Masters of Death (19 page)

When Hitler met with Göring and other high Reich officials at Wolfschanze in East Prussia on 16 July 1941 to discuss Eastern policy, he referred specifically to Stalin’s partisan-warfare instructions. In the notes of the meeting kept by his private secretary and Party Minister Martin Bormann, Hitler endorsed the vision he shared with Himmler of what he called “a Garden of Eden” in the East. “On principle,” he said, “we have now to face the task of cutting up the giant cake according to our needs, in order to be able: first, to dominate it; second, to administer it; and third, to exploit it.” He would take “all necessary measures — shootings, resettlements and so on”— to accomplish that end, a “final settlement.” Stalin’s partisan order, he pointed out, gave the game away: “It enables us to eradicate everyone who opposes us. . . . Naturally, the vast area must be pacified as quickly as possible; the way to do that is to shoot dead anyone who even looks at us sideways.”

As far as Hitler was concerned, the Jews were implacably hostile; Stalin’s partisan order gave him an excuse to murder them down to the last woman and child. (Hitler was even more specific in a meeting with Slovakian defense minister Sladko Kvaternik six days later. The Russian people were “bestial,” he told Kvaternik; the only thing to be done with them was to “exterminate them,” to “do away with them.” The Jews were “the scourge of mankind”; Russia had become a “plague center”; “if there were no more Jews in Europe, the unity of the European states would no longer be disturbed.” To this outsider Hitler still spoke of sending the Jews of Europe “to Siberia or Madagascar,” but he knew full well that Madagascar was no longer an option and Siberia a cold mass grave.)

Himmler, twenty miles away at his lakeside headquarters, did not find it necessary to attend this Führer conference even though it concerned his responsibilities. He had already discussed those responsibilities with the Führer. The next day, 17 July 1941, Hitler decreed that Himmler’s authority in police matters in the occupied territories was fully equivalent to his authority in Germany itself, thus bypassing the appointed civil authorities throughout the East. In Germany Himmler was responsible for identifying and eliminating internal enemies; from the Nazi perspective, the equivalent of internal enemies in the Ostland

24

and the Ukraine was first of all the Jews.

The authority over the East that Hitler assigned to Himmler was fundamental to laying the foundation for their Garden of Eden. As a result of their discussions, Himmler could prepare to turn in earnest to that work, moving beyond decapitation to extermination. That same day, 17 July 1941, the Reichsführer appointed as his deputy for

Wehrbauern

settlement the SS and Police Leader for the Lublin district, Brigadeführer Odilo Globocnik. Three days later Himmler flew to Lublin to meet with his appointee.

Globocnik was an operator, a beefy Austrian with combed-back hair and a fleshy but youthful face. Rudolf Höss, the tough-minded commandant of Auschwitz, called him “a pompous ass who only understood how to make himself look good.” Globocnik was born in Trieste in 1904 into a family of minor bureaucrats of Slovenian descent who considered themselves German. Like Himmler, he missed serving in the Great War, but unlike Himmler he gained personal experience with violence in the Austrian Freikorps and the SA. He was an energetic but uneducated construction foreman, active in the Nazi Party in and around Vienna as early as 1922, anti-Semitic and fanatic. His work for the party won him appointment as a deputy Gauleiter in 1933, but because the Nazi Party was illegal in Austria, he was imprisoned four times between 1933 and 1935 for criminal party activities. Working in construction gave him easy access to explosives, which he procured and distributed; one of his convictions was for participating in a bomb attack that killed a Jewish jeweler (and probably also involved robbery). He joined the SS in 1934. His covert activity against Austria before Germany annexed it in 1938 earned him promotion to Gauleiter of Vienna, but in January 1939 his speculations in illegal foreign exchange led to his being stripped of his post and of party honors. “He made such a mess and caused such chaos,” says Höss, who was jealous of Globocnik’s influence, “that they had to recall him.” Himmler punished the Austrian by demoting him to the rank of Unterscharführer — corporal — and assigning him to the Waffen-SS. But Globocnik was too useful—and too enthusiastic an apostle of Himmler’s visions — to waste in the front lines, and in 1939 the Reichsführer-SS pardoned him, promoted him to Brigadeführer and assigned him responsibility for Lublin province.

