Mark Griffin (35 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Even at a significantly reduced running time of 124 minutes,

The Cobweb

still seems ponderously paced, a fact that was not lost on the critics: “A select minority among filmgoers may find the even-keeled clinical study interesting, but there’s not enough contrast between its dramatic highs and lows, nor sufficiently developed sympathy for the characters to attract the entertainment fancy of the majority,”

Variety

decided.

Film Daily

noted, “The picture is on the cerebral side, lacking the impact and mood which would have made for more emotional appeal.” The most memorable review belonged to Philip T. Hartung, who famously dubbed the picture “The Drapes of Wrath.”

The Cobweb

still seems ponderously paced, a fact that was not lost on the critics: “A select minority among filmgoers may find the even-keeled clinical study interesting, but there’s not enough contrast between its dramatic highs and lows, nor sufficiently developed sympathy for the characters to attract the entertainment fancy of the majority,”

Variety

decided.

Film Daily

noted, “The picture is on the cerebral side, lacking the impact and mood which would have made for more emotional appeal.” The most memorable review belonged to Philip T. Hartung, who famously dubbed the picture “The Drapes of Wrath.”

And as for the author, William Gibson says, “I found it totally boring.” And what’s more, he was finished with Hollywood. “I thought . . . this is not where I want to spend my life. It’s a choice between their money and my words and I think I’ll go home and live with my words.” Gibson was so turned off by his experiment in movie-making that even when Minnelli and Houseman dangled a plum assignment before him, he could not be moved. “On my last day, they offered me the chance to write their next movie. I said, ‘No, I’m going back to Stockbridge to work on a play of my own. They kept talking about this movie they were going to make about van Gogh,

Lust for Life

. Minnelli said to me, ‘I think it can be a masterpiece.’”

17

Lust for Life

. Minnelli said to me, ‘I think it can be a masterpiece.’”

17

21

Stranger in Paradise

IF MINNELLI COULDN’T WAIT to get to

Lust for Life

and explore the tormented psyche of Vincent van Gogh, he couldn’t have been less interested or more uninspired by

Kismet

, which was standing in his way. Although Vincente had turned down Arthur Freed’s invitation to direct a lavish screen version of the Broadway show, Dore Schary simply wouldn’t take no for an answer. “We need you desperately for

Kismet

,” Schary implored. “You could direct it before you go to Europe for

Lust for Life

.”

1

Although the studio chief reached out to Vincente in the form of an impassioned plea, there was an implicit ultimatum behind Schary’s words—if Minnelli didn’t direct

Kismet

, there would be no

Lust for Life

.

Lust for Life

and explore the tormented psyche of Vincent van Gogh, he couldn’t have been less interested or more uninspired by

Kismet

, which was standing in his way. Although Vincente had turned down Arthur Freed’s invitation to direct a lavish screen version of the Broadway show, Dore Schary simply wouldn’t take no for an answer. “We need you desperately for

Kismet

,” Schary implored. “You could direct it before you go to Europe for

Lust for Life

.”

1

Although the studio chief reached out to Vincente in the form of an impassioned plea, there was an implicit ultimatum behind Schary’s words—if Minnelli didn’t direct

Kismet

, there would be no

Lust for Life

.

At the height of a 1953 newspaper strike that deprived several Broadway shows of some well-deserved accolades,

Kismet

got lucky. Thanks to good word-of-mouth, audiences flocked to this “musical Arabian night.” With its Robert Wright-George Forrest score adapted from Alexander Borodin’s music, the show produced two hit songs that would become piano bar staples, “Stranger in Paradise” and “Baubles, Bangles and Beads.” Alfred Drake was roundly applauded for his bravura turn as Hajj, the street poet—though even as the actor was taking his curtain calls, theatergoers were already wondering who would end up playing Drake’s part when Hollywood mounted its own version of the show.

