of tartan through a chink in the trunk. Most of Lovat’s followers had already dispersed, melting into the surrounding mountains like ghosts. The redcoats’ Commander-

in-Chief

, the Duke of Cumberland, was intensely relieved: ‘The taking [of] Lord Lovat is a greater Humiliation & Vexation to the Highlanders than any thing that could have happened,’ he wrote jubilantly. ‘They thought it

impossible

for any one to be taken, who had these [mountainous] Recesses open, as well known to him to retire to.’

Greatly enfeebled by his flight, Lovat was carried on a litter to Fort William at the southern end of the Great Glen, then to Fort Augustus at its heart and finally to the Tower of London. On 18 March 1747 he was found guilty of high treason for the second time in his life. But this time there was no escape. On 9 April Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, chief of

Clan Fraser, was executed, earning the dubious accolade of being the last person in Britain to be publicly beheaded. Meanwhile, the ‘burning scent’ of the Young Pretender had gone stone cold. Despite the assertion of one Hanoverian commander that ‘I should with infinite Pleasure walk barefoot from Pole to Pole’ to find him, Charles Edward Stuart had been able to secrete himself away in Scotland’s western islands, before finally securing a voyage home to Italy, and safety.

T

HE PERIOD THAT

Lord Lovat spent in hiding from the King’s troops marks a pivotal moment in the history of the nation’s maps. It became unavoidably clear that the country lacked a good map of itself. Britain had national maps, but prior to the eighteenth century they had served a mostly symbolic function. When, in 1579, Christopher Saxton had published the first atlas of England and Wales, almost every sheet of his thirty-five maps was adorned with Elizabeth I’s arms: Saxton’s surveys were royalist insignia. Just over thirty years later, William Camden published the first English

translation

of his

Britannia

, in which his aim was overtly nationalistic. Camden wanted to celebrate ‘the glory of the British name’ by ‘restor[ing] antiquity to Britaine, and Britaine to his antiquity’, and his book’s elaborately engraved frontispiece displayed a map surrounded by ancient icons of British patriotism, such as Stonehenge, to encapsulate this joined love of country and history. In 1610 John Speed had presented a county atlas to Britain’s map-reading public, whose opening pages offered an exquisite, highly coloured map of ‘Great Britaine and Ireland’ beneath a coat of arms. An image of London in the top-right corner was balanced with one of Edinburgh in the top left, hinting perhaps at a convivial relationship between these capitals.

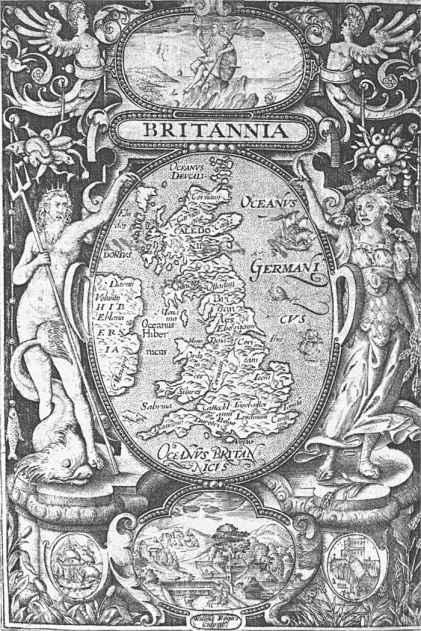

1. The frontispiece to the 1600 edition of William Camden’s

Britannia.

Although many early modern national maps were potent emblems of power, control, ownership and nationalism, their accuracy was often highly questionable. Surveys of nations were rarely made by measuring the ground itself, which was a time-consuming, skilled and expensive process. Instead,

map-makers tended to amalgamate information from a host of pre-existing maps to produce ‘new’ surveys, inevitably leading to the replication of old errors. And even when early surveyors did conduct their own

measurements

, many of their instruments and practices were the cause of further errors. The telescope was only invented at the beginning of the seventeenth century and it was not used at all in surveying instruments until 1670, which meant that map-makers’ observations were restricted by the capabilities of their naked eyesight. After 1670 until around the middle of the eighteenth century, telescopic lenses were still liable to cause problems in the form of ‘chromatic aberration’, incongruous fringes of colour resulting from the lenses’ failure to focus all colours to the same point. Accuracy in early map-making was further compromised by the susceptibility of many

surveying

instruments’ materials to changes in temperature, which made them expand and contract. Chronometers and clocks had a frustrating tendency to speed up, slow down or stop altogether. And the measuring scales with which instruments were engraved were not sufficiently minute for a high level of accuracy, and mathematicians possessed no agreed method with which to reconcile conflicting results. Different maps of an identical piece of land could therefore look very dissimilar, and although estate maps were generally reliable enough for their owners’ purposes, over larger areas errors proliferated. In 1734 a map-maker called John Cowley superimposed six existing maps of Scotland, and in doing so he created a striking image of radical divergence and disagreement. Some early map-makers did not even pretend to aspire to perfect truth and accuracy. The seventeenth-century Czech engraver Wenceslaus Hollar provided a telling admission of the limitations of early methods when he inscribed this motto onto one of his maps of London: ‘The Scale’s but small, Expect not truth in all.’

