Masterpiece (21 page)

Authors: Elise Broach

He was certain that he was looking at the original. As faithfully as he had followed Dürer’s lines, as carefully and reverently as he’d copied each whorl of hair and bulge of sinew, Marvin knew that the intricate strokes in the artwork before him weren’t his. A drawing was

as personal as handwriting. Yours might look similar to someone else’s—even identical in the eyes of a stranger—but you could always recognize your own.

Marvin crawled out from under James’s collar. He was fully exposed to the light and air, directly in the sightlines of the surrounding museum-goers, but he couldn’t help himself. This was the original, as dignified and melancholy and fully Dürer’s as it had ever been.

His mind raced. Why was the Dürer drawing hanging here instead of the copy? Where was his own drawing? He gripped James’s jacket, trying to piece together what could have happened. Christina had said the real drawing was in the museum director’s office, in a vault. How could this be? Marvin felt a growing sense of dread.

He began to run back and forth along the edge of James’s collar, frantic. The FBI agent was coming to take this drawing, in nearly two hours’ time. What if Christina had made a mistake? What if she’d somehow mixed up the two pictures?

There was a tracking device, Marvin reminded himself, trying to calm down. The FBI would be monitoring that. But now he had to consider the possibility that the tracking device was about to be affixed to the Dürer original by mistake. And suddenly, Christina’s warnings about the danger of the plan—the chance that the drawing would be truly stolen and lost forever—filled his head like a drumbeat. That had been alarming enough when Marvin believed his own drawing was at risk. But now it looked like the

real

Dürer might be taken from

the museum and whisked into that strange, foggy world of art thieves and stolen masterpieces.

Above him, Karl and James seemed not to suspect a thing. “It’s fantastic, James,” Karl was whispering. “Everything about it looks real.”

That’s because it IS real!

Marvin wanted to shout. He scuttled back into hiding before Karl could see him, awash in panic. How could he tell them? The real Dürer

Fortitude

was about to be stolen, just like the other three

Virtues

!

“Look at the detail,” Karl continued. “To see a drawing, really see it, takes time.”

Yes!

Marvin thought.

Look at it, James. Look at it and you’ll know

.

But James only stood quietly before the drawing, gazing at it steadily. Finally, Karl said, “We should go. You’ll see it again before too long.”

No!

Marvin screamed silently.

“I hope so,” James said uncertainly. He shifted from one foot to the other, hesitating.

Please, James

, Marvin prayed.

It’s not my drawing

.

“Come on, buddy.” Karl clasped James’s shoulder.

As James started to turn away, all Marvin could think of was the drawing. He couldn’t bear to leave. Not knowing what else to do, he rushed to the tip of James’s collar, pointed himself toward the wall, and jumped into the void.

M

arvin plummeted headlong through space for several long seconds.

Thump!

He crashed into the floor of the gallery, rolled twice, and came to a halt. Fortunately, the room’s low-pile gray carpet softened his landing. He was a little dazed but none the worse for wear. Shoe-clad feet milled around him, and James’s blue sneakers were fast disappearing in the distance. He knew it was suicide to linger out in the open. He crawled as fast as he could to the wall and waited near the scuffed baseboard.

Marvin had to make his way to the drawing, but it seemed too risky to climb the wall when so many people were looking at the pictures. He knew that his black shell would be hard to miss once he started the trek across the expanse of wall. Though his stomach clenched over the danger facing Dürer’s drawing, he decided there was nothing to do but wait till the gallery cleared out. In the flurry of closing, he hoped he could

make his way to

Fortitude

unnoticed, before the FBI agent did.

The evening passed quickly. To take his mind off his fears, Marvin occupied himself with people-watching, which was one of his favorite pastimes anyway. He counted the different types of shoes that strolled past his hiding place: 12 black loafers, 6 brown loafers, 4 stilettos, 8 black lace-up shoes, 6 pumps, 4 hiking boots, 8 dress boots, 11 sneakers (and one cast). He tried to predict how long people would linger in front of the pictures based on their type of shoe. The pumps and black loafers won, with the hiking boots a close second. The sneakers were divided between those who stayed longer than anyone (college students, Marvin decided), and those who rushed off with barely a glance (children).

After a couple hours of this, Marvin was starving. The floor was disappointingly free of litter, probably due to the museum’s prohibitions on food and drink. But a few minutes later, a woman walked by pushing a stroller, and Marvin was delighted to see a Cheerio tumble off her toddler’s lap. He studied the movements of the crowd thoroughly before making a mad dash to retrieve it. Then, just as he and Elaine did at home, he wedged his head and forelegs through the hole in the Cheerio, pushed off with his rear legs, and sent it rolling like a hoop toward the baseboard, whisking him to safety. When he reached the edge of the carpet, he extracted himself and settled down to dine. The Cheerio

was a little stale, but sweet and crunchy nonetheless: a very satisfying evening meal.

Finally, the speaker system chimed, and a woman’s voice echoed through the gallery: “The museum will be closing in fifteen minutes. Please proceed to the exits now.”

