March Toward the Thunder (17 page)

Read March Toward the Thunder Online

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

I'll hear those cries in my dreams. And then, even worse, I'll hear that silence.

On the fourth day, the seventh of June, an agreement was reached. Parties of stretcher bearers dashed into the field from North and South alike. Hundreds had been crying for aid just after the battle, but only two were found still living. Scant work for the doctors, but more than enough for those like Louis who volunteered to dig graves.

Louis turned from the vantage point over the deadly ground between the armies.

And now, to top it all off, our leaders are fighting each other.

Joker had passed on the latest gossip to him just that morning. Their own Union generals were now at bitter odds with each other.

It wasn't Grant's meat-grinder approach, using up men like cattle sent to the slaughter, that had stirred up opposition from the other top generals. Bloody Grant was getting more praise in the press than the rest of them. Getting good publicity meant almost as much as winning battles.

As Louis passed men who knew him, some raised a hand in tired greeting, but none said a howdy-do.

Too worn out to even talk.

Not just from the work, but from the blasted heat and the constant uncertainty.

No one ever knows what to expect next. And thinking of that, what the Sam Hill is happening now?

Ahead, men were standing up and pointing.

“Oh my Lord!” someone shouted from down the length of the trench, standing up and waving to Louis. It was Joker. Songbird and Bull were by his side. “Come see the circus what's come into town.”

Louis quickened his pace to join them.

What's that heading our way? Oh my Lord, indeed!

A man seated backward on a mule was being led their way. A large placard was fastened to his chest. A drummer walking in front beat out the “Rogue's March” as the unfortunate rider was paraded through camp. Men were hooting and hollering. Some tossed clods of mud as the unfortunate man passed them.

“What's them signs say?” Bull asked. “I ain't got me spectacles.”

Louis read the sign aloud.

“Libeler of the press.”

“And what might that mean?” Songbird mused.

The officer holding the reins of the mule lifted his hand. The crowd quieted as he brandished a piece of paper.

“General Meade's proclamation. It reads, âThis reporter, one Edward Crapsey, the

Philadelphia Inquirer

correspondent, is to be put without the lines of this camp and not allowed to return for repeating base and wicked lies to the effect that only General Grant wanted to keep moving south and that General Meade was on the point of committing a blunder unwittingly.'”

Philadelphia Inquirer

correspondent, is to be put without the lines of this camp and not allowed to return for repeating base and wicked lies to the effect that only General Grant wanted to keep moving south and that General Meade was on the point of committing a blunder unwittingly.'”

The officer lowered his hand, the drummer began to beat out the march again, and the little procession continued on.

“Now there's the reason why General Meade will never be the president of this land,” Kirk said.

“How's that?” Louis said.

Kirk pointed a finger toward the sky. “While we're fighting it out on these lines, Chief, our generals up there are already looking to what they'll do when the war is over. Every bit of fine publicity Grant gets puts him closer to that highest office. Being the winning general at Gettysburg, for a time the Old Snapping Turtle was the man of the hour. Now his star is falling while Bloody Grant's goes ever higher.”

How, in the middle of a war, could a general think about becoming president?

Louis shook his own head to try to clear it.

“Now Meade's a gone goose for sure,” Kirk continued, dropping his hand.

“How's that?” Devlin asked.

Kirk grinned. “Songbird, if your family was involved in politics like mine is back home in Albany, you'd understand that there's one enemy no one can ever defeat, even a major general who's been a hero of the republic. That enemy's not Robert E. Lee, but one a good deal nastier. The press. Mark my words, from this day on you'll never again read a good word about the old Snapping Turtle in any paper.”

The procession was a good fifty yards away and had stopped once more for the proclamation to be read. Even at that distance, Louis could see the look on the mud-spattered reporter's face was more angry than humiliated.

“War is bloody,” Kirk concluded, “but politics and reporters is worse.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

THE INDIAN GENERAL

Thursday, June 9, 1864What day is this? The ninth? Maybe the tenth?

When they weren't fighting, a day could drag on as if it were a week. Then there'd be a battle and nights and days would streak past fast as falling stars across the sky.

One thing for sure, it was near time to eat. Louis's stomach was telling him that. Back down the trench the cooking fire was goingâfed by the rails they'd pulled from a fence back a hundred yards behind the fortifications. But first he was going to take his letter to the mail wagon.