Himmler liked Globocnik; he called him Globus. It was Globus who had thought up the Panama Canal–scale antitank-ditch project that Himmler had proposed to von Brauchitsch in 1940. The ditch was supposed to serve as a military bulwark against the Red Army and put all 2.5 million Polish Jews to work. It was planned to be fifty yards wide, with its trough descending five feet below the water table. Globocnik dispatched some thirty thousand Polish Jewish prisoners to begin digging it. By 1941 only eight miles had been finished; they were amateurishly constructed and militarily superfluous.

Himmler flew to Lublin on 20 July 1941 to tour the areas Globocnik was promoting for pilot-scale

Wehrbauern

settlements: the Lublin district itself and a picturesque valley in southeastern Poland around the old quasi-German colony of Zamosc. (Ironically, the next valley westward from Zamosc, the even larger valley of the San River, had been the SS’s choice for a Jewish reservation centered on the town of Nisko when confining the Jews to a reservation was still being considered. As Eichmann remembered a visit to Nisko in October 1939: “So we came finally to Nisko on the San. . . . We came to that place, saw an enormous territory, a river, villages, markets, little towns, and we said to ourselves, that’s the reality, and why should one not resettle the [Nisko] Poles, where indeed so many were unsettled anyway, and then give the Jews a large territory here?”) Höss writes that Globocnik “promised Himmler that within one year he was going to bring in fifty thousand new [German and ethnic German] settlers as a pattern and example for the future, when huge settlements were supposed to be created farther in the East. All the necessary things, such as the cattle and the machinery, were supposed to be supplied by Globocnik as soon as possible.” Himmler further assigned Globocnik responsibility for organizing the extermination of the Polish Jews.

After touring Zamosc on 21 July 1941, Himmler approved what he called in his action order “a major settlement area in the German colonies at Zamosc” under the umbrella of his “Quest for German Blood.” Richard Breitman summarizes Globocnik’s comprehensive commission:

Himmler authorized Globocnik to carry out a geological and geographical survey of the Eastern territories as far as the Ural Mountains, to plan police strongholds scattered throughout that vast area, to construct model farms with up-to-date living quarters and equipment, to recondition existing farms, and, in a nice anthropological touch, to study ancient national costumes to be worn by German immigrants. Globocnik was allowed to recruit a staff of architects, interior decorators, contractors, drainage experts, surveyors and historians.

To support this fantastic project Himmler authorized Globocnik to establish a concentration camp for 25,000 to 50,000 prisoners in a southeastern Lublin suburb, with workshops to supply the

Wehrbauern

settlements with clothing and equipment. The camp would become Majdanek; the fact that it was sited within view of Lublin Castle in the city’s blufftop medieval center indicates that it was not originally planned to be a death camp. When Höss’s superior sent the Auschwitz commandant to Lublin to collect supplies from Globocnik for Majdanek, Globocnik spun out Himmler’s vision to Höss as if it were his own:

He acted incredibly important as he used Himmler’s order to build new police bases [i.e., fortified Wehrbauern settlements] in the newly conquered areas. He developed fantasy plans for bases extending as far as the Ural Mountains. No difficulties existed as far as he was concerned. He would just dismiss any objection with a sweep of his hand. He wanted to exterminate the Jews right then and there and save only those he needed for building the police bases. . . . In the evenings by the fireplace he spoke about these ideas in his Viennese accent so casually that they seemed like harmless stories.

Exterminating the Polish and Russian Jews was the necessary counterpart, the negative

Dopplegänger,

to Hitler’s and Himmler’s program to colonize the East, clearing the territory just as the Kaiser’s general Lothar von Trotha had cleared Namibia of the Herero. Hitler’s decision in the summer of 1941 to murder the Jews of the East as partisans under cover of Stalin’s partisan order answers a question that has confused Holocaust scholarship for many years: When did Hitler order the Final Solution? The answer appears to be: Progressively emboldened by military success and military challenges, he ordered direct killing (as opposed to death by privation) in two parts at two different times.