Marvin hesitated only a moment, making sure that people were really turning to leave, then scurried up the wall as fast as he could. When he reached the corner of

Fortitude

’s wooden frame, he paused just long enough to look at the drawing, admiring the delicacy of lines that weren’t his own. Then he ducked out of sight behind the lower left corner of the frame.

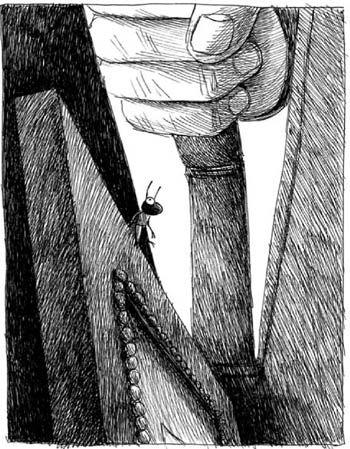

He didn’t have long to wait. A moment later, he heard swift footsteps approach the drawing, then felt the picture being lifted from the wall. He held fast as the

frame was shoved hastily into some kind of canvas bag, pitch-black inside. Marvin could see nothing but dark fabric all around him. He looked up, and through the narrow opening at the top, he caught sight of thick fingers gripping the handle, the knuckles sparsely covered in hair. The bag swayed and bounced for a few minutes; then, with a gentle thud, it stopped.

This must be the supply closet, Marvin realized. He heard the rustle of cloth and inched up the side of the frame. The darkness of the closet was no impediment to

Marvin, who was well used to navigating at night. He could see a short, stocky man moving quickly and confidently, casting aside a navy blue guard uniform.

Suddenly, the frame was snatched from the canvas bag and laid facedown. Marvin had to reposition himself on its side, flattening his body. He’d forgotten this part of Christina’s plan. The frame was about to be disassembled. He had to keep out of sight. He heard the

clip, clip

of wire cutters removing the hanging apparatus. A knife flashed above him, perilously close. He shrunk away from the blade that glided expertly through the backing of the picture in a crisp rectangle.

Marvin prayed he wouldn’t be knocked off. The next few minutes were critical. If he got bumped or shaken loose—or worse yet, if the man saw him and swatted him away—who could say where

Fortitude

would end up?

He heard the tear of paper. Abruptly, a penlight flashed in the darkness, sending a narrow white beam onto the back of the picture.

Marvin dodged out of sight, terrified. Now he could see the man, his forehead creased in concentration. He had dark hair and an otherwise bland appearance. He could be anyone, Marvin thought—probably an advantage for an undercover FBI agent. The man grunted, tearing off the rest of the backing until Marvin saw the pale matting. Just as the man was about to lift the drawing from the frame, Marvin leapt onto the matting. It felt firm beneath his legs. When he peered over the edge, he saw the yellowed, ancient paper that was surely

the reverse of Dürer’s masterpiece. He could smell it too—the musty scent of centuries.

Holding the matting gingerly with one hand, the man set down the penlight. Marvin cowered out of sight, watching him remove something tiny and silver from his inside pocket. It must be the microchip, he realized. The man lifted the matting and turned it quickly and expertly, making a small cut with his knife, while Marvin hugged the edge. It was like surgery, Marvin thought, this delicate task of embedding the microchip in the side of the matting, where it wouldn’t be seen. After several minutes of manipulation, during which Marvin could hear the man’s heavy, impatient breathing, the penlight clicked off.

The microchip was in place.

Marvin barely had time to secure himself against the back of the matting when a piece of something stiff was pressed against his shell. The drawing swung through the air and glided smoothly into a small, tight space.

It must be the jacket pouch, Marvin realized.

Fortitude

was ready for its journey.

It was completely dark inside the jacket, and even Marvin, who was very accustomed to small, dark places, felt a wave of claustrophobia. He remembered the time he and Elaine had gotten stuck in Mrs. Pompaday’s eyeglass case when she’d snapped it shut one evening; how he’d panicked and pushed futilely against the felt walls, and Elaine had made fun of him for almost throwing

up. Fortunately, Mrs. Pompaday had decided to watch a rerun of one of her shows, and it wasn’t long before the case was opened again. (Even more fortunately, she was so absorbed in the television that she didn’t notice two shiny black beetles making their escape.)

Now, Marvin felt the jacket sway with the movements of its owner. He could tell when the man left the closet; when he paused to make sure he hadn’t been seen; when he strode through the hallway and tripped briskly down the museum’s central staircase. Fragments of Cheerio sloshed uncomfortably in Marvin’s stomach.

Bouncing along against the man’s warm, substantial chest, Marvin could hear the noises of the crowds through the thick cloth. He felt the change in temperature as they exited the Met into a chilly New York evening. A car door opened and slammed shut. The man mumbled an address to someone, then Marvin heard the rapid beeps of a cell phone keypad.

He strained to follow the conversation.

“Yeah, it’s done,” the man said. “Nope. I’ll be there in twenty minutes. What’s the room number? Okay, see you then.”