Map of a Nation (46 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

On 9 May 1825 the

Derry Journal

noted that five officers ‘with a

detachment

of the royal sappers and miners, have arrived in this city, to commence the survey of Ireland’. Three months later, the Irish

Examiner

related the news that ‘Major Colby, Director of the Ordnance Survey, left the Tower [of London] last month, for the inspection of the … survey of Ireland.’ After establishing ‘head-quarters of his detachments, each under the command of a Captain of Engineers’ at Antrim, Coleraine, Derry and Dungarvon, Colby proceeded to Divis Mountain, on the outskirts of Belfast. Under the Ministry of Defence’s control between 1953 and 2005, when it was handed to the National Trust, Divis provided the British military with a valuable vantage point over Belfast during the Troubles. The same panoramic opportunities made the mountain invaluable to the Ordnance Survey in the nineteenth century. From Divis, Colby could see with his naked eye to the Mourne Mountains in County Down, to Hollywood in County Wicklow, and to the Sperrin Mountains, which stretched from Lough Neagh in County Tyrone to the south of County Londonderry. More importantly for the Ordnance Survey’s purposes, Colby could also see as far as Scotland, to the mountains of Merrick, in Galloway, to Goat Fell on the Isle of Arran and Tartevil on Islay, and to South Berule on the Isle of Man. These long cross-sea

observations

that were theoretically available from Divis and other similarly prominent peaks like Ulster’s highest mountain, Slieve Donard, meant that the Ordnance Survey’s triangulation in Ireland could be joined on to the Trigonometrical Survey of the British mainland.

But the Irish weather made such long sight lines from Ireland to Britain very difficult to attain. Colby was plagued by ‘inveterate haze and fogginess’ on Ireland’s east coast, which obstructed and sometimes entirely thwarted his observations. A journalist for the

Belfast News Letter

described his attempts to

observe from Slieve Donard in 1826: ‘the weather has been extremely adverse to the operations of the gentlemen employed in this arduous task for some time past. For nearly a fortnight the mountain has been so constantly enveloped in mist, that it has been impracticable to do any thing.’ The writer hoped that the map-makers’ perseverance will ‘stand proof against the obstacles of the weather’, and he reminded his readers that ‘while we enjoy calm weather and sunshine in the regions below, they exist in a constant gale, and [are] enveloped in clouds[,] and might, with great propriety, be … denominated the Children of the Mist’.

A relatively new surveyor among these ‘Children of the Mist’ came up with an innovative solution to the relentless cloud and fog. During his time at the University of Edinburgh, Thomas Drummond had developed an aptitude for mathematics, natural philosophy and chemistry such that his tutor felt that ‘no young man has ever come under my charge with a happier disposition or more promising talents’. Long conversations with Colby had persuaded the young man that the military might provide fruitful

opportunities

to develop his scientific interests. Although he disliked the Army’s inflexible discipline, in the early 1820s Drummond was glad to find himself a trained military engineer on his mentor’s Irish surveying team. He was an obsessively hard-working officer. Refusing to leave hilltop stations during the most fiendish storms, Drummond regularly contracted severe chills, colds and influenza, and frequently had to take sick leave as a result. When his boss’s endeavours to observe with the theodolite from Ireland into England and Scotland were foiled by thick fog, Drummond applied his

scientific

nous to the problem. He took two recent inventions and developed them to meet the Ordnance Survey’s needs.