The 1745 Jacobite Rebellion vividly revealed the lack of, and need for, a complete and accurate map of the whole island of Britain. Over the next one hundred years, the myopia that had left Lovat’s pursuers groping in the faintest of half-lights would lift agonisingly slowly until, at long last, Britons would be able to carry in their mind’s eye, or in their pockets, a full and truthful image of the nation in which they lived.

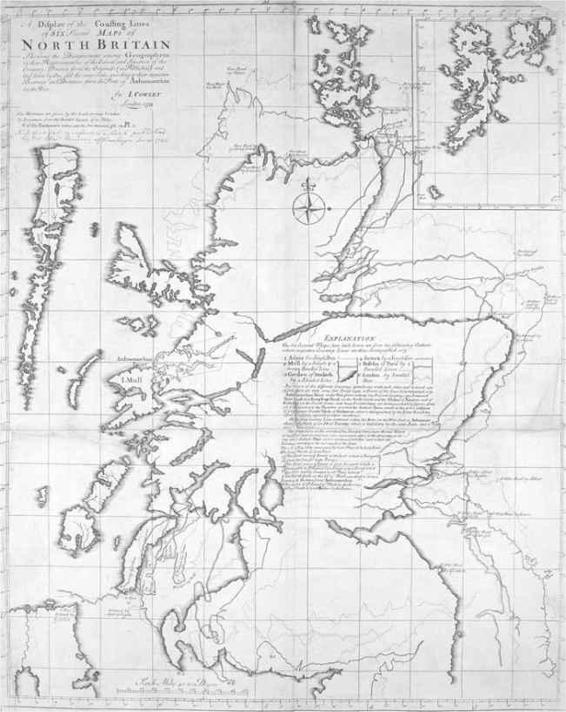

2. A Display of the Coasting Lines of Six Several Maps of North Britain,

compiled by John Cowley in 1734, and revealing the severe discrepancies between early-eighteenth-century maps of Scotland.

The story that follows is an account of how, why and where Britain’s national mapping agency came into being. Today the Ordnance Survey is easy to take for granted. From the Shetland Isles in the furthest north-easterly reaches of Britain,

to Penzance and the Scilly Isles in the south-west, it has surveyed every mile of the nation, dividing it into a cubist jigsaw of overlapping sheets. Today the Ordnance Survey’s

Explorer

series covers Britain in 403 maps, and the

Landranger

series in 204. Each region, however inaccessible and forbidding, however urban and congested, possesses its own highly detailed map on a range of scales and with near-perfect accuracy. These surveys intimately trace the course of all the roads, national trails, minor footpaths, bridleways, power cables, becks, gills, streams, brooks and field boundaries that bisect a landscape of miniature woods, speckled scree slopes and orange contour lines. Black and blue icons represent sites of public interest, ranging from public toilets and telephones to National Trust properties and ancient ruins. In addition to its folded maps, the Ordnance Survey is also the source of the information contained in many A–Z street atlases, road maps, and walking and tourist guides published in the United Kingdom. Its depictions of the landscape fill the screens of ‘satnavs’ and

similar

hand-held navigational devices. The Ordnance Survey’s massive digital database, the OS Master-Map, provides geographical data to a host of hungry consumers: national and local governments, transport organisations, the

Army and Navy, the emergency services, the National Health Service, housing associations, architects and insurance companies.

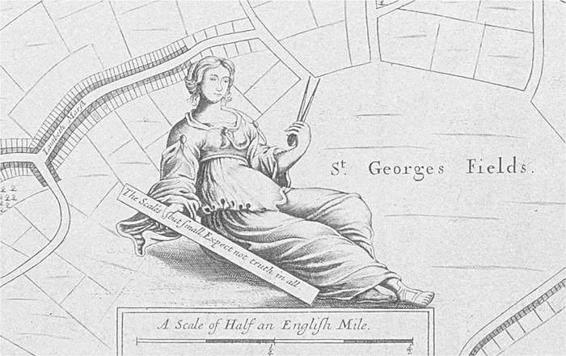

3. A detail from

A New Map of the Cittyes of London and Westminster,

published around 1680 and attributed to Wenceslaus

Hollar.

The national mapping agency has established a secure place in the

affections

of the modern British public. Ramblers lovingly fold dog-eared maps into plastic wallets to protect them from the country’s soggy climate. Hikers become cheerily infuriated when the maps, like the nation’s newspapers, refuse to crease cleanly at the required section and flap as capriciously as kites in sudden gusts of wind. At home, outspread across a carpet or table, OS maps display Britain’s landscape in such vivid and exact detail that walkers can conjure in their imagination the course of eagerly anticipated or fondly remembered hikes, translating contours into visionary mountains and thin black lines into fantastical drystone walls. And the Ordnance Survey has left traces of its remarkable undertaking in the very landscape it mapped. Triangulation stations, or ‘trig points’, are those squat concrete pillars that hunker down amid rocks, heather or grass in the nation’s most panoramic spots, precisely marking the points at which the OS’s

map-makers

placed their instruments. There are over five thousand in England alone, and trig points have become an obsession in their own right: members of the United Kingdom’s ‘Trigpointing Community’ hunt after the pillars like prey. They have been described as one of the most beloved ‘icons of England’.