Mark Griffin (16 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Brecher and collaborator Fred Finklehoffe

y

started from scratch, restoring the whimsical, homespun qualities of Benson’s original narrative. This version of the

St. Louis

screenplay fleshed out episodes that Benson had only alluded to—a sisterly cakewalk, a ride on the trolley, and a Christmas Eve cotillion. By July 1943, Brecher had turned in a completed script, and although it looked promising, there was unified resistance to

Meet Me in St. Louis

by MGM’s upper echelon.

y

started from scratch, restoring the whimsical, homespun qualities of Benson’s original narrative. This version of the

St. Louis

screenplay fleshed out episodes that Benson had only alluded to—a sisterly cakewalk, a ride on the trolley, and a Christmas Eve cotillion. By July 1943, Brecher had turned in a completed script, and although it looked promising, there was unified resistance to

Meet Me in St. Louis

by MGM’s upper echelon.

“The studio did not want to make

Meet Me in St. Louis

,” Brecher recalled:

Meet Me in St. Louis

,” Brecher recalled:

The reason it was made and we were rushed into doing a script was because at that time in Hollywood, there were only two existing Technicolor cameras and they were always in demand because color meant a lot at the box office. All of a sudden, one of the cameras became available and MGM had a contract, which it had to exercise within a brief period of time, to use it. In desperation, Freed and his bosses got the idea with this story, “If it has Judy Garland and color, maybe we’ll make a few bucks.” When it got close to where they were going with casting and all of that, I talked to Freed and we were discussing directors and I said I didn’t think anybody could do it better than Minnelli.

2

2

Brecher had never worked with Minnelli, but he certainly knew of his reputation—and not only as a director:

I met Minnelli when he was shooting

Cabin in the Sky

. I sensed even in those days that he was maybe a queer. I wasn’t sure. But he didn’t come on to me

and he didn’t swish. But there was something about the way Minnelli would open a cigarette box and take one out and light it . . . very effete. It was almost like a caricature of a gay guy. And there was something about the way he used his hands and twisted his lips and wore green eye shade and hung with all the gays, like Don Loper, the dance director, who was out and I mean

out

. Vincente was part of the Freed Unit, which was the gay community there. Freed wasn’t gay but the rest of them were. . . . At any rate, Freed liked the idea of reaching for Vincente as the director of

St. Louis

. And without question, Minnelli was perfect for that picture.

3

Cabin in the Sky

. I sensed even in those days that he was maybe a queer. I wasn’t sure. But he didn’t come on to me

and he didn’t swish. But there was something about the way Minnelli would open a cigarette box and take one out and light it . . . very effete. It was almost like a caricature of a gay guy. And there was something about the way he used his hands and twisted his lips and wore green eye shade and hung with all the gays, like Don Loper, the dance director, who was out and I mean

out

. Vincente was part of the Freed Unit, which was the gay community there. Freed wasn’t gay but the rest of them were. . . . At any rate, Freed liked the idea of reaching for Vincente as the director of

St. Louis

. And without question, Minnelli was perfect for that picture.

3

Even before shooting a single frame, Vincente was under pressure. If all went according to plan, he’d be entrusted with MGM’s most valuable asset, a twenty-one-year-old supernova named Judy Garland. If the picture was a hit, it could make his career. There was just one problem. Garland didn’t want to make

Meet Me in St. Louis

. The star had finally graduated to more mature roles in

For Me and My Gal

and

Presenting Lily Mars

. The idea that she should regress and play yet another wholesome teenager—and opposite a couple of scene-stealing child stars to boot—didn’t exactly thrill her.

Meet Me in St. Louis

. The star had finally graduated to more mature roles in

For Me and My Gal

and

Presenting Lily Mars

. The idea that she should regress and play yet another wholesome teenager—and opposite a couple of scene-stealing child stars to boot—didn’t exactly thrill her.

Several key players associated with production #1317 would take credit for cajoling Garland into boarding that St. Louis trolley, including Irving Brecher, who recalled reading the entire script to Judy at the urging of studio chief Louis B. Mayer. “I had a hell of a time with her,” Brecher recalled:

I had to make her believe that her scenes were the most important in the picture. So, when I was reading to her, I threw away the kid sister’s stuff because Judy was afraid Tootie would steal the picture. . . . Like anyone could steal a picture from Garland. Judy had been to my home a number of times at parties and she liked me and kind of trusted me but she was very ambivalent and troubled about

St. Louis

. I finally broke her down and she weakly said, “Do you really think I’ll be alright?” I said, “It’s your picture, Judy. It’ll be the best thing you ever did.” And I hoped I was telling the truth.