The heliostat or heliotrope, deriving from the Greek

helios

, sun, was a

surveyors

’ device, originally devised by the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, that used a mirror to reflect the sun’s rays to illuminate a distant station. An article about its invention in the

Gentleman’s Magazine

reported how the heliostat could be ‘of great importance’ to map-makers ‘in the measuring of large triangles’. Attracted by this potential application, Drummond tinkered with Gauss’s invention, adapting the heliostat so it could be attached to a theodolite rather than a telescope, and making it

smaller, lighter, more portable and much easier to adjust. But it was the development of the limelight that made Drummond’s name. Invented in the 1820s by the chemist Sir Goldsworthy Gurney, this worked by placing a small globule of lime carbonate ‘shaped into the form of a boy’s marble, and about three-eighths of an inch in diameter’ in a spirit lamp, where it was ignited and burned with magnesium in the midst of ‘a stream of oxygen gas’. The resulting bright white flame was harnessed in a reflector that

produced

rays vastly more dazzling than existing flares. One witness reported how ‘the brilliance of the light thus produced is so intense, that it is quite impossible to survey it, and like the sun it produces that painful sensation upon the retina, which renders it necessary to avert the eye almost instantly’.

The limelight was sometimes called the ‘pea light’ after the small, green appearance of the tiny globe of lime. When Drummond witnessed a demonstration by the chemist Michael Faraday, he became instantly excited. Drummond foresaw that such a flare could be used to illuminate distant

signals

through dark or foggy weather and he began promoting the limelight, publishing articles in the Royal Society’s journal and arranging public demonstrations. One such display took place in a darkened 300-foot-long hall in the Tower of London, where the limelight was lit beside two

competitors

, the Argand burner and the Fresnel lamp, which had both been used previously by the Ordnance Survey in Britain. A spectator reported that Drummond’s invention was so ‘overpowering, and as it were, annihilating both its predecessors, which appeared by its side, … [that] a shout of

triumph

and admiration burst from all present’. Another commented that the Fresnel lamp ‘is like the moon, compared with the brilliancy of the sun, when placed beside the pea light’. By the 1830s, the instrument was

popularly

known as the ‘Drummond Light’ and in 1837 it made its first theatrical appearance, illuminating the stage of the Covent Garden Theatre.

The Ordnance Survey used these products of Drummond’s remarkable imagination to penetrate Ireland’s ‘inveterate haze and fogginess’. The

limelight

was first used to conduct observations over the sixty-seven-mile distance that separated Divis from Slieve Snaght, in County Donegal. On 28 October 1825, Drummond ascended the pyramidal form of the latter, which reached above 2000 feet, and set up his tent and a surrounding wall ‘so that we may

consider ourselves safe against any storm’. But the weather was atrocious. Fog quickly gave way to ‘a storm of snow’ and Drummond wrote on 4 November that ‘my tent is blown [down] and I now write from a kind of Cave, formed on the lee side of the Hill’. Nevertheless, he valiantly

continued

to light the limelight and manipulate the heliostat at the times that he had agreed with Colby, who was perched on the summit of Divis, training his theodolite on Slieve Snaght and scanning the horizon for the telltale flare. In those days prior to telephones and radios, Drummond had no idea whether his limelight was visible from Divis and personally ‘despair[ed] of success; there must be a hill in the way’. But on 12 November an officer on Divis gave Drummond

a very hurried intimation of our having seen the reflector. I have still greater pleasure in communicating the result of the light, it was most brilliant. In the evening, when preparing for our observations, one of the watch called out that there was a much stronger light than the one at Randalstown and a little above it; we immediately turned to that direction and there we saw the light; it was most brilliant, exceeding in intensity any of the Light Houses … These two days’ observations have completely established the advantage of this admirable

invention

… the light … can be very easily intersected from its steadiness and brilliancy.

In August 1826, Colby attempted what was then the longest

trigonometrical

observation ever made, between Slieve Donard and the mountain of Scafell in the Lake District, the highest peak in England. Poised at Slieve Donard’s summit and 2785 feet above sea level, Colby swept the easterly horizon with the theodolite’s telescope. Alighting on a hazy shadow behind the northern point of the Isle of Man, he sharpened the telescope’s focus, adjusting its vertical position with his right hand and agonisingly slowly pushing it around on its horizontal axis with his maimed left arm. As he focused the lens even further, Scafell, which was a staggering 111 miles away, gradually materialised at the centre. Shaking with excitement, Colby prepared himself to read the horizontal and vertical angles off the

theodolite

. But at that moment an assistant officer barged into the tent, demanding Colby’s attention. Accidentally striking the map-maker’s elbow, he jolted

the theodolite out of position. Scafell disappeared from the telescope, like the prey vanishing from the sights of a gun. It was said that only ‘a momentary ejaculation of anger escaped [Colby’s] lips’. Successfully reining in his hot temper, he quickly regained equanimity and, ‘though he could not again

succeed

, and the object was, therefore, lost, he never afterwards alluded to the subject’.