Kismet

got lucky. Thanks to good word-of-mouth, audiences flocked to this “musical Arabian night.” With its Robert Wright-George Forrest score adapted from Alexander Borodin’s music, the show produced two hit songs that would become piano bar staples, “Stranger in Paradise” and “Baubles, Bangles and Beads.” Alfred Drake was roundly applauded for his bravura turn as Hajj, the street poet—though even as the actor was taking his curtain calls, theatergoers were already wondering who would end up playing Drake’s part when Hollywood mounted its own version of the show.

Of course, Broadway’s

Kismet

was only the latest interpretation of the shop-worn tale of a poetic beggar who ascends the social ranks to become Emir of Baghdad. Edward Knoblock’s operetta had debuted in 1911. And

by the time Minnelli found himself saddled with it, there had already been three film versions of

Kismet

. The most memorable incarnation had arrived in 1944 and featured Ronald Colman in the lead. This exercise in exotica was best remembered for the indelible spectacle of Marlene Dietrich writhing seductively in a “dance” sequence, her legendary legs coated in gold body paint.

Kismet

was only the latest interpretation of the shop-worn tale of a poetic beggar who ascends the social ranks to become Emir of Baghdad. Edward Knoblock’s operetta had debuted in 1911. And

by the time Minnelli found himself saddled with it, there had already been three film versions of

Kismet

. The most memorable incarnation had arrived in 1944 and featured Ronald Colman in the lead. This exercise in exotica was best remembered for the indelible spectacle of Marlene Dietrich writhing seductively in a “dance” sequence, her legendary legs coated in gold body paint.

On May 23, 1955, production began on Minnelli’s

Kismet

. Stars Howard Keel, Ann Blyth, and Dolores Gray were initially enthusiastic about bringing the Broadway smash to the screen, though, from the outset, their director exhibited impatience with nearly everything concerning the production. It was readily apparent to both cast and crew that of all the films Vincente had helmed so far,

Kismet

was the one project that failed to engage him on any level. “

Kismet

was doomed from the start. Nothing planned fell into place,” an embittered Howard Keel remembered.

2

Kismet

. Stars Howard Keel, Ann Blyth, and Dolores Gray were initially enthusiastic about bringing the Broadway smash to the screen, though, from the outset, their director exhibited impatience with nearly everything concerning the production. It was readily apparent to both cast and crew that of all the films Vincente had helmed so far,

Kismet

was the one project that failed to engage him on any level. “

Kismet

was doomed from the start. Nothing planned fell into place,” an embittered Howard Keel remembered.

2

Minnelli gritted his teeth and soldiered on, but he proceeded with greater haste than ever before. The quiet, infinitely patient auteur of

Meet Me in St. Louis

was suddenly replaced with a tyrannical, Otto Premingerish alter ego. Vic Damone, fresh from warbling Sigmund Romberg in Stanley Donen’s bloated biopic

Deep in My Heart

, had to contend with an openly hostile Minnelli. As Keel remembered it, “Vincente was terrible to Vic. Instead of trying to help him, Minnelli berated him at every opportunity and in front of everyone.”

3

Meet Me in St. Louis

was suddenly replaced with a tyrannical, Otto Premingerish alter ego. Vic Damone, fresh from warbling Sigmund Romberg in Stanley Donen’s bloated biopic

Deep in My Heart

, had to contend with an openly hostile Minnelli. As Keel remembered it, “Vincente was terrible to Vic. Instead of trying to help him, Minnelli berated him at every opportunity and in front of everyone.”

3

And Minnelli wasn’t the only one throwing tantrums. “I was on the set of

Kismet

and I witnessed a nasty scene that Dolores Gray made,” recalled artist Don Bachardy, nineteen at the time and an unpaid assistant to Tony Duquette, who designed the costumes. “Arthur Freed was forcing her to be photographed by daylight. Seeing her in daylight, I couldn’t help but understand her objections. She had a bad complexion and daylight is just murder for that. Especially with make-up over her face . . . and a bad nose job besides.”

