Map of a Nation (6 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

For the senior officers involved in computation and advanced scientific techniques, its day-to-day work was mentally stimulating and could offer opportunities for travel across Great Britain, Europe, America, Canada and sometimes even further afield. Engineers had no choice but to roll up their sleeves and ‘get their hands dirty’, so the Corps often attracted those to whom practical work and fresh air were more important than dignity and reputation. It was a small operation and places were extremely limited, so prospective engineers with influential personal connections like David Watson exploited their advantage to the full.

A

FTER ATTAINING

a sought-after place in the Corps of Engineers, David Watson was delighted to find himself posted to Flanders in June 1743 to support King George II’s troops in the War of the Austrian Succession.

Now in middle age, nearly forty years old, Watson was buoyant. He boasted a tall, athletic frame, large watchful eyes, a geometrically pleasing profile and a neat, determined mouth. Confident of his own abilities, and at ease in the presence of power, Watson achieved a degree of fame in Flanders by

helping

the King and his 25-year-old son William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, achieve a resounding victory against the French at the Battle of Dettingen. The Secretary of State for Scotland’s private secretary reported excitedly that, although ‘we do not live in an age, or in a land of Heros’, nonetheless ‘Mr Watson has gained universal character in Flanders’. But Watson’s sojourn did not last long.

When the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion broke out, military commanders were initially reluctant to move soldiers deployed on the Continent back to Britain. But as Charles Edward Stuart’s army penetrated deeper into England, one panicky diplomat emphasised the severity of the situation. ‘The Pretender’s son [has] near 3,000 rebels with new arms and French louis d’ors,’ he angrily pointed out. ‘We have not above 1,500 men [and] I cannot but wish for the return [of the army] without which I am certain we do not sleep in whole skins. Our danger is near and immediate, all our defence at a distance … I bewilder myself in scenes of misery to come, unless

providentially

prevented.’ So in autumn 1745 the British troops were finally recalled to fight the Jacobites on home territory and David Watson was among them.

4

. Col. David Watson on the Survey of Scotland,

1748, by Paul Sandby.

As the Jacobites retreated north, the King’s soldiers followed in pursuit. Watson’s commander, the Duke of Cumberland, offered him the role of Quartermaster General, which placed Watson in charge of army

provisions

. The winter of 1745 was bitterly cold and he was responsible for locating sufficient quantities of ‘warm Jackets’, adequate blankets, tents and new shoes for the rapidly moving troops. The Jacobite Rebellion convinced Watson that the rebels were aberrations, whose actions jeopardised ‘the happyness this poor Country enjoy’d before the late irruption of these Barbarians’. And in the wake of what he termed ‘our Interview with the Rebels upon Coloden Moor’, he became something of a Hanoverian hero, due to the ardour with which he rooted out Charles Edward Stuart’s

surviving

followers. Watson was a superficially charming man, at ease in his tall

soldier’s physique and possessed of a biting wit. His letters openly admitted the ‘temptations of pleasure or game’ that he found in the ‘hunt’ after the Jacobites, especially in pursuit of the prize prey of Lord Lovat and the Young Pretender. Watson engineered ‘the destruction of the Ancient Seat of the Glengarry’ clan and was sardonically confident that ‘the rest of the good people of Lochaber’ who witnessed that violence will ‘remember the Rebellion in the Year 46’. He was adamant that ‘the Highlanders [are] the most despicable enemy that ever Troops mett with’.

Once the immediate brutality was over, Watson dedicated himself over the months that followed to ‘the sole motive of restoring quiet, by convincing the World that Rebellion and its Authors are to be come at in the most

inaccessable

parts of the Highlands’. He was among a number of government sympathisers who applied themselves to a long-term programme of Highland reform. Together with his brother-in-law Robert Dundas, and Dundas’s son Robin, Watson formulated strategies to systematically

suppress

Jacobite support, to destroy the loyalty that bound the clans together, to undermine Highland identity and to rebuild the region’s infrastructure, driven by the ambition of unifying a hitherto divided Scotland and

eradicating

Jacobitism once and for all. Like many, the three considered the Highlands to be ‘lawless’ and ‘barbaric’ regions, whose clan system kept individual citizens in thrall to their chiefs, cowed beneath robberies, assaults and threats from neighbouring clans. In 1707 the Anglo-Scottish Union had constitutionally united England and Scotland into ‘Great Britain’, but it had only really succeeded in cementing sympathies between Lowland Scotland and England. The Highlands, with its autonomous legal system, language and culture, continued to be almost a separate nation.

