Masters of Death (24 page)

NINE

“All Jews, of All Ages”

The Wehrmacht turned over the Ostland—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and western Byelorussia—to German civil administration at the end of July 1941. The Reichskommissar for the Ostland, Heinrich Lohse, was a fanatical Nazi, but his first priority was restoring productivity to the regions he would now administer. He modeled his program for the urban Jews of the Ostland on the Nazi program in Poland: ghettos and forced labor rather than immediate extermination.

Stahlecker, the commander of Einsatzgruppe A, took issue with Lohse’s program in a letter to Berlin dated 6 August 1941. Lohse, Stahlecker wrote, had failed to “examine the unprecedented possibility of a radical treatment of the Jewish question in the Eastern regions.” He “apparently does not foresee the resettlement of the Jews . . . as an immediate measure but rather sees it as a slower, later development. This will have the consequence that the Jews in the foreseeable future will remain in their present residences. . . . In view of the small number of German security and order forces, the Jews would continue their parasitical existence there and continue to play a disruptive role.” In the dark mirror of Nazi paranoia, anti-Semitic hatred reflected back as Jewish malevolence; postponing extermination appeared to be a correspondingly extreme risk. But for the time being, Lohse’s guidelines prevailed.

Which is not to say the Ostland Jews were protected. Lohse ordered the rural districts under his authority purged of Jews. That was the work the Arajs commando took up in Latvia. Jews in larger cities were to be marked, restricted and moved into ghettos established in neighborhoods where large numbers of Jews already lived, thus displacing the smallest possible number of Gentiles.

Ghettoization therefore loomed for the Jews of Vilnius at the beginning of September 1941. The Vilnius district commissioner, Hans Hingst, and Vilnius’s Lithuanian mayor designated for the ghetto the old Jewish quarter near the center of the city. The quarter was already fully occupied. To make space available, Hingst staged what the Jews of Vilnius came to call the Great Provocation.

On the afternoon of 31 August 1941, two Lithuanian men carrying concealed weapons entered an apartment house in the Jewish quarter that overlooked a square where German soldiers were waiting to enter a cinema. The two men fired shots inside the house and ran out shouting that Jews had fired on the square. The soldiers followed the men back into the house, dragged out two Jewish men, beat them and shot them dead.

That night Lithuanian auxiliaries arrested Jews living in the area around the square and on three nearby streets of the Jewish quarter and crowded them into the cells and courtyard of Lukiszki Prison, north near the river.

The next day Hingst had notices posted throughout the Jewish quarter claiming “shots were directed from ambush at German soldiers in Vilnius.” The notices ordered all Jews except those who had valid work passes to remain confined to their homes from three o’clock that afternoon until ten o’clock the following morning. That night five more streets in the Jewish quarter were cleared of Jews.

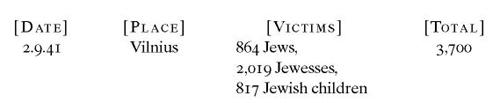

From Lukiszki Prison these 3,700 victims went off in batches to Ponary. Men were made to march to the killing site, three miles south of the prison; women and children rode in trucks. The Jäger Report includes the Great Provocation in its callous bookkeeping:

Exceptionally, Jäger cites the supposed provocation as the reason for the Vilnius “special action”: “Because German soldiers [were] shot at by Jews.”

Moving into the Vilnius ghetto was ordered for 6 September 1941, a Saturday. Making Jews work on the Sabbath was a Nazi joke, a deliberate expression of contempt. Yitzhak Rudashevski, a fourteen-year-old schoolboy who kept a diary of the Vilnius ghetto, felt the anxiety around him:

The situation has become more and more strained. The Jews in our courtyard are in despair. They are transferring things to their Christian neighbors. The sad days begin of binding packages, of sleepless nights full of restless expectation about the coming day. It is the night between the fifth and the sixth of September, a beautiful, sleepless September night, a sleepless, desperate night, people like shadows. People sit in helpless, painful expectation with their bundles. Tomorrow we shall be led to the ghetto.

But Gebietskommissar Hingst soon realized that even with the Great Provocation he had not reduced the Jews of Vilnius sufficiently to crowd them into the two ghetto spaces, one larger and one smaller, that his subordinates had delimited. “The Lithuanians drive us on, do not let us rest,” Rudashevski says of moving among tens of thousands of people the next day. “I think of nothing: not what I am losing, not what I have just lost, not what is in store for me. I do not see the streets before me, the people passing by. I only feel that I am terribly weary, I feel that an insult, a hurt is burning inside me. Here is the ghetto gate. I feel that I have been robbed, my freedom is being robbed from me, my home, and the familiar Vilnius streets I love so much. I have been cut off from all that is dear and precious to me.” Rudashevski made it into the ghetto, but others were diverted to the prison. A woman remembered that cruel diversion:

The march to Lukiszki was terrible. Thousands of Jews were rushed along like sheep, and beaten with rubber truncheons in the darkness of night.... The elderly stumbled and fell, and died; children lost their mothers, and parents lost their children. Everyone was wailing, and their cries filled the dark. We were taken to prison. Hundreds of Germans and Lithuanians opened the gate for us and, in doing so, beat the children, fathers and mothers. Many of them jeered at us and promised us death.

By the end of the action on Sunday evening, about thirty thousand people had been locked into Vilnius Ghetto No. 1, ten thousand into Ghetto No. 2 and six thousand into Lukiszki prison.