4

Gray’s sizzling renditions of “Not Since Nineveh” and “Rahadlakum” more than made up for the actress’s display of temperament, and her scintillating delivery manages to liven things up on screen.

Kismet

and I witnessed a nasty scene that Dolores Gray made,” recalled artist Don Bachardy, nineteen at the time and an unpaid assistant to Tony Duquette, who designed the costumes. “Arthur Freed was forcing her to be photographed by daylight. Seeing her in daylight, I couldn’t help but understand her objections. She had a bad complexion and daylight is just murder for that. Especially with make-up over her face . . . and a bad nose job besides.”

4

Gray’s sizzling renditions of “Not Since Nineveh” and “Rahadlakum” more than made up for the actress’s display of temperament, and her scintillating delivery manages to liven things up on screen.

When Gray is not around, there is always the decor—plus Tony Duquette’s outré Arabian apparel. As Don Bachardy remembered it, Minnelli and Duquette strove to improve upon the work of their predecessors: “I think they were in total agreement about the art work on the previous MGM version of

Kismet

with Dietrich. I think they both agreed that the art work in it was pretty awful.” Determined to outdo Cedric Gibbon’s uninspired settings, Minnelli decided on a monochromatic Mesopotamia but also one that was “like Olsen and Johnson in Baghdad . . . very beautiful and chic.”

5

Duquette

let his imagination run wild, conjuring up enough colorful Arabian finery to satisfy a thousand and one nights.

Kismet

with Dietrich. I think they both agreed that the art work in it was pretty awful.” Determined to outdo Cedric Gibbon’s uninspired settings, Minnelli decided on a monochromatic Mesopotamia but also one that was “like Olsen and Johnson in Baghdad . . . very beautiful and chic.”

5

Duquette

let his imagination run wild, conjuring up enough colorful Arabian finery to satisfy a thousand and one nights.

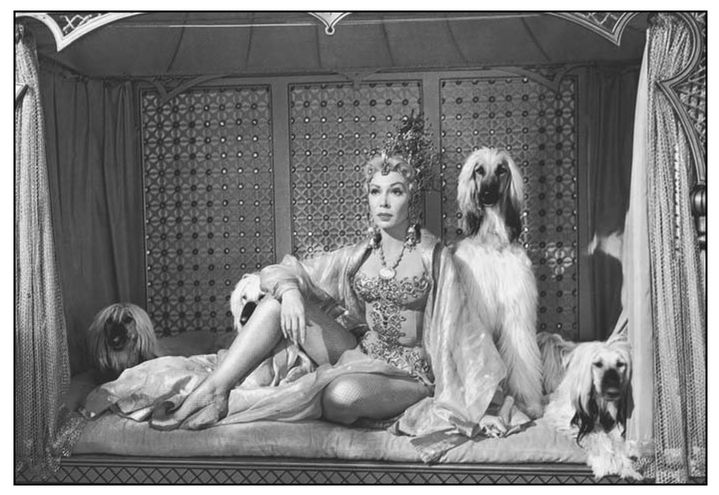

Dolores Gray in Minnelli’s screen version of

Kismet

. As the alluring Lalume, Gray enlivens the film and her sizzling rendition of “Not Since Nineveh” is a knockout. The showstopper also kept things hopping off screen as well. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Kismet

. As the alluring Lalume, Gray enlivens the film and her sizzling rendition of “Not Since Nineveh” is a knockout. The showstopper also kept things hopping off screen as well. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

“Vic Damone looked prettier than the girls in that movie,” recalls assistant director Hank Moonjean, referring to the outlandish ensembles that the former Vito Farinola found himself tarted up in:

The Tony Duquette clothes were something else. Even the dancers couldn’t dance in their costumes. Jack Cole’s dancers had to twirl and spin around a lot but the girls were wearing these huge, elaborate headpieces and every time they spun around, their head gear fell over. Finally, they had to get rid of all those heavy hats and start over. You know, it was my first musical and I remember it in great detail. I couldn’t believe movies were made this way but I learned very quickly.