Watson and the Dundases were not by any means the only ones who

proposed

practical strategies to ‘pacify’ the Highlands in the wake of the rebellion. Suggestions from others included the disarming of the clans, the establishment of soldiers to police the region, the building of better roads and the confiscation of Jacobite estates ‘for the purposes of civilizing, and promoting the happiness of the Inhabitants upon the said Estate … by

promoting

amongst them the Protestant Religion, good Government, good Husbandry, Industry and Manufactures’. Many considered that the

Highland landscape was responsible for its inhabitants’ rebellious

behaviour

. Mountains and lochs formed natural barriers between clans, fostering a profound sense of community and dividing Highlanders from Lowland

influence

. One man felt that Highland chiefs were mirrors of their surroundings in more metaphorical ways too: both were useless, obstructive and terrifying. ‘Such

Noble-men

as these are like

Barren Mountains

, that bear neither Plants nor Grass for Publick Use,’ he wrote. ‘They touch the Skie, but are unprofitable to the Earth.’ Based on this assumption, Watson’s voice was heard, over and over again, passionately and articulately asserting ‘the Benefit [which] must arise from protecting the Highlands by the Regular Troops’ and the need to ‘acquir[e] a perfect knowledge of the Country’. Watson particularly sought to remedy the deficiency of geographical information about the Highlands under which the King’s army had suffered before, during and after the ‘Forty-Five’. Watson pointed out that his colleagues had ‘found themselves greatly embarassed for want of a proper Survey of the Country’ and he emphasised the vital need for a good map of Scotland to facilitate the

opening

up of hitherto inaccessible areas of the Highlands.

Watson voiced his concerns persuasively to his commander, the Duke of Cumberland, who took the matter to his father, King George II. It was later reported that ‘the Inconvenience was perceived and the Resolution taken, for making a Compleat and accurate Survey of Scotland’. But Watson had no intention of trying to execute such a mission himself. Instead, he turned to a man over twenty years younger: a man with no evidence of formal training in map-making and apparently no history of military involvement. It was a curious choice, but it would prove inspired.

T

HE

U

PPER

W

ARD

of Lanarkshire is a quiet region, composed of tightly wooded dells and lush fields. In the seventeenth century these

tranquil

slopes were the scene of violent clashes over the doctrine and organisation of the Scottish Church. Walter Scott’s novel

Old Mortality

depicted a Lanarkshire whose ‘broken glades’ and ‘bare hills of dark heath’

had been as dreadfully rent by those civil wars as by the ancient geological upheavals that, millennia earlier, had created the ‘windings of the majestic Clyde’. In the wake of this century of turmoil, on 4 May 1726, a boy called William was born to Mary Stewart and her husband John Roy. Since the mid seventeenth century William Roy’s grandfather and then his father had been employed at the estates of Hallcraig and Milton in the Upper Ward. These lands were owned first by Sir William Gordon, the father of Robert Dundas’s wife Ann Gordon, and then by Ann’s brother, a rather

obstreporous

lawyer called Charles Hamilton Gordon. The Roys lived in a small cottage on these estates’ southern border called Miltonhead. This building and the estates’ two mansions have since disappeared and the land now houses the Carluke Golf Club and, until fairly recently, an intricate Gothic mansion called Milton-Lockhart, which was the sometime home of Walter Scott’s son-in-law and biographer, John Gibson Lockhart.

1

The Roys were factors – land-stewards – and they managed the practical upkeep of the estates. An early-eighteenth-century guide to ‘the Duty and Office of a Land Steward’ described the many responsibilities of this position, which ranged from the relatively menial, such as trapping pests and catching poachers, to more onerous duties such as collecting tenants’ rents, preventing subletting and ensuring the land was adequately farmed. Surveying was a vital part of the jobs of Roy’s father and grandfather. ‘It is necessary,’ wrote one contemporary land-steward, ‘to know the quantity and quality of every parcel of land belonging to his lord’s estate’, and to do so he advised that the factor ‘should have a correct map of the whole … in which map, should be expressed every bend, corner, and irregular turn in the several hedges; all rivers, bridges, highways, gates, and stiles’. Other manuals to the

landsteward’s

role emphasised that ‘it is not only necessary that a Steward should be a good Accomptant, but also that he should have a tolerable Degree of Skill in

Mathematicks

, Surveying, Mechanicks, and Architecture’.

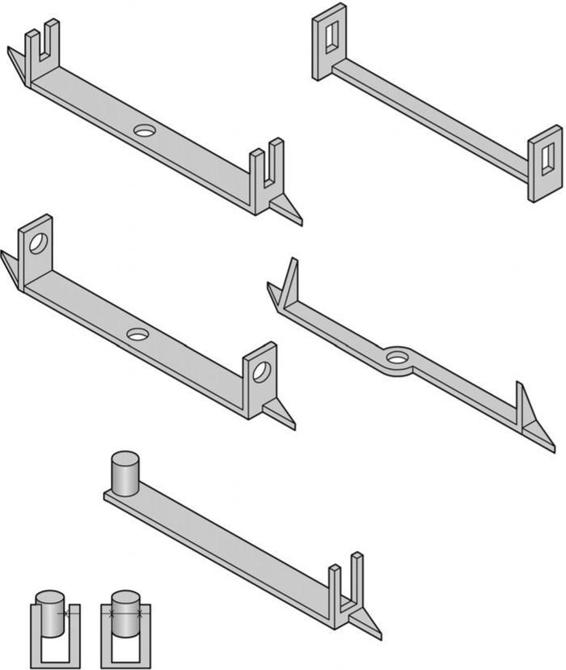

5. Alidades.