One of the men by that cooking fire cleared his throat and started to sing. Songbird, of course. As always, the tune he chose was one that fit what they all felt.

“Just before the battle, Mother,

I am thinking most of you.

While upon the field we're watching,

with the enemy in view.

Comrades brave are round me lying,

filled with thoughts of home and God;

For well they know that on the morrow,

some will sleep beneath the sod.”

I am thinking most of you.

While upon the field we're watching,

with the enemy in view.

Comrades brave are round me lying,

filled with thoughts of home and God;

For well they know that on the morrow,

some will sleep beneath the sod.”

Mother

.

.

He patted the breast pocket that held the letter from M'mere. The letter in his hand was his most recent letter to her. As in all the others he'd written, there was little about fighting and much about his friends, the food they ate, the land they marched through, the interesting people he metâlike Artis Cook, who was walking along with him to send out a letter of his own

“Am I in that?” Artis pointed with his chin at the sealed letter in Louis's hand as they strolled toward the mail wagon. “You tell her about my trying to turn you into a civilized Indian like us Iroquois.”

“As I recall, I told my mother that she was right about Mohawks being the ugliest Indians on the continent.”

“Second-ugliest.”

The two walked on a ways in silence.

“Bet you told her about us meeting the general,” Artis said, his voice serious for a change.

Louis nodded. “He really is something special!”

“Wasn't it grand when he called the two of us over to him?” Artis said. His face was glowing now.

The two of them had been playing marbles againâLouis down by a dozenâwhen word reached them that none other than the Big Indian himself was inspecting their fortifications.

The Big Indian. That was what everyone called Brevet General Ely S. Parker, the broad-shouldered Seneca soldier who was the highest-ranking Indian in the whole Union army. He was a field engineer and reputed to be one of the best-educated men in the army. He was also Grant's close friend and personal secretary. And in addition to that, he was one Indian who truly could be called a chief. He'd been chosen by his Seneca people to be their Grand Sachem.

The marbles game was abandoned. The two of them headed to the easternmost fortifications where the general was rumored to be.

“From what I hear,” Artis said as they made their way around a redoubt, “General Parker saved Grant and his staff from falling into an ambush back in the Wilderness. Grant was trying to check on the front but got lost in that tangle of roads and fallen trees. Parker was the only one who realized where they were. He turned their party around just as a Rebel company was about to close in and cut them off.”

Artis was so busy telling his story that they almost stumbled down the embankment into the backs of a party of officers gathered on the lower side of the redoubt. None of them paid any notice to the two boys. They were listening too intently to the broad-shouldered officer with jet-black hair, neatly trimmed goatee and mustache who sat high on horseback before them.

“Another eighteen inches of soil should be added to those traverses,” the brown-skinned man was saying, “if your intent is to defilade the interior space of your field works.”

The Big Indian, for sure. No other high-ranking officer has a face like that. He surely does look like a chief too

.

.

Finally, the engineers began to drift away now from the big man, their conference finished. General Parker sat there, as if lost in his thoughts.

“Think he feels as far away from home as we do?” Louis whispered to Artis.

General Parker turned his head slightly in their direction.

Eyes like a hawk's.

The shadow of a smile came to the Indian general's face. “Soldiers,” he said, lifting one hand from the reins, “come on over here.”

They were down the embankment in a flash.

“Yes, sir!” they said as one, snapping a salute to the mounted man.

And won't this be something to write home to M'mere about? An Indian general on a fine black horse passing the time of day with me?

The general looked down at them, the subtle smile still on his face. Then he cleared his throat and focused his hawk eyes on Artis.

“Skanoh,”

General Parker said.

General Parker said.

“Sehkon,”

Artis answered.

Artis answered.

The general laughed out loud. “Hah! So you're a Mohawk, eh?”

“Yessir, been that way all my life.” Artis grinned.

It wasn't the kind of remark Louis imagined most soldiers making to a superior officer, fellow Iroquois or not, but it seemed to tickle General Parker, as his smile broadened.

He turned slightly in his saddle to look down at Louis. The general's horse took a step closer to Louis and began nuzzling his shoulder the way most horses did whenever Louis was near. Louis stroked its nose.

The general chuckled and leaned forward to pat his horse's neck. “Found a new friend, have you, Midnight?” he said softly.

Then his voice deepened again. “Good with horses, are you?”