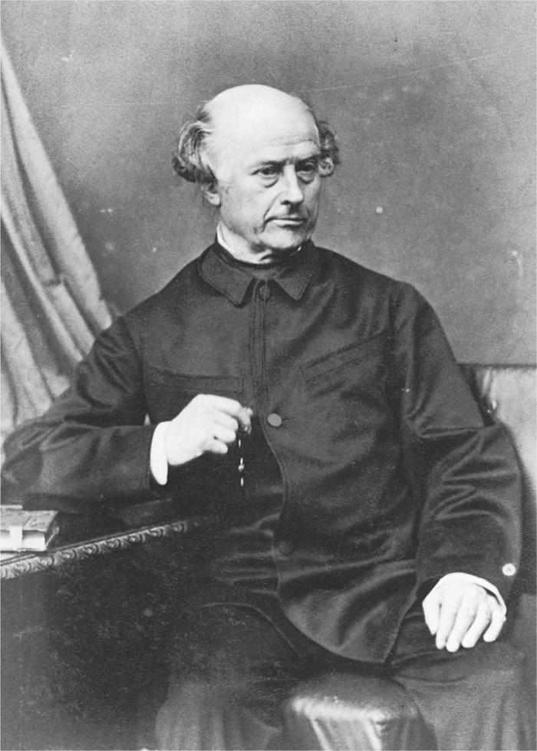

C

OLBY DID NOT

like Ireland much at first. He proclaimed that he did not want to become ‘buried’ or ‘bottled up’ in Dublin and continued to travel back and forth to Britain. He appointed numerous assistants to ease his workload, including a man called Major William Reid as his resident deputy. And he also made a wise choice in the employment of a 24-year-old second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, who originally hailed from Hampshire, called Thomas Aiskew Larcom. Stocky and rather short, with a wide brow and quizzical expression, Larcom had been selected by Colby from among the Corps’ new recruits. He counterbalanced his superior’s hot-headedness with a cool and organised mind, and Colby’s passion for the outdoors with his own relish for more cerebral things like numbers,

calculations

and statistics. The two men made a wonderfully complementary team.

The scale of the Irish map was six times larger and more detailed than that of the one-inch British surveys, and such an expansive scale demanded exceptional accuracy from the Interior Surveyors. The Ordnance Survey in Britain had set a pattern whereby an initial triangulation was followed by the detailed interior mapping, but an English officer pointed out that in Ireland there were tangible advantages in commencing the Interior Survey

before

the triangulation had got under way. He suggested that if the Interior Surveyors were unable to fudge their measurements to conform to those already

discovered

by the Trigonometrical Survey, their integrity and skill would be truly revealed, and the maps’ accuracy would be brought up to the level required by such a large scale. The Irish map-maker William Edgeworth stepped in and suggested that the triangulation should be commenced

immediately, but that its results could be withheld from the Interior Surveyors to achieve the same effect. These discussions, in which Colby was closely involved, significantly delayed the triangulation’s progress, so the Interior Surveyors had in practice no choice but to proceed with their work without the trigonometrical results.

34. Photographic portrait of Thomas Aiskew Larcom, by Camille Silvy, 1866.

Both the Interior and the Trigonometrical Surveyors were faced with

hostility

from local residents as they made their way across Ireland. Dressed in military uniform, the men were unmistakable emblems of British

occupation

. A surveyor in the parish of Drumachose in County Derry reported: