March Toward the Thunder (18 page)

Read March Toward the Thunder Online

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

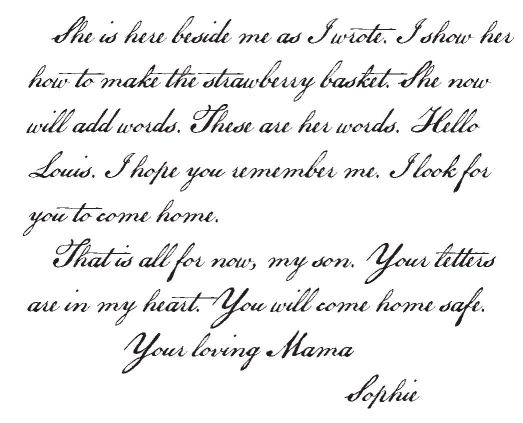

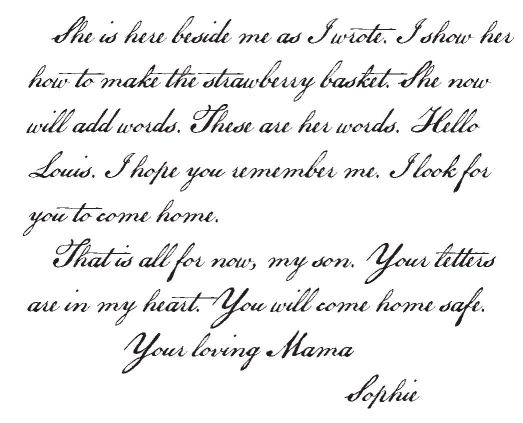

Then more of her everyday voice crept in.

Louis sighed at the thought of those candles being lit, M'mere speaking the names of Artis and Sergeant Hayes and Corporal Flynn and each of his mess mates. Her strong prayers opening wings above their heads like protective angels.

The next lines made his heart rise up in his chest.

That was the first page. Louis almost did not turn to the second. But Artis, who was looking over his shoulder, nudged him hard in the back.

“Keep on. I want to know more about all them kids you are going to have.”

Louis turned the page, took a breath and pressed on.

His ears were burning, but Artis nudged him again.

“That's not the end of it,” Artis said. “It's getting good.” Louis read on.

Louis folded the pages back up and slipped them into the envelope. He unbuttoned his breast pocket, tucked the envelope in next to his mother's first letter, buttoned the pocket again.

“Who's Azonis?” Artis asked.

“A girl,” Louis said in a grudging voice.

“Well, I hoped to God she wasn't a chicken,” Artis chuckled. “Seeing as how your ma has you already married off to her and is counting on twelve grandchildren.”

Louis spun toward Artis, his hands balled up into fists. “Don't you dare tell anyone about this!”

Artis stepped back, both hands raised with open palms. “Whoa up, Louis. I won't breathe a word about it to a soul. You really like this girl, eh?”

The picture of Azonis Panadis's sweet young face looking over at him as they sat side by side in the Church of St. Ann filled Louis's memory. Her long black hair had fallen over one of her eyes, dark eyes that twinkled with mischief and intelligence. Their families had known each other forever. Sometimes they had traveled together and the father of Azonis had been one of his own father's closest friends.

Azonis.

They had played together when they were little children. Her ideas had always gotten him into troubleâlike the time she decided they should dress their dogs up like people and one of M'mere's best blouses had ended up getting torn. He had always followed her, done whatever she told him to do. She was a year older than him, had been taller than him. Until this last year when he had grown to be as big as a man and he had noticed that when she looked at him she had to lift up her chin. And she had stopped telling him what to do. Instead she had begun looking at him as if she expected him to say something.

He had thought of her. And now he knew that she had been thinking of him.

She holds me in her memory.

Louis felt as if his feet were about to leave the ground.

“Yes,” he said. “I really do like her.”

By the time Louis got back, it was time to eat. He did so in a happy silence, but despite the fact that Louis's thoughts were on his memories of the face of Azonis Panadis, he still heard the feet quietly approaching him from behind.

Louis turned toward Sergeant Flynn before his name was spoken.

“Sir.”

The burly sergeant shook his head. “There's no sneaking up on you, is there, me boy?”

“No, sir.”

Flynn laughed.

“Good tidings, me boy. There's t' be no more attacking. We'll be falling back from the line.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

ACROSS THE WIDE RIVER

Monday, June 13, 1864No rest for the weary. We must of covered thirty miles since yesterday's sunset

.

.

They might be falling back, but they were not retreating. Although they'd been through some of the worst fighting in the war and were all worn and tired to the bone, they'd been walking through the night. The Irish Brigade was to be part of yet another attempt to get around the defenses between them and Richmond.

