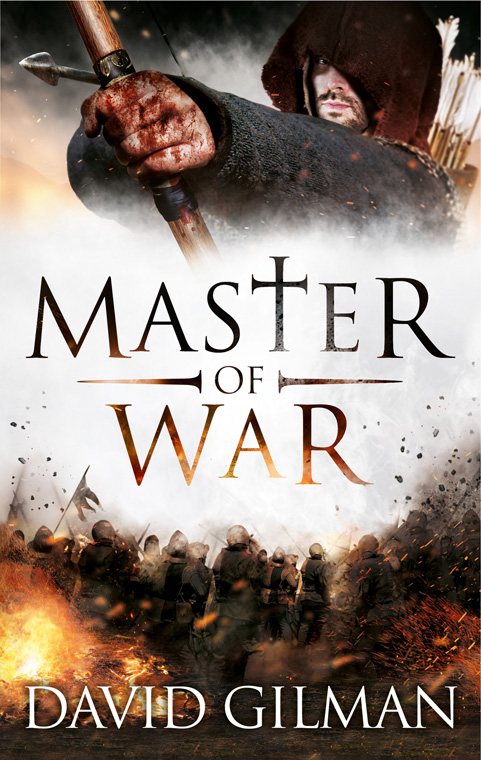

Master of War

Authors: David Gilman

For Suzy,

as always

The Blooding

1

Fate, with its travelling companions Bad Luck and Misery, arrived at Thomas Blackstone’s door on the chilly, mist-laden morning of St William’s Day, 1346.

Simon Chandler, reeve of Lord Marldon’s manor and self-appointed messenger, bore his master’s freeman no ill will. A warning to the young stonemason of the writ issued for his brother’s arrest would stand him in good stead with his lordship and make the reeve appear less grasping than he was. A chance for the boy to run rather than hang. And hang he surely would for the rape and murder of Sarah, the daughter of Malcolm Flaxley from the neighbouring village.

‘Thomas?’ Chandler called, tying his horse to the hitching post. ‘Where’s that dumb bastard brother of yours? Thomas!’

The house was one room deep, twenty-odd feet long, its cob walls made of clay and straw mixed with animal dung, the steep pitched roof thatched with local reed, now aged and smothered in moss. Smoke seeped through an opening in the roof. Chandler stooped low beneath the eave to bang on the iron-hinged door. A figure emerged from the mist at the side of the cottage.

‘You’re about early, Master Chandler,’ said the young man cradling an armful of chopped wood. He looked warily at Lord Marldon’s overseer. There was no good reason for the man to be there. It could only mean trouble.

Thomas Blackstone stood a shade over six feet and, apprenticed in the stone quarry since the age of seven, had the build of a grown man who used his body tirelessly doing hard labour. His dark hair framed an open face with no meanness of spirit reflecting from his brown eyes. Lean like the rest of him, it was weathered to a colour that almost matched his leather jerkin. It gave him the look of a man older than his sixteen years.

‘I’m here to warn you. There’s a warrant of arrest for your brother. The sheriff’s men are on their way. You don’t have much time.’

Blackstone peered into the rising mist; another hour and the morning sun would burn it away. He listened for the sound of hoof beats. The horsemen would come down the rutted track; its flint would ring from the impact of steel-shod hooves. It was quiet except for a morning cockerel. The cottage lay beyond the edge of the village; if he had the desire to run he could have his brother into the forest and over the hills without being seen.

‘What charge?’

‘Rape and murder of Sarah Flaxley.’

Blackstone felt his stomach lurch. His face betrayed nothing.

‘He’s done nothing wrong. There’s no need for us to run. Thank you for your warning,’ said Blackstone, laying down the cut firewood next to the front door.

‘Christ, Thomas, I know his lordship would not want any harm to befall your brother. You’re his keeper, and his lordship has always looked kindly on you both since your father’s death, but you will be held equally responsible. You will hang with him.’

‘Is your cousin still seeking to farm here? It would be convenient if Richard and I took to the hills as fugitives. Our ten acres would suit him.’

Chandler was stung by the truth of the accusation. ‘You’re a fool! Lord Marldon can’t protect you from this.’

‘My lord has always said a man has nothing to fear if he is innocent.’

Chandler pulled the reins free from the post and climbed into the saddle.

‘You remember Henry Drayman?’

A man disliked across half a dozen villages in the county. A brute of a man in his twenties who would gamble for any easy victory, be it cock-fight or throw of dice. Blackstone’s brother had repeatedly beaten him in archery competitions, but Drayman’s humiliation had been complete this past Easter when Richard had beaten the older man in the wrestling contest. Bested by a boy nearly ten years his junior, he had sworn revenge, and now, somehow, he was inflicting it.

‘Your freak of nature brother will be on the end of a rope by tomorrow. He’ll bray in terror. The dumb bastard.’

Blackstone took a step forward and effortlessly grabbed the horse’s reins. He twisted them, trapping Chandler’s hands in a leather burn. The man winced.

