Masters of Death (22 page)

Blobel testified at his postwar trial that he remembered hearing the “strict order”—meaning the Führerbefehl, the Führer’s Eastern extermination order—around the time of his birthday, 13 August 1941. Erwin Schulz of Einsatzkommando 5 confirmed the occasion, dating it around 10–12 August 1941:

After about two weeks’ stay in Berdichev the commando leaders were ordered to report to Zhitomir, where the staff of Dr. Rasch was quartered. Here Dr. Rasch informed us that Obergruppenführer Jeckeln had been there, and had reported that the Reichsführer-SS had ordered us to take strict measures against the Jews. It had been determined without doubt that the Russian side had ordered to have the SS members and Party members shot.

25

As such measures were being taken on the Russian side, they would also have to be taken on our side. All suspected Jews were, therefore, to be shot. Consideration was to be given only when they were indispensable as workers. Women and children were to be shot also in order not to have any avengers remain.

26

We were horrified, and raised objections, but they were met with a remark that an order which was given had to be obeyed.

Günther Herrmann, who commanded Sonderkommando 4b, had been reproached at the meeting for not carrying out enough executions; his deputy commander, Lothar Fendler, testified that Herrmann complained afterward of having “had the feeling that they judged the efficiency of a commando according to the numbers of persons the commando executed.” Blobel testified further that Rasch had quoted Jeckeln saying pointedly “that the measures against the Jewish population had to be sharper and that he disapproved of the manner in which they had been carried out until now because it was too mild.”To all these professional murderers, Jeckeln’s message was clear: shoot more Jews.

SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger, based in Kaunas, began shooting more Lithuanian Jews in mid-August. Besides directing the ongoing Daugavpils executions northward in Latvia, he sent his Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann “and eight to ten reliable men from the

Einsatzkommando . . .

in cooperation with Lithuanian partisans” to the northern Lithuanian town of Rokiskis to purge a temporary concentration camp set up there that confined more than three thousand Jewish men, women and children.

Jäger

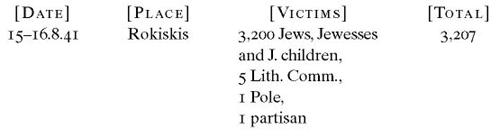

is the German word for hunter; in the notorious Jäger Report that the Einsatzkommando 3 commander filed with his superiors later in the year, he used the Rokiskis murders to brag about “the difficulties and the acutely stressful nature of the work: In Rokiskis 3,208 [

sic

] people had to be transported four and a half kilometers before they could be liquidated. In order to get this work done within twenty-four hours, over sixty of the eighty available Lithuanian partisans had to be detailed for cordon duty.” In the grisly running tally Jäger offered in his report, the Rokiskis

Aktion

is listed as follows:

Unlike the lawyers who headed most of the Einsatzgruppen commandos, Jäger saw no need to justify executions by pretending they were punishments for crimes or partisan activity; the Rokiskis tally, listing Communists and one lone partisan separately, and indeed the entire Jäger Report, verify that Jews were murdered simply for being Jews. The Jäger Report running tally reveals that Jäger’s men had been killing “Jewesses” in smaller numbers since early July 1941, but Rokiskis is the first entry that specifies Jewish children separately.

Two days later in Kaunas, where the Jewish community had recently been driven into a ghetto, Jäger’s killers would achieve a lethal entrapment. William Mishell recalls the deception:

A representative of the German administration . . . ordered the [Jewish] council to recruit five hundred professionals — doctors, lawyers, engineers, and other college graduates—for work on Monday, 18 August. He explained that the people had to be intelligent and conversant in Russian and German since the work consisted of sorting and straightening out the records in the city hall of Kovno, which were left in complete disarray by the retreating Russians. The work would be indoors and three meals would be provided. He assured the council that the treatment would be proper, in order to give the men an opportunity to do a decent job. Under the starvation conditions of the ghetto, the lure of three meals a day was not to be underestimated.

The news about this new job offer quickly circulated around the ghetto. The ghetto police informed as many of the Jewish intelligentsia as possible in the hope of helping people to an easier office job. . . .

The weeks passed but no news came from the workers. Daily the families beseeched the council, but nothing authoritative could be obtained. Meanwhile some Lithuanians came to the ghetto fence and told the people who lived there that all 534 Jews had been shot the same day, 18 August, at the Fourth Fort. . . . Almost the entire intelligentsia of Jewish Kovno had thus been liquidated in one mass execution.

Either Mishell’s number is an underestimate, or Jäger’s number is inflated: the Einsatzkommando 3 commander lists “711 Jewish intellectuals from ghetto” in his running tally for 18 August 1941, adding, “in reprisal for sabotage action”— a rare instance of justification, typically fraudulent. Jäger also lists “689 Jews, 402 Jewesses, 1 Pole (f[emale])” executed at the Fourth Fort on the same day.

Once begun, Jäger’s comprehensive mass murders quickly and sickeningly expand in scope. On 22 August 1941 he reports Latvian auxiliaries under German supervision emptying a psychiatric hospital: “Mentally sick: 269 men, 227 women, 48 children, [total killed] 544.” The hospital was located in Daugavpils; the patients were trucked to the small town of Aglona, thirty-five miles northwest, to be shot into killing pits. A September Einsatzgruppen report explains bizarrely that “ten males who could be regarded as partially cured were discharged by the governor of that institution, Dr. Borg, after steps for their sterilization had been taken,” the discharge and sterilization indicating that the hospital patients were not Jews. Almost half the children murdered at Aglona were normal: of the forty-eight, twenty happened to have been transferred to the hospital from a children’s home.