The sun in the middle of the sky again, they finally stopped, allowed a few minutes to rest while some obstacle was cleared from the road ahead.

“Lads,” Sergeant Flynn said, “gather here. It's some explanation ye deserve of what we're up t'. Even though we've seen the elephant, there's more ahead for us and it's toe the mark. Petersburg is where me betters say we're bound.”

Flynn picked up a stick and made two lines in the soft ground.

“Now here's us, the Army of the Potomac. And here's dear old General Lee and his boys hunkering down, 'n' expecting another frontal attack.”

Flynn chuckled, though there was not much humor in it, as he drew a long arrow leading back and around.

“But here's us now. One hundred thousand men tippy-toeing away and not a Rebel aware they're facin' empty trenches. Sure and it'll be another day before they discover we've moved to come at Richmond from below and behind.”

Flynn scraped a curving line and jabbed in the point of the stick. “Crossing here.”

“The James River?” Corporal Hayes asked.

From the tone of his voice, he doesn't sound much interested

.

.

“Aye. They're putting in a great pontoon bridge t' bring across the horses and mules and the heavy artillery and the wagons. But the river is wide. It'll take at least a day or two to get that bridge built. And since there's not a Moses among us to part the waters, the Second Corps, all twenty-two thousand strong, including us fine fighters of the Sixty-ninth, will be floatin' over first by ferry boats.”

Is that a river or an ocean?

The broad expanse of water that shone below them looked to be a mile wide. The light of a sun soon to set beyond the far side danced on the top of big waves.

How can anyone throw a bridge across that?

There was feverish activity on the near bank. Engineers were assembling pontoons and stacking great loads of planks on flatboats.

“Two miles down from here,” Flynn said, coming up on Louis's right, “that's where the river narrows to a mere half mile. Ye might find it hard to envision, but for certain sure they're going to span the James.”

Wish I could see that bridge when it's done. It'll be a wonder, for sure.

Gunports and transport barges were being pulled up to the landing below them. The engineers and navy boys on board all stared at the men of the 69th as they marched by.

“What are them popinjays in their pretty blue uniforms googling their eyes at?” Belaney muttered.

“They're just admiring our fine duds,” Kirk said, “and wondering where they might find clothes so well decorated with sweat and mud and dust and blood as ours.”

Louis glanced down at the tattered sleeves of his coat, the holes in the knees of his pants, his boots stained red from Southern mud and dust.

We're a regiment of scarecrows compared to them with their pressed pants and coats and their clean faces. But would they look as good if they'd just been fighting and marching and sleeping in the dirt like us for the last six weeks?

Soon they were on the bobbing deck of the first of the transport ships.

“Been on the water before?” Songbird asked.

“Some,” Louis answered. “But never in a boat the size of a house.”

“Twice as big as any house I ever lived in,” Kirk said, leaning over the rail.

How can something as large as this float? Listen to how them planks thump under our feet. Almost like a drum. Won't this be something to write M'mere and Azonis about?

By dawn of the next day, they were all across and assembled at Windmill Point. But the expected order to move out hadn't come. The sun now stood two hands high above the horizon. Sergeant Flynn, who had gone off to find out what the delay was, was just returning.

“Sergeant, sir,” Kirk said, “have the officers finished having their breakfast yet? Or will we be waiting till they've had dinner?”

Flynn shook his head in disgust. “Our orders now are for the whole of Second Corps t' sit and wait for the arrival of sixty thousand rations from General Butler that we're to carry with us to Petersburg.”

“Hurry up and wait,” Louis said, surprising himself by speaking his thoughts aloud.

The other men chuckled at his words, but Flynn's face stayed grim.

“I'll wager you boys a dollar against a donut,” Sergeant Flynn growled, “that them rations never do get here. But there's no point t' complaining. For it's the joy of me life that when things go wrong in this army, with the fine generals we have leading us, they kin always go worse.”

Flynn's words were a prophecy. By midmorning, when no rations had arrived, a disgusted General Hancock decided they'd waited long enough. They set out on what was supposed to be a sixteen-mile march to Petersburg to join the 16,000 men of General Smith's Corps who had crossed the Appomattox River to the west and would reach Petersburg first.

Other books

Dragons Rising by Daniel Arenson

Blackmailed by the Italian Billionaire by Nina Croft

ARC: Under Nameless Stars by Christian Schoon

Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter by Nina MacLaughlin

People Who Knock on the Door by Patricia Highsmith

The Azure Wizard by Nicholas Trandahl

Feeding the Hungry Ghost by Ellen Kanner

Board Approved by Jessica Jayne

Salby Damned by Ian D. Moore

El águila de plata by Ben Kane