‘I respect your office, Master Chandler. You serve his lordship with diligence, but I would beg you to assure him that neither I nor my brother have brought any shame to his great name.’

He released his grip. Chandler turned the horse away.

‘They caught Drayman with her ribbons. Her body was found in her father’s cornfield. That’s where you used to take her, isn’t it? And your brother? Christ, the whole damned village fornicated with her, but Drayman turned approver before they hanged him yesterday.’

Blackstone knew there could be no escape from the sheriff’s court now. A man condemned to death could accuse his enemies by way of appeal – of implicating another in his crime by approval. Torture was illegal under King Edward III, but those with the power and authority of local law enforcement would never shy away from using it to secure a confession. After a week tied naked to a stake, soiled by his own waste, starved of food and denied water, the beating at the hands of the sheriff’s men had finally broken Drayman’s mind and loosened his tongue. His life was forfeit, but sufficient cunning still lingered behind the pain and suffering. He would leave this world taking another with him. An enemy. The one who had humiliated him; whose name was etched into his heart as if the stonemason himself had chiselled it there.

Chandler smiled. ‘The price of wool is going up. My cousin will have his sheep on your land in a week.’

He spurred the horse away.

Woodsmoke trapped by the mist snaked away, searching for its escape. There was none. Blackstone knew the dead man had wreaked his revenge. The sound of horse’s hooves clattered towards him.

It was too late to run.

Blackstone had time to warn his brother not to resist the armed men who came to arrest them. The boy made a guttural groaning sound, his way of confirming his understanding. His brother and guardian was the only source of comfort the deaf-mute boy had had in his life. He was little more than a beast of burden to anyone else and the butt of practical jokes and torment. Were it not for Thomas, Richard Blackstone could have used his strength to fight and kill his tormentors. The boy’s size and that great square skull with nothing more than a down-like covering confirmed to everyone in the surrounding villages that the boy was indeed a freak of nature. His crooked jaw gave his face a permanent idiot grin.

They had cut his mother open to lift the child from her and she was dead within hours from the loss of blood. A huge child at birth, he uttered no cry and showed no sign of reaction to the torchlight being crossed in front of his face. The village midwife who helped Annie Blackstone bring this hulking creature into the world said that the silent, mouthing infant should be left in the cold night air to die. Tortured by the loss of his wife, Henry Blackstone agreed. He already had a two-year-old infant to care for. This monstrous baby would be left to nature. It was a bitter wind that blew from the east that autumn of 1332. The barley crop had failed again, the drought suffocated the land and cold air settled at night into an unseasonable frost to cramp a man’s starving body. By midnight the moon’s glow illuminated the sparkling ground. The abandoned child’s father walked out to the corn stubble and found his son still alive. A ring around the moon shimmered, a sign of heavenly marriage between sky and earth, and Henry Blackstone lifted the child from the cold ground. His wife had taught the warrior that tenderness would not weaken him, and her love had weaned him from the brutality of war. He lifted the cold body and held it close to his naked chest, wrapping it in a blanket and settling more logs on the fire.

It was his child. It had a right to life.

The sheriff’s men took the brothers, tied and manacled in the back of a cart, through the hamlets and villages to the market town. The iron-rimmed wheels rumbled across the rutted marketplace towards the town’s prison cells, past Drayman’s body dangling from the gibbet. The crows had already taken his eyes and the pecked flesh was down to the bone in places. His tongue had been torn away by voracious beaks.

The soldiers threw the brothers into wooden cages in the coldest corner of the sheriff’s courtyard where the sun’s warmth could not penetrate. The boy muttered an almost animal-like whimper, a question to his brother.

Over the years Blackstone and his father had developed a means of communicating with the blighted sibling by using simple gestures to calm and explain events. Where he should go, what he should do, and why strangers stared and children tugged his shirt. The local villagers had ceased tormenting him when the novelty wore off and the boy’s strength and skill with a bow became apparent at the county fairs. They might call him the village idiot, but he was

their

village idiot and he brought victory. They lived in hovels, died young through disease, hard work and war – but Richard Blackstone, the freak child, gave them with his success the only status they would know.

There was no dulled intelligence inside the lumbering boy; his eyes and brain were as sharp as a bodkin arrowhead. The fact that he was trapped in silence was no indication that his mind was disabled as well as his speech and hearing. He kept a constant watch on his older brother and took guidance from his instructions, which was why he always walked a pace behind Blackstone’s left shoulder.

Now he endured the guard’s taunts as they jabbed their spears through the bars, forcing him into the corner of the cage, but he could not escape the man who urinated over him as he cowered back from the spear points. He could see Thomas’s face contorting in anger as he gripped the bars, his teeth bared.

‘Leave him alone, you bastards!’ Blackstone yelled and earned a blow from the dull end of a spear shaft.

However, there was little sport to be had from tormenting the creature and the guards soon went back to their posts. The piss-stinking boy looked to his brother and understood the look of anguish on his face, and his helplessness. Richard’s crippled jaw opened into a wider smile. These events were nothing new. He dropped his hose and bared his arse in contempt for his gaolers.