Masterpiece (24 page)

Authors: Elise Broach

“Liesl? It’s Denny. How are you, my dear? Yes, still as planned, into Frankfurt. I’ve purchased an open ticket because I’m not certain what day I’ll be traveling. You’ll arrange my transportation from the airport?”

Denny paused, listening. “Good. Yes, that’s right. I’ll be in touch. See you soon, Liesl.”

So that was it, Marvin thought. Denny and Christina must be planning to take the drawings out of the country. “Liesl” had a foreign sound to it.

Marvin watched Denny decant a bottle on the desk and pour an amber liquid into a squat crystal glass. He turned to the drawings.

“To Virtue,” he whispered huskily, raising the tumbler, and Marvin thought Denny sounded as if he was

about to cry. “And to Virtue’s master, the astounding Albrecht Dürer.”

He drained the glass and set it on the desk. As Marvin watched, he gently concealed the drawings under several sheets of the protective paper, then left the room.

Marvin crawled across the table to where the drawings lay. As he crouched there, wondrously close to them, he was filled with confusion. It was impossible to think of Denny and Christina as thieves. They were devoted to Dürer’s art. Marvin pictured the two of them in Christina’s office, interrupting each other with their passion for the drawings. Was it all an act? None of this made sense.

Then he remembered something Denny had said about people who stole works of art: that sometimes, they did it for love.

A

s Marvin huddled there, inches from Dürer’s tiny masterpieces, a thin, sharp prick of resolve began to form inside him. He had to do something. But what? There had to be some way to stop this terrible theft. If only James were here! He needed his friend’s help now more than ever.

Marvin scurried down the table leg and across the rug to the desk. Swiftly, he climbed up and crossed its smooth expanse to the window ledge. The glass panes were filmy with winter grit, but Marvin could see the length of the street quite clearly. It was a tree-lined block with handsome brick and stone town houses on either side, interspersed with shops and restaurants. Not dissimilar to the Pompadays’ own neighborhood, Marvin thought. So perhaps they were still on the Upper East Side somewhere. This notion comforted him, even though a few city blocks would be a month’s journey from a beetle’s perspective.

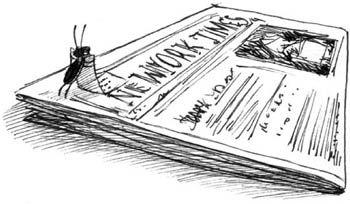

He scanned the desk desperately, trying to think what to do next. There was an upright metal tin of pencils and pens, a pad of paper, a small tray of paper clips and rubber bands, and a sheaf of envelopes and newspapers. Marvin crawled over to the stack of papers.

It must be Denny’s mail

, Marvin thought. He knew a little about the human system of mail, because Papa had explained it to him several weeks ago, when, tragically, Cousin Buford had been scooped up with Mrs. Pompaday’s real-estate contracts, sealed inside a flashy orange and purple Federal Express envelope, and mailed to one of her clients. When Marvin asked where he’d been sent to, Papa said that the address was written on the front of the envelope, though the beetles had no way of deciphering it. (Comfortingly, Papa did explain that, wherever Buford was headed, he was sure to arrive by 10:30 the next morning.) The family could only pray he’d survived the journey and made a new life for himself somewhere in the city. Privately, Marvin had his doubts about Buford’s ability to make a sandwich, much less a new life for himself. But there was no point in dwelling on what couldn’t be helped.

Thus Marvin knew that the writing on the envelope told the mailman where to deliver it. He hesitated at the edge of the stack. One of the newspapers had a white label stuck to it. Could it be the address of this apartment? The place where Dürer’s

Virtues

were being held captive? Marvin considered this possibility. If there was some way to get the mailing label to James, he’d at

least know where to look for the stolen drawings . . . as long as he got the address before Denny packed up the drawings and left the country.

It was a long shot, but the only idea he had at the moment, and it was certainly better to do

something

than to sit there fretting while the drawings disappeared forever.

He crawled across the thin newsprint to the label. It had to be unstuck somehow. Careful to protect the lines of type, he gently chewed the foul-tasting yellow glue that gummed the label to the paper. Using his legs to lift and tug it, he eventually dislodged the whole thing.

Pleased with himself, Marvin dragged the label over to an empty surface of the desk. It was slightly tatty at the edges and wet from his chewing, but it still held three complete lines of black letters. He spread it flat and set about meticulously folding and rolling it, exactly as he did with his blanket and towel whenever the beetles

went camping. When he’d reduced the label to a tidy bundle that was about as long as he was, he scanned the desktop for something to tie it with.

He caught sight of Denny’s jacket, flung over the chair. A scattering of Denny’s gray hairs clung to the shoulders, just as Marvin had hoped. He crawled over to

fetch one and then used it to tie the rolled label to his underbelly, cinching the strand of hair like a belt.