Louis wondered if he'd overstepped by being so familiar with the general's horse. He felt his ears redden.

“I . . . I suppose so, sir,” he stammered, looking down.

“At ease, son.” Out of the corner of his eye Louis saw the imposing man above him was studying his face. “Not Haudenosaunee, though. Not one of our longhouse people?”

“No sir, Abenaki.”

“Ah, a people of great determination.”

Those words, spoken with such warmth and certainty, removed any embarrassment Louis had been feeling. They needed no reply and so he didn't make one. He stood there, Artis by his left side, the general looking off in the distance, the three of them enjoying a companionable silence.

General Parker cleared his throat again.

“How old are you two boys?”

Artis answered first.

“Just gone eighteen,” he said.

It never occurred to Louis to do anything but tell the plain truth. Plus that piece of paper in his shoe had worn out long ago.

“Fifteen, sir.”

The look on General Parker's face changed a little then. It had been friendly before, but now there was something like tenderness in the way the dark-mustached man looked down and nodded.

“I thought as much. And I'll bet there's not a white man in this army who thought you less than seventeen.”

“Suppose not,” Louis said, looking up with a grin. General Parker lifted his right hand to tap the place where the brown skin of his own left wrist was exposed above the riding glove.

“It takes another Indian to know, doesn't it?”

“Yessir,” Louis said, turning his eyes politely back down toward the ground.

Neither of them uttered a word beyond that, but to Louis that long moment of silence they shared was when they said the most to each other. It was not like with some white men who get nervous when you don't chatter like a jaybird.

General Parker took off his glove. He touched his right hand to his heart, then held that hand out to Louis, who took it in an Indian handshake. Their strong right hands together in a loose, relaxed way as strong as the flow of water. The general leaned farther over to shake with Artis.

“Niaweh,”

Artis said.

Artis said.

The Indian general shook his head. “No, my boy. It is I who should thank you and your friend for your service.

Niaweh hah!

”

Niaweh hah!

”

General Parker straightened, nodded one final time, and rode away.

A good thing to write to his mother about. In fact, it took up most of the two pages of paper that Louis had been able to scrounge. Paper was sometimes scarce as hen's teeth. Everyone who could manage to scribble a few words was writing home whenever they had a spare moment.

Must be ten tons of letters traveling between Virginia and the North every week.

And some back in the other direction too.

“Nolette, Louis,” the man on the wagon called out. It surprised Louis so much that he couldn't answer.

“Here!” Artis shouted for him, before the mail clerk could put the letter away.

If it hadn't been for Artis, he might not even have gotten that letter. So Louis started reading the letter aloud to him as soon as he opened it. Once he'd started, though, it was too late to stop when it got embarrassing.

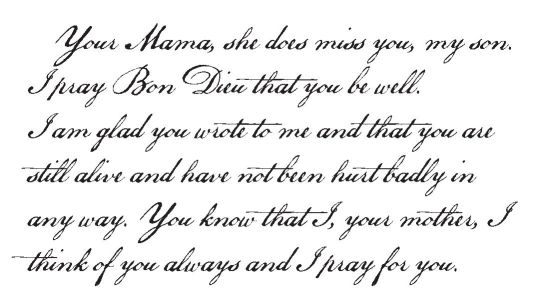

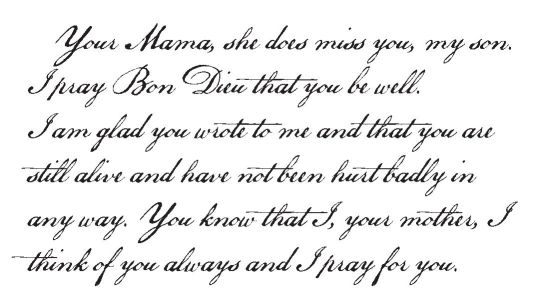

The handwriting was the same as before but this letter was more than twice as long. It began as it had before:

Other books

Adrenaline by Jeff Abbott

The Iron Palace by Morgan Howell

Gold Boy, Emerald Girl by Yiyun Li

Black Seconds by Karin Fossum

Home Invasion by William W. Johnstone

The Perfect Outsider by Loreth Anne White

Haunted Castles by Ray Russell

Famished by Hammond, Lauren

Lost in Magic (Night Shadows Book 4) by Wulf,Rose

One Wild Night by Jessie Evans