The first part, for the Jews of the occupied East (meaning Poland and the Soviet Union), he ordered in July 1941. His decision followed directly from Stalin’s partisan order and was a logical extension of the program formulated before Barbarossa to strip the occupied lands of food. “They deliberately and systematically planned to starve millions of Russians,” the United States assistant trial counsel charged at Nuremberg. The prosecutor called the economic policy Göring’s staff had formulated “a studied plan to murder millions of innocent people through starvation,” a “program of premeditated murder on a scale so vast as to stagger the human imagination.” The German document he cited to support his accusation acknowledged famine for “many tens of millions of people” who would “become redundant and will either die or have to emigrate to Siberia.” Destroying the Soviet population by starvation, writes the German historian Christian Gerlach, proved to be impractical, and the program “was replaced in the fall of 1941 by programs for eliminating groups of specific individuals, like the millions of Soviet war prisoners who were ‘incapable of work.’ ”The largest group to be eliminated was the Jews.

Two consecutive decisions to subject populations of Jews to direct killing, the first population the Eastern Jews, explains why, after the war, Höss remembered being told in the summer of 1941 that the Führer had ordered the Final Solution. Himmler had called him into his office in Berlin, a meeting that Breitman reliably dates during the period 13–15 July 1941, one of the few times that summer when Himmler was in the German capital. As Höss recalled the meeting:

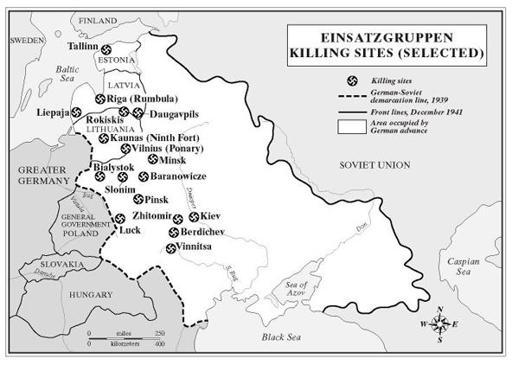

Contrary to [Himmler’s] usual custom, his adjutant was not in the room. The Reichsführer-SS greeted me with the following: “The Führer has ordered the Final Solution of the Jewish question. We, the SS, have to carry out this order. The existing extermination sites in the East [e.g, Ponary, the Ninth Fort] are not in a position to carry out these intended operations on a large scale. I have therefore chosen Auschwitz for this purpose.”

Himmler told Höss why he had chosen him rather than someone of higher rank—because (according to Höss) he thought Höss was the most competent person “to deal with such a difficult assignment”— and cautioned him to keep the assignment secret. Höss also remembered being told that a Sturmbannführer named Adolf Eichmann would soon visit him with details. This part of Höss’s recollection is almost certainly conflated with the second, later decision also to murder the Jews of

western

Europe, because Eichmann specifically recalled going directly from

his

first briefing on the Final Solution, by Heydrich, to Lublin to meet Globocnik, who took him to see a gassing installation at a death camp that did not exist before December 1941.

Höss wrote his confession in 1947. His memory of being assigned in the summer of 1941 to begin preparing to murder large numbers of (Polish) Jews at Auschwitz (up to that time a labor camp) is consistent with Himmler’s actions immediately before and after his visit to Lublin and Zamosc. As Christopher Browning points out, “if the historian wants to know when the Nazi leadership decided that the mass murder of Russian Jewry was no longer a future task but rather a goal to be achieved immediately, he must ascertain when the decision was taken to commit the necessary manpower.” Himmler took that decision in July 1941.

Just after the beginning of Barbarossa, on 27 June 1941, Himmler had assumed personal command of two brigades of Waffen-SS totaling some eleven thousand men serving behind the lines on the Russian front, explaining, “I need these units for other tasks.” The task force staff originally organized to supervise the Einsatzgruppen—the Einsatzstab — had been absorbed into Himmler’s command staff even before the beginning of Barbarossa, becoming the Kommandostab Reichsführer-SS, and the two brigades were now attached to this office. Other units— an SS cavalry brigade, a volunteer regiment and several brigades of mechanized Waffen-SS— were also attached to the Kommandostab, increasing the total force to thirty-six thousand. It answered only to Himmler, and Himmler answered only to Hitler. By the beginning of July 1941, then, Himmler had assembled a substantial private army.