As one would imagine, this made it very difficult indeed for Marvin to walk. He waddled back to the stack of mail and sat down under the corner of the newspaper, heaving with exhaustion. Now he just had to think of a way to get the label in James’s hands.

His thoughts were interrupted moments later when Denny appeared in the doorway of the study, speaking urgently into his cell phone.

“What? What do you mean? Christina, I don’t understand.”

Christina! His accomplice. Marvin shuddered with disgust. How had he let himself become so fond of her?

“What happened?” Denny continued. “They did? Just the matting? Oh, of course, with the tracking device. My dear, calm down, it’s difficult to understand you.”

Marvin scooted out from under the newspaper to hear him better. Why was Christina upset? Their plan had worked perfectly.

“Well, it’s a terrible shame, but why are you so—”

There was a long silence, and Denny leaned against the table, listening intently. He rested one hand inches from the drawing of

Justice

, tapping the table lightly. Suddenly he sucked in his breath.

“No! The

real

Dürer? Christina, you must be mistaken.”

Marvin scooted out from under the pile of mail,

thoroughly bewildered. Of course it was the real Dürer, they’d stolen it themselves. Very faintly, he could hear Christina’s high, frantic voice on the other end of the line.

“No, I was in the gallery yesterday, and I didn’t notice anything amiss. Of course I wasn’t looking closely, since you’d wrapped it up yourself. You’re right, it was confusing, but my dear . . . I just can’t believe it. Are you sure?” Denny paused.

So Christina hadn’t known! So many feelings raced through Marvin that he barely remembered to hide himself when Denny walked toward the desk to get his coat. In the shadow of the newspaper, he slumped in relief. Christina was not involved. Her love for the drawings was real. Her friendship with James and Karl was true.

“Yes, yes, I’ll come over at once,” Denny said. “I need to see this for myself.” Marvin could hear another flood of tinny commentary through the phone, and Denny waited, one hand on his coat.

“It’s too much to contemplate, that

Fortitude

would be gone now too.” Denny paused in heavy silence, but the idle movements of his fingers over his coat betrayed his calm. Marvin twitched, furious. What an act this was! “If you’re right, I must contact my director and the Getty’s board of trustees as soon as possible, of course.”

Marvin could hear the anguished tones of Christina’s response, and remembered that

Fortitude

had been on loan from Denny’s museum. It didn’t even belong to the

Met. That would make Christina’s horror and guilt all the more keen, he knew.

Denny listened for a minute, then said, “No, no, I saw the care you took, I was there with you. You mustn’t be so hard on yourself, Christina. I still—to be completely frank, I still don’t understand how it could have happened. James’s likeness was remarkable, but . . . you’re certain the original is gone?”

Oh, what a liar he was! Marvin could barely contain himself.

“Yes, yes. I’m so sorry, my dear. It’s just unthinkable. Have you notified museum personnel? The police?” Denny waited. “All right, that makes sense. I’ll come immediately, and we’ll do it together. Perhaps you’re mistaken after all, Christina. Oh . . . James is there now?” He frowned slightly. “He did? Hmmm . . . yes . . . I see.”

Marvin felt a wave of gratitude sweep through him. James was there! If only he could get to James, he would figure out how to explain everything. There had to be a way to save Dürer’s lovely masterpieces before they were lost forever.

“I’ll meet you in your office in twenty minutes,” Denny continued. “We’ll speak to your director together.” He clicked off his phone and reached for his jacket.

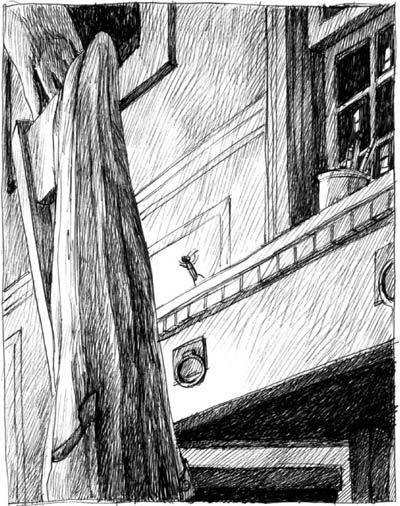

This was his chance, Marvin realized. As Denny gathered his coat from the chair, Marvin ran awkwardly to the edge of the desk, careful not to bump the rolled label that was affixed to his belly, and dove straight through the air toward one sleeve.

His body was much heavier than usual, and he barely reached his target. Desperately pedaling his legs, he clutched the fabric just as Denny yanked the jacket over his shoulders.

Denny turned to the table, smiling down at the drawings. “And now, ladies, I can’t very well leave you out in the open for anyone to see.”