Masters of Death (26 page)

Once Zhitomir was secured, Blobel had suggested to the military administration that Zhitomir Jews should be confined to a restricted area. “This resulted in a quieter atmosphere,” the Sonderkommando 4a commander wrote Berlin at the end of September. “. . . Simultaneously, a number of previously persistent rumors died down and it seemed as well as if Communist propaganda lost much ground.” Blobel claimed that restriction without a ghetto was insufficient, however, and “the old troubles soon started again.” These troubles, a familiar Einsatzgruppen litany, included “complaints . . . about the insolent attitude of Jews in their workplaces,” propaganda among the Ukrainians that the Red Army would soon return traced to “the Jewish district,” the local militia “shot at from ambush at night and also by day” and Jews selling their belongings to fund escaping to the western Ukraine. These things happened, Blobel went on, but only rarely could the Jews responsible for them be arrested; without ghetto confinement they had “sufficient opportunities to evade arrest.”

Heinrich Himmler, the son of a Bavarian schoolmaster, took command of the SS— Schutzstaffel, the Nazi Party’s police and security service — at the age of twenty-nine in 1929. He dreamed of clearing Poland and Russia to make room for colonies of German soldier-farmers.

Hermann Göring, Himmler and Adolf Hitler collaborated to disarm the SA— Sturmabteilung, Hitler’s first paramilitary organization— and murder its leadership in June 1934. The purge consolidated their power.

With the invasion of eastern Poland and the U.S.S.R. on 21 June 1941, Himmler unleashed the 3,000 men of his deadly Einsatzgruppen and tens of thousands of Order Police to murder Communists and Jews.

In Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania, one of the first towns occupied by the Nazis, the SS opened the jails and encouraged local criminals and victims of Soviet repression to publicly murder Jews. The “Death-dealer of Kovno” posed for a portrait among the victims he had beaten to death with a crowbar.

Hoping at first to make their killing appear spontaneous, the Einsatzgruppen organized local auxiliaries. Here, Lithuanian paramilitary herd Jewish women toward one of the old czarist forts around Kaunas that served as prisons and killing sites.

At the Seventh Fort outside Kaunas the Lithuanian auxiliaries confined Jewish men without food or water for days before killing them with rifle and machine-gun fire.

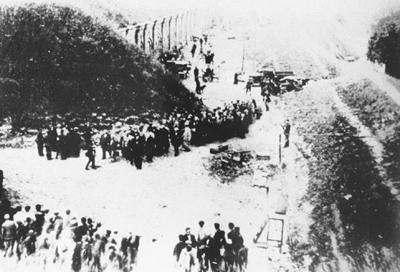

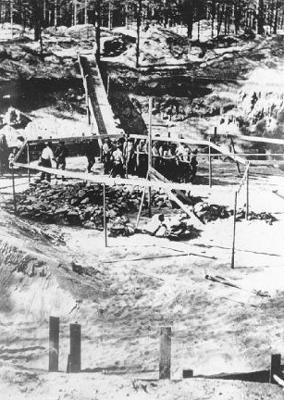

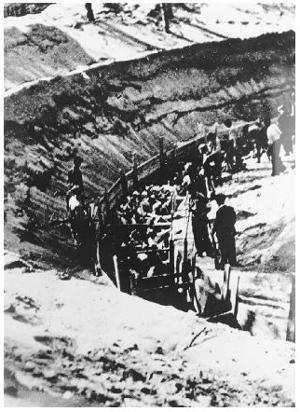

Ponary, an unfinished Soviet fuel storage site outside Vilnius, Lithuania, became one of the most terrible mass graves of the war. From a holding area (left), men with their heads

covered were lined up and driven across a walkway to another pit, where they were shot to death.

The Einsatzgruppen followed the Wehrmacht as it swept eastward across Poland and the western Soviet Union. They soon gave up trying to incite the local population to murder and began mass killing themselves. To condition their forces to killing, they limited the victims at first primarily to men.

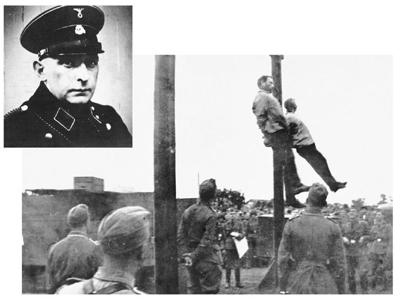

Paul Blobel, an alchoholic former architect, commanded Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C. He learned to organize highly efficient massacres.

After publicly hanging a Jewish Soviet judge, Wolf Kieper, and his assistant in the western Ukrainian town of Zhitomir in August 1941 (above), Blobel organized a roundup of terrified local Jews with German soldiers looking on. The victims were driven to a killing pit on the edge of town and shot to death.