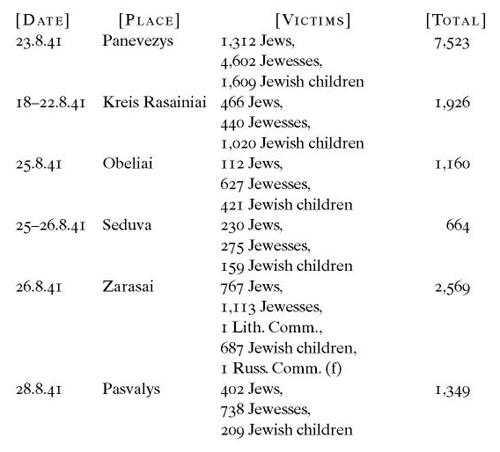

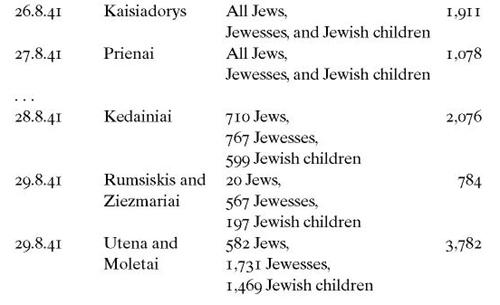

Jäger’s units worked relentlessly at mass murder for the rest of August:

Even this partial tally, omitting smaller massacres, records almost twenty-five thousand people brutally murdered in one region by one Einsatzkommando with the assistance of native auxiliaries in less than one month.

Near the end of August 1941 Jeckeln perpetrated the SS’s first five-figure massacre at Kamenets-Podolsky, an old fortress city anchored on limestone bluffs overlooking the Dniester River in the southwestern Ukraine.

Some thirty-five thousand Jews escaping Nazi persecution in Austria, Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia had found refuge in Hungary in the years before Barbarossa despite the fact that Hungary was Fascist and had been the first country in Europe to adopt anti-Semitic laws. Many of these escapees had been settled in refugee camps; all had been required to register with the National Central Alien Control Office. When Hungary joined Germany in attacking the Soviet Union, its forces advanced northeast beyond the Carpathian Mountains into the Ukraine and took military control of the extensive piedmont region southwest of the Dniester. Anti-Semites in the Alien Control Office then proposed to the Hungarian General Staff a plan “to expel from Carpatho-Ruthenia all persons of dubious citizenship [i.e., alien Jews] and to hand them over to the German authorities in Eastern Galicia.”

Admiral Nicholas Horthy, the man on a white horse who had overthrown the short-lived Soviet republic in Hungary in 1919 and installed a Fascist regime in its place, ruled the country as Regent. Horthy approved the expulsion plan. It was negotiated with the Gestapo. The Hungarian council of ministers issued a decree authorizing it on 12 July 1941. A secret directive to the Alien Control Office implementing it specified that its objective was the “deportation of the recently infiltrated Polish and Russian Jews in the largest possible numbers and as fast as possible.” They would be allowed to take with them three days’ food, personal items they could carry and the equivalent of about three dollars in Hungarian

pengös.

During late July and August 1941, Jews lacking Hungarian citizenship papers from the refugee camps, from Budapest and from small towns in the Carpathians were rounded up on short notice, often at night, crammed into freight cars, shipped northeast across the Carpathians to the border town of Korosmezo and turned over to the Germans, who transported them by train to Kolomiya in German-occupied Ukraine. From there the Germans marched them to temporary settlement in the area of Kamenets-Podolsky. By late August 1941 about sixteen thousand refugees had been expelled. The German military complained that it “could not cope with all these Jews,” claiming they menaced Wehrmacht lines of communication. The Hungarians refused to readmit the refugees they had expelled, and they continued sending more across. The problem found its way onto the agenda of a military conference that Jeckeln attended in Vinnitsa on 25 August 1941, where its solution entered the conference record: “Near Kamenets-Podolsky the Hungarians have pushed about 11,000 [

sic

] Jews over the border. In the negotiations up to the present, it has not been possible to arrive at any measure for the return of these Jews. The Higher SS and Police Leader [i.e., Jeckeln] hopes, however, to have completed the liquidation of these Jews by 1 September 1941.”

Historian Randolph Braham describes Jeckeln’s subsequent

Aktion:

The extermination of the Jews deported from Hungary was carried out during [27–28 August 1941]. According to an eyewitness account, the deportees were told that in view of a decision to clear Kamenets-Podolsky of Jews they would have to be relocated. They were surrounded by units of the SS, their Ukrainian hirelings and a Hungarian sappers’ platoon, and, together with the indigenous Jews of Kamenets-Podolsky, were compelled to march about ten miles to a series of craters created by bombings. There they were ordered to undress and brought into the crossfire of machine guns. Many of them were actually buried alive.

(Historian Richard Breitman found records of Jeckeln radio transmissions indicating that different units were involved: “His staff company did the shooting, and Police Battalion 320 cordoned off the area.”)

An Einsatzgruppen report on 11 September 1941 summarized the massacre: “In Kamenets-Podolsky 23,600 Jews were shot in three days by a commando of the Higher SS and Police Leader.” Of the 23,600 men, women and children murdered, Braham estimates, 14,000 to 16,000 had been refugees, the balance Ukrainian Jews from Kamenets-Podolsky.

Since the decision to expand the scope of Einsatzgruppen killing was only promulgated beginning in late July, the Hungarian authorities who decided to expel “alien” Jews from Hungary may not have known that they were sending the entire population to its death. Their intentions were hardly benevolent, but they appear to have stopped short of mass murder. When the Hungarian minister of the interior learned of the Kamenets-Podolsky massacre, at least, he ordered the deportations halted; seven trainloads of potential victims already on their way were recalled.