4

St. Louis

. I finally broke her down and she weakly said, “Do you really think I’ll be alright?” I said, “It’s your picture, Judy. It’ll be the best thing you ever did.” And I hoped I was telling the truth.

4

In Minnelli’s 1974 memoir, it is Garland’s director who attempts to convince her of the project’s special merits. “I wasn’t aware of her feelings when I first discussed the role with her,” Vincente remembered. “She looked at me as if we were planning an armed robbery against the American public.”

“It’s not very good, is it?” Judy challenged Vincente, expecting that Minnelli, the urbane New York sophisticate, would dismiss

St. Louis

as nothing more than sentimental, candy-colored tripe.

St. Louis

as nothing more than sentimental, candy-colored tripe.

“I think it’s fine,” Vincente answered. “I see a lot of great things in it. In fact, it’s magical.”

5

5

With Garland more or less persuaded, the other essential bit of casting concerned Tootie, the mischievous five-year-old member of the Smith household, partially patterned on Sally Benson herself. The role required an unusually adept child performer who could convincingly play precocious, execute a sprightly cakewalk, and become tearfully inconsolable on cue. From the moment casting ideas were floated, Margaret O’Brien was the only serious contender. Minnelli would claim credit for “discovering” O’Brien after witnessing her audition for

Babes on Broadway

, the musical in which she would make her debut. O’Brien’s dynamic audition included her impassioned plea, “Don’t send my brother to the chair! Please don’t let him fry!”

Babes on Broadway

, the musical in which she would make her debut. O’Brien’s dynamic audition included her impassioned plea, “Don’t send my brother to the chair! Please don’t let him fry!”

Production began on December 7, 1943. “It’s strange but I can remember everything that happened on that set,” Margaret O’Brien says. “It was a very quiet set because Vincente Minnelli kept everything quiet and lovely for the actors.”

6

Through the eyes of a talented six-year-old everything may have seemed quiet and lovely, but the studio’s production reports tell a different story. Injuries and illnesses were almost a daily occurrence. Joan Carroll required an emergency appendectomy. Mary Astor suffered from an acute sinus condition. Margaret O’Brien battled hay fever, influenza, and nervous spells. A month into production, Margaret’s mother, Gladys, wrote to Freed and explained that she was pulling her daughter out of the picture for a few weeks. As she put it, “I was beginning to be greatly criticized for allowing my child to work so hard.”

7

6

Through the eyes of a talented six-year-old everything may have seemed quiet and lovely, but the studio’s production reports tell a different story. Injuries and illnesses were almost a daily occurrence. Joan Carroll required an emergency appendectomy. Mary Astor suffered from an acute sinus condition. Margaret O’Brien battled hay fever, influenza, and nervous spells. A month into production, Margaret’s mother, Gladys, wrote to Freed and explained that she was pulling her daughter out of the picture for a few weeks. As she put it, “I was beginning to be greatly criticized for allowing my child to work so hard.”

7

And then there was Judy.

Minnelli’s skittish leading lady was still unable to completely relate to the story. Once before the cameras, Garland mocked what she perceived to be the trite, juvenile aspects of the script. On the first day of principal photography, newcomer Lucille Bremer (cast as the oldest Smith sister, Rose) was imbuing her performance with the kind of wholehearted sincerity that Garland ordinarily invested in her roles, no matter how banal. “I want you to read your lines as if you mean every word,” Minnelli told Garland. Known as the quickest quick study in the business, Judy complied, but she seemed thrown by Minnelli’s unconventional approach. Discouraged, Judy confided in Arthur Freed that Vincente’s cryptic direction wasn’t providing her with the guidance she needed. “She says she doesn’t know what you want,” Freed repeated back to Minnelli. “She doesn’t feel she can act anymore.”

8

8

When Garland griped to veteran actress Mary Astor about Vincente’s mystifying direction, the colleague Judy referred to as “Mom” offered a sharp

dose of motherly advice. “Judy, I’ve been watching that man and he really knows what he’s doing,” Astor responded. “Just go along with it, because it means something.”

9

dose of motherly advice. “Judy, I’ve been watching that man and he really knows what he’s doing,” Astor responded. “Just go along with it, because it means something.”

9

Although Garland attempted to go along with Minnelli, she didn’t surrender completely. When Vincente summoned the cast for yet another rehearsal, Judy defiantly sped off in her roadster. Minnelli had his star intercepted at the studio gate and brought back to work. Getting Judy to the set and keeping her there would become a regular concern for a number of production assistants on the MGM payroll.