6

6

Despite the palpable tension on the set, dancer Nita Bieber remembered that Vincente enjoyed a harmonious working relationship with the equally exacting choreographer Jack Cole: “Minnelli really listened to him because Jack Cole had real insight into what was going on with that story and how

the dancers could help bring the whole thing to life. . . . There may have been other problems going on but as I remember it, Minnelli and Jack worked together very well.”

7

the dancers could help bring the whole thing to life. . . . There may have been other problems going on but as I remember it, Minnelli and Jack worked together very well.”

7

Others felt that on

Kismet

, Vincente was anything but a team player. When Keel observed Minnelli reviewing plans for

Lust for Life

on

Kismet

’s clock, Metro’s booming baritone lost all patience with the director’s supreme disinterest. Keel went to Freed and issued an ultimatum: “If Minnelli is on the set tomorrow morning, I’m not on it. So, pull whatever strings you have and get someone else. I am not finishing this picture with Vincente.”

8

Minnelli obediently disappeared, and the equally talented Stanley Donen inherited the project for ten days.

Kismet

, Vincente was anything but a team player. When Keel observed Minnelli reviewing plans for

Lust for Life

on

Kismet

’s clock, Metro’s booming baritone lost all patience with the director’s supreme disinterest. Keel went to Freed and issued an ultimatum: “If Minnelli is on the set tomorrow morning, I’m not on it. So, pull whatever strings you have and get someone else. I am not finishing this picture with Vincente.”

8

Minnelli obediently disappeared, and the equally talented Stanley Donen inherited the project for ten days.

Despite CinemaScope, Eastmancolor, and the talents of Tony Duquette,

Kismet

is an ill-turned rarity: an uninviting Vincente Minnelli musical. As Keel duly noted, much of the blame for the lackluster quality of the picture must rest with Vincente. If Minnelli’s work was indeed the story of his life,

Kismet

would rate only a telegraphic footnote. In fact, in the director’s autobiography, discussion of the film is relegated to a few dismissive paragraphs with a sobering moral included: “The experience taught me never again to accept an assignment when I lacked enthusiasm for it.”

9

Kismet

is an ill-turned rarity: an uninviting Vincente Minnelli musical. As Keel duly noted, much of the blame for the lackluster quality of the picture must rest with Vincente. If Minnelli’s work was indeed the story of his life,

Kismet

would rate only a telegraphic footnote. In fact, in the director’s autobiography, discussion of the film is relegated to a few dismissive paragraphs with a sobering moral included: “The experience taught me never again to accept an assignment when I lacked enthusiasm for it.”

9

ON MAY 20, 1955—three days before Minnelli began shooting

Kismet

—his second child was born. Liza now had a half sister named Christiana Nina, who would later be called Tina Nina. Her formative years would coincide with the busiest period of Minnelli’s career. When Liza was growing up, virtually all of Vincente’s films had been shot on MGM’s Culver City soundstages. During Tina Nina’s childhood, Minnelli was frequently being whisked away to film on location (landing everywhere from Paris, France, to Paris, Texas). Although Vincente obviously loved Tina Nina, and indulged her in much the same way he had Liza, his time with his youngest would be limited.

Kismet

—his second child was born. Liza now had a half sister named Christiana Nina, who would later be called Tina Nina. Her formative years would coincide with the busiest period of Minnelli’s career. When Liza was growing up, virtually all of Vincente’s films had been shot on MGM’s Culver City soundstages. During Tina Nina’s childhood, Minnelli was frequently being whisked away to film on location (landing everywhere from Paris, France, to Paris, Texas). Although Vincente obviously loved Tina Nina, and indulged her in much the same way he had Liza, his time with his youngest would be limited.