Lohse’s program partly determined the fate of the people crowded into the prison. SS men confiscated money and valuables, filling the buckets they carried to the task. They made lists of the names of doctors, engineers and skilled workers. On 8 September 1941 they called out the names on their lists. Instead of sending them to Ponary to be murdered, as Jäger had done in Kaunas, they ordered them into Ghetto No. 1.

Those left behind at Lukiszki — twice as many women and children as men—were destined for Ponary. A schoolteacher, Sima Katz, the mother of three children, survived to tell the story of her encounter with what Rudashevski would call “the great grave”:

At Lukiszki we were kept outside for two days and then put into cells. We learned that the previous inmates had been sent to Ponary, but no one thought that all of them had been killed.

We remained there until Thursday [11 September 1941]. At two a.m. the prison square was suddenly illuminated with floodlights. We were put aboard trucks, fifty to sixty women in a truck. In each vehicle there were armed Lithuanian sentries. The trucks headed for Ponary.

We came to an area of wooded hillocks and were dumped among them. Still, the mind would not keep pace with reality. We were arranged in rows of ten and prodded toward some spot, from which came the sound of shooting. The Lithuanians then went back for more batches of people.

Suddenly the truth hit us like an electric shock. The women broke out in piteous pleas to the sentries, offering them rings and watches. Some fell to the ground and kissed the sentries’ boots, others tore their hair and clothes — to no avail. The Lithuanians pushed one group after another to the site of the slaughter. By noon, when it became clear that there was no escaping this fate, the women fell into a kind of stupor, without any pleading or resistance. When their turn came, they went hopelessly to their death.

Suddenly we saw a group of men. At their head was an aged rabbi, wrapped in his prayer shawl; passing us he called out “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people.” We were seized with trembling. The women broke into moans, and even the Lithuanians took notice. One of the guards ran up and hit the rabbi with the butt of his rifle. My daughters and I were on the ground. Other women did not wait to be led away but broke from the rows and went on. The rows were broken. The women sat down and waited for a miracle to halt the massacre. I had one thought in mind: to be among the last.

Our turn came at five-thirty. The guards rounded up the remaining women. I felt my older daughter’s hand in my own. . . . When I came to, I felt myself crushed by many bodies. Feet were treading on me, and the acrid smell of some chemical filled the air. I opened my eyes; a young man was sprinkling us with quicklime. I was lying in a huge common grave. I held my breath and strained my ears. Moans and sounds of dying people, and from above came the amused laughter of the Lithuanians. I wished myself dead so that I would not have to hear the sounds. Nothing mattered. It did not dawn on me that I was unhurt.

A child was whimpering a short distance away. Nothing came from above. The Lithuanians were gone. The whimper aroused me from my stupor. I crawled toward the sound. I found a three-year-old girl, unharmed. I knew that if I survived, it would be thanks to her.

I waited for darkness to fall; then, holding the child in my arms, I wriggled up to the surface and headed for the forest. Not far in the interior, I came upon five other women who had managed to survive. Our clothes were smeared with blood and burnt from the quicklime. Some of us had nothing but our underclothes on our skin.

We hid for two days in the forest. A peasant came by and was frightened out of his senses. He let out a weird shriek and fled. But he was not decent enough to come back and help us. He was sure that we were ghosts from another world.

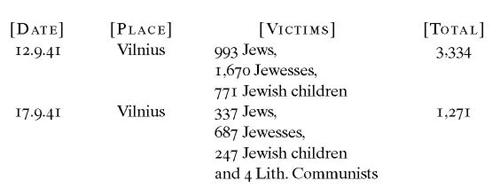

The Jäger Report lists the massacre Sima Katz survived and another one five days later:

In Minsk in September 1941 Nebe, Bach-Zelewski and the commander of Rear Army Group Center organized a course of instruction in antipartisan warfare. The course was based on the premise that “wherever there is a Jew there is a partisan, and wherever there is a partisan there is a Jew.” For training, participants rounded up and shot all the Jews in a Byelorussian village.

A woman in a small town near Minsk saw a young German soldier walking down the street with a year-old baby impaled on his bayonet. “The baby was still crying weakly,” she would remember. “And the German was singing. He was so engrossed in what he was doing that he did not notice me.”

The Final Solution in the area of the western Ukraine that included Zhitomir and Vinnitsa would not begin with ghettos. Himmler intended to establish his field headquarters in Zhitomir once the area was secure, and a forward Hitler bunker, Werwolf, was to be built north of Vinnitsa. So that the Führer might sleep peacefully, the territory for forty miles in every direction was scheduled to be made

Judenfrei.

Connected massacres under Jeckeln’s authority winnowed the region throughout September 1941.

The massacres began in Berdichev, sixteen miles south of Zhitomir on the road to Vinnitsa, an industrial town of sixty thousand where half the population was Jewish. Jews in Berdichev worked at the Ilyich Leather Curing Factory, the Progress Machine Tool Factory, the Berdichev Sugar Refinery. In smaller shops and factories they made shoes, hats, cardboard and metal products and soft slippers called

chuvyaki

known throughout the Russian-speaking world. “Thousands of Berdichev Jews,” writes the Russian war correspondent Vasily Grossman, “worked as stone masons, stove builders, carpenters, jewelers, watch repairmen, opticians, bakers, barbers, porters at the railroad station, glaziers, electricians, locksmiths, plumbers, loaders. . . . [There were] dozens of senior, experienced doctors — internists, surgeons, pediatricians, obstetricians, dentists. There were bacteriologists, chemists, druggists, engineers, technicians, bookkeepers, teachers in the numerous technical schools and high schools. There were teachers of foreign languages, teachers of music, women who worked in the nurseries, kindergartens, and playgrounds.”