“Well, of course, Judy was always late,” recalls June Lockhart, who costarred in the film as Eastern debutante Lucille Ballard:

It was rather interesting because we would come into make-up at six-thirty and then get

under

-dressed because in that film, we even wore the underwear of the period. Then they’d give us a robe and we’d wait because Judy hadn’t arrived yet and then we’d wait some more and finally, at about twelve-thirty, they’d say, “Well, Judy’s come through the gate. You can all go to lunch. Come back around two.” So, we’d come back at two and then they would say, “Well, she doesn’t want to work today. So, you can all go home.” And this happened a lot. But let me tell you, when she came on the set all dressed and ready, she knew her lines and where her marks were and she was funny and entertaining to be with and I think by then, was thoroughly enjoying playing the part.

10

under

-dressed because in that film, we even wore the underwear of the period. Then they’d give us a robe and we’d wait because Judy hadn’t arrived yet and then we’d wait some more and finally, at about twelve-thirty, they’d say, “Well, Judy’s come through the gate. You can all go to lunch. Come back around two.” So, we’d come back at two and then they would say, “Well, she doesn’t want to work today. So, you can all go home.” And this happened a lot. But let me tell you, when she came on the set all dressed and ready, she knew her lines and where her marks were and she was funny and entertaining to be with and I think by then, was thoroughly enjoying playing the part.

10

It also didn’t hurt that for

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Garland would have the privilege of introducing three original songs: “The Boy Next Door,” “The Trolley Song,” and “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”—each one a masterpiece. The trio of songs would advance the plot as effectively as the dialogue or action. “I had read the script and I knew there was a Christmas scene,” recalls composer Hugh Martin, who wrote the songs with partner Ralph Blane. “I was doodling on the piano while Ralph was working on lyrics. I worked on this tune for a couple of days and couldn’t make it go anywhere. It just sort of lay there after the sixteenth bar. About the third day, Ralph said, ‘I know I’m not supposed to be listening, but you were playing a very pretty little madrigal type tune for a couple of days and then I didn’t hear it anymore. It really bothered me because I think you had something good there.’”

11

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Garland would have the privilege of introducing three original songs: “The Boy Next Door,” “The Trolley Song,” and “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”—each one a masterpiece. The trio of songs would advance the plot as effectively as the dialogue or action. “I had read the script and I knew there was a Christmas scene,” recalls composer Hugh Martin, who wrote the songs with partner Ralph Blane. “I was doodling on the piano while Ralph was working on lyrics. I worked on this tune for a couple of days and couldn’t make it go anywhere. It just sort of lay there after the sixteenth bar. About the third day, Ralph said, ‘I know I’m not supposed to be listening, but you were playing a very pretty little madrigal type tune for a couple of days and then I didn’t hear it anymore. It really bothered me because I think you had something good there.’”

11

Something good indeed. Although “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” would become a holiday institution as indispensable as eggnog, the original lyrics posed a problem, as they included such downbeat lines as “Have yourself a merry little Christmas. . . . It may be your last.” As Martin remembers, Garland liked the song but not the suicidal lyrics: “Judy quite

wisely said, ‘If I sing that song to little Margaret O’Brien, the audience will hate me. They’ll think I’m a monster.’ So, they came to me and said, ‘Judy loves the melody and she wants you to write a new lyric, please.’ Being stupid, I said I wouldn’t and I stuck to my guns.” It was the boy next door to the rescue. “Tom Drake came to me and said, ‘You’re being an absolute horse’s ass and I’m not proud of you and if you miss this opportunity to have a great, classic Christmas song, I will never speak to you again.’ And I thought, well, he’s a sensible man and he’s not too dumb and I went home that night and I wrote the lyric that was in the movie.”

12

wisely said, ‘If I sing that song to little Margaret O’Brien, the audience will hate me. They’ll think I’m a monster.’ So, they came to me and said, ‘Judy loves the melody and she wants you to write a new lyric, please.’ Being stupid, I said I wouldn’t and I stuck to my guns.” It was the boy next door to the rescue. “Tom Drake came to me and said, ‘You’re being an absolute horse’s ass and I’m not proud of you and if you miss this opportunity to have a great, classic Christmas song, I will never speak to you again.’ And I thought, well, he’s a sensible man and he’s not too dumb and I went home that night and I wrote the lyric that was in the movie.”