“Liza was much more at ease, much closer to daddy than I was,” the adult Tina Nina recalled. “She had her mother, [and] although Judy had her ups and downs, Liza had her on a pedestal. But daddy was her stability and Liza was practically in love with him. She worshipped him and he worshipped her. He didn’t have a family, other than an aunt. All he had was Liza. . . . He was alone and she was alone. They only had each other.”

10

10

The bond between Vincente and Liza was so strong and so special that Tina Nina, like Georgette before her, may have felt like an intruder at times. How could Minnelli’s “other” daughter ever hope to compete with Liza, who

was not only a multimedia goddess in the making but, without question, the center of attention in Vincente’s life. Sure, Tina Nina would slip into Liza’s miniature Metro ensembles and attempt a Cyd Charisse-style pirouette, but this was just “play time.” It almost certainly didn’t fulfill the same need that it did for her older sister—or their father, for that matter. Vincente and Liza were dependant on the fantasy as a means of psychological escape, whereas Tina Nina, the daughter of practical, down-to-earth Georgette, was simply having a bit of fun.

was not only a multimedia goddess in the making but, without question, the center of attention in Vincente’s life. Sure, Tina Nina would slip into Liza’s miniature Metro ensembles and attempt a Cyd Charisse-style pirouette, but this was just “play time.” It almost certainly didn’t fulfill the same need that it did for her older sister—or their father, for that matter. Vincente and Liza were dependant on the fantasy as a means of psychological escape, whereas Tina Nina, the daughter of practical, down-to-earth Georgette, was simply having a bit of fun.

Vincente made every attempt to make Tina Nina feel loved, and he went out of his way to bring his two daughters together. After Judy married third husband Sid Luft in 1952, Liza didn’t seem to mind sharing her mother with half-sister Lorna or half-brother Joey. But sharing her beloved father with another child was another matter entirely. As Tina Nina recalled: “Daddy and Liza were so close that she would get jealous when I arrived. Sometimes she pretended to be sick. Then daddy rushed into her room and comforted her. I remember her lying in bed and crying, ‘Daddy, you don’t care about me. You only care about Tina Nina. I’m jealous of Tina Nina.’ I felt so guilty.”

11

11

Vincente would remember Tina Nina as “the brightest spot” in his four-year marriage to Georgette. While an introvert like her husband, The Second Mrs. Minnelli was grounded and pragmatic. Vincente, on the other hand, was dreamy, restless, and detached. At times, it seemed as though their daughter was one of the few things they had in common.

22

Maelstroms and Madmen

IF MINNELLI HAD SPED THROUGH the filming of

Kismet

with nearly complete disinterest,

Lust for Life

would engage him on every level. “It was the most thrilling and stimulating creative period of my life,” Vincente would later say of the production.

1

The director’s affinity for his subject, Vincent van Gogh, would result in one of Minnelli’s most moving and psychologically intimate films. While it may be something of a stretch to draw parallels between Vincent van Gogh’s postimpressionist innovations and Vincente Minnelli’s unconventional filmmaking techniques, artist and director clearly had more in common than their first names.

Kismet

with nearly complete disinterest,

Lust for Life

would engage him on every level. “It was the most thrilling and stimulating creative period of my life,” Vincente would later say of the production.

1

The director’s affinity for his subject, Vincent van Gogh, would result in one of Minnelli’s most moving and psychologically intimate films. While it may be something of a stretch to draw parallels between Vincent van Gogh’s postimpressionist innovations and Vincente Minnelli’s unconventional filmmaking techniques, artist and director clearly had more in common than their first names.

Other books

The Cay by Theodore Taylor

Objects of Worship by Lalumiere, Claude

The Long Fall by Lynn Kostoff

Deadly Satisfaction by Trice Hickman

Highland Tides by Anna Markland

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) by Mark Twain

Crimson Cove by Butler, Eden

Black Christmas by Lee Hays

Wildfire on the Skagit (Firehawks Book 9) by M. L. Buchman

After the Last Dance by Manning, Sarra