12

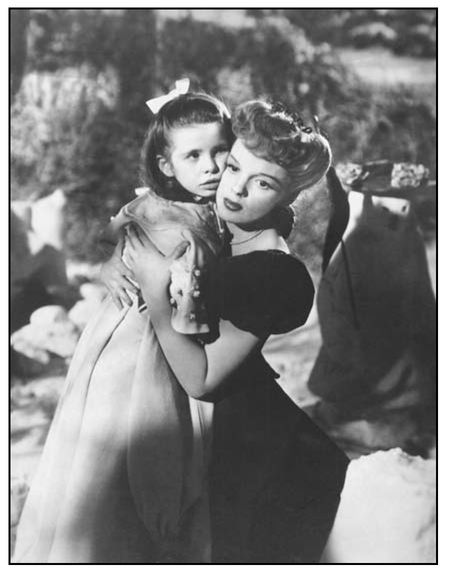

Margaret O’Brien and Judy Garland in

Meet Me in St. Louis

. “Vincente Minnelli kept everything quiet and lovely for the actors,” O’Brien says. “He was certainly in charge but in a very charming, gentle, and understanding way.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Meet Me in St. Louis

. “Vincente Minnelli kept everything quiet and lovely for the actors,” O’Brien says. “He was certainly in charge but in a very charming, gentle, and understanding way.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Lovingly photographed by George Folsey,

z

Garland would never look better on film than she did in

St. Louis

. Apart from a standout vignette in

Thousands Cheer

, released the year before,

St. Louis

would be the first feature since

The Wizard of Oz

that allowed Judy’s legions of followers to view their Metro goddess all aglow in vibrant Technicolor. Despite the fact that Garland had been reluctant to take on another dewy ingenue, there is an appealing

freshness and genuine warmth to her Esther Smith. Freed from Andy Hardy, Busby Berkeley, and her outmoded ugly duckling image, a new Judy Garland emerges in

Meet Me in St. Louis

, and she’s a real beauty.

z

Garland would never look better on film than she did in

St. Louis

. Apart from a standout vignette in

Thousands Cheer

, released the year before,

St. Louis

would be the first feature since

The Wizard of Oz

that allowed Judy’s legions of followers to view their Metro goddess all aglow in vibrant Technicolor. Despite the fact that Garland had been reluctant to take on another dewy ingenue, there is an appealing

freshness and genuine warmth to her Esther Smith. Freed from Andy Hardy, Busby Berkeley, and her outmoded ugly duckling image, a new Judy Garland emerges in

Meet Me in St. Louis

, and she’s a real beauty.

Make-up artist Dorothy “Dottie” Ponedel refined Judy’s look for the film, giving her a fuller lower lip and introducing what was to become Garland’s trademark arched eyebrow. More important than any cosmetic enhancements was that Garland also found a close friend and trusted confidante in Ponedel. “It was amazing to watch the two of them together,” Meredith Ponedel says of her Aunt Dottie’s legendary rapport with Judy. “Vincente respected the fact that Judy would respond to Dot when she wouldn’t respond to anybody else.”

13

However, midway through production on

St. Louis

, Garland suddenly became very responsive to Minnelli. And was it possible that Vincente was becoming interested in Judy for reasons that had nothing to do with how she recited her lines? Exactly what was Minnelli seeing as he gazed through his viewfinder at the twenty-one-year-old Garland?

13

However, midway through production on

St. Louis

, Garland suddenly became very responsive to Minnelli. And was it possible that Vincente was becoming interested in Judy for reasons that had nothing to do with how she recited her lines? Exactly what was Minnelli seeing as he gazed through his viewfinder at the twenty-one-year-old Garland?

Just like her director, Judy had been born into show business. Frances Gumm (as Garland was originally named) had been performing since the age of two, appearing with her two sisters in lesser vaudeville houses across the country. Her incomparable voice, sincere delivery, and unique personality had landed her an MGM contract in 1935. Almost from the moment Judy Garland had arrived at MGM, the studio’s star-making magicians had been determined to have her problematic figure match her remarkable voice. Chocolate cake was confiscated, and Benzedrine prescribed. There were the unflattering comparisons to studio sirens Lana Turner and Elizabeth Taylor. As a young woman, Judy was made to understand that her extraordinary talents would have to be continuously switched on to compensate for a basic unworthiness.

Other books

Mycroft Holmes by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Lost Among the Angels (A Mercy Allcutt Book) by Duncan, Alice

Full Count by Williams, C.A.

Ever After by Jude Deveraux

Raisonne Curse by Rinda Elliott

Cleopatra Confesses by Carolyn Meyer

Los griegos by Isaac Asimov

Concealed in Death by J. D. Robb

Accidental SEAL (SEAL Brotherhood #1) by Hamilton, Sharon

Metal Boxes - Rusty Hinges by Alan Black