Masters of Death (41 page)

Medale survived to serve as a witness at Arajs’s trial.

After the shooting stopped and Russian-speaking prisoners began shoveling earth over the dead, Michelson could hear the perpetrators, Latvian and German, from under her saving mountain of shoes:

Suddenly I heard Latvian being spoken very close by: “Let’s have a smoke.”

“A fine performance.”

“It was very efficiently organized.”

“They have experience.”

“Just leave it to the Germans; they are good at it.”

“I hope we get our cut of the booty.” Pause— “The Germans have first choice.”

“There is enough for everybody.”

“I’m tired. I’m going home.”

“Me too.”

“Goodbye.”

“Goodbye.”

After a pause I heard German spoken: “Was suchst du dort?” (“What are you looking for there?”)

“Ein Paar Strümpfe für meine Frau.” (“A pair of stockings for my wife.”)

Quiet for a while. Then, from the direction of the trench a child’s cry: “Mama! Mama! Mamaaa!”

A few shots. Quiet. Killed. Then in German this smug assertion: “From our kettle nobody escapes alive.”

The bridge-inspection officer whose report had reached Hitler wrote his wife a month later that German Jews had been moved into the area—into a camp and into the emptied ghetto. He could hear Swabian accents in the camp, he wrote, and Berlin accents in the ghetto. “How long will it be,” he asked his wife rhetorically, “until these Jews, too, are ‘resettled’ to the pine forest, where I recently saw mounds of earth heaped up over five large pits, sharply sagging in the middle, and despite the cold a sickly, sweet odor lingered in the air?”

“After the killings,” Ezergailis notes, “Jeckeln had told [his aide Paul] Degenhart that 22,000 rounds of ammunition had been used at Rumbula. Noting that on the two days more than 1,000 people were killed within the ghetto and on the road to Rumbula, the number adds up to just below 24,000.” Adding in the trainload of victims from Berlin brings the total to twenty-five thousand.

“Although the bodies were picked up quickly,” Ezergailis concludes his lamentation, “the ghetto remained in a shambles, and for days thereafter it bore the evidence of a pogrom. Broken suitcases, furniture, toys and baby carriages were all over the streets and yards. The houses were desolate, blood was splashed on the walls and in the stairwells. Days after the

Aktion,

frozen rivulets of blood were on the sidewalks and gutters. Even two months later, arriving German Jews found corpses in cellars and attics.”

Jeckeln must have satisfied the Reichsführer-SS that he had not deliberately disobeyed. For his evil work liquidating the Riga ghetto he received a further promotion, to Leader of the SS Upper Section, Ostland, on 11 December 1941.

FOURTEEN

Nerves

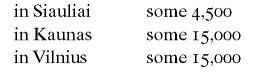

Karl Jäger’s notorious report on the murderous work of Einsatzkommando 3, issued from Kaunas on 1 December 1941, cumulates to a total of 137,346 deaths in five months in the area assigned to one Einsatzkommando alone. “I can state today,” Jäger writes in summary, “that the goal of solving the Jewish problem in Lithuania has been reached by Einsatzkommando 3. There are no Jews in Lithuania anymore except the work Jews and their families, which total “I intended to kill off these work Jews and their families too,” Jäger goes on with malicious bravado, “but met with the strongest protest from the civil administration (

Reichskommissar

) and the Wehrmacht, which culminated in a prohibition: these Jews and their families may not be shot dead!”

In Kaunas in the final days before he issued his report, on 25 and 29 November 1941, Jäger had overseen massacres of Reich Jews shipped east from Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt, Vienna and Breslau, a total for the two days of 1,869 men, 2,716 women and 327 children, all shot into the killing pits of the Ninth Fort. Since Reich Jews shipped to Lodz had not been immediately killed, and since Himmler vehemently protested Jeckeln’s unauthorized killing of the Berlin Jews shipped to Riga, these prompt Kaunas massacres are anomalous. Historian Christian Gerlach notes that the Ostland section chief in the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Territories in the East met with Jäger on 22 November 1941 “and expressed his satisfaction with the executions of Lithuanian Jews,” which to Gerlach indicates that the Ministry for the East “was in agreement with the plan to execute the German Jews who were expected to arrive in Kaunas.” But no documents have yet emerged that reveal who ordered these anomalous slaughters before Hitler authorized the direct killing of Western Jews.

In his swaggering summary Jäger assesses the relative difficulties of various

Aktionen,

commenting that “the

Aktionen

in Kaunas itself, where a sufficient number of trained partisans [i.e., Lithuanian auxiliaries] was available, can best be described as parade shooting, especially if compared with

Aktionen

in the country, where the greatest difficulties had to be overcome again and again.” Like Jeckeln, Jäger had required all his subordinates to participate in the massacres: “All commanders and men of my commando in Kaunas took part in the large-scale

Aktionen

in Kaunas most actively.” Only one official, Jäger adds, was released from participating “because of ill health.”

In a follow-up telegram in early February 1942 Jäger increased his total of Jews murdered by 75, to 136,421, added the 1,851 non-Jews his subordinates had executed and gave a breakdown of this total of 138,272 by age and gender: 48,252 men, 55,556 women and 34,464 children.

Stahlecker, in a second long report that covered the period up to 31 January 1942, similarly concluded that the work of Einsatzgruppe A in the Baltic and Byelorussian Ostland was largely finished, a point Stahlecker gruesomely dramatized with a map studded with coffins sized proportionally to the number of Jewish victims. Subsuming Jäger’s tallies, the Einsatzgruppe commander gave a combined total for Latvia and Lithuania of 229,052 Jewish men, women and children liquidated, a veritable city of the dead. There were still about 128,000 Jews remaining in Byelorussia, he noted, and killing them was “fraught with certain difficulties,” including the need for Jewish labor, frozen ground and shortages of fuel and transportation. These difficulties were not insurmountable; they only meant that he would need two more months to finish the job.

Frozen ground was limiting more than Einsatzgruppen murders; Russian winter had stalled the Wehrmacht just as it had stalled Napoleon in 1812. Wehrmacht officer Siegfried Knappe found it brutally unforgettable:

By December [1941], we were no more than twenty-five kilometers [16 miles] from Moscow, but the temperature was paralyzing. Heavy snow fell on December 1, and the pitiless cold became unbearable. . . .

As we approached the outermost suburbs of Moscow a paralyzing blast of cold hit us, and the temperature dropped far below zero and stayed there. Our trucks and vehicles would not start, and our horses started to die from the cold in large numbers for the first time; they would just die in the bitter cold darkness of the night, and we would find them dead the next morning. The Russians knew how to cope with this weather, but we did not; their vehicles were built and conditioned for this kind of weather, but ours were not. We all now numbly wrapped ourselves in our blankets. Everyone felt brutalized and defeated by the cold. The sun would rise late in the morning, as harsh now in the winter winds as in the heat of August, and not one fresh footprint would be visible for as far as the human eye could see. Frostbite was taking a very heavy toll now as more and more men were sent back to the field hospitals with frozen fingers and toes. Many infantry companies were down to platoon size. On December 5, the temperature plummeted to [−22° F.]. It was almost impossible for the human body to function in such numbing cold.

But Himmler’s murderous forces were nothing if not dogged. The last major massacre in Liepaja, on the western Baltic coast of Latvia, took advantage of the friability of the deep sand dunes back from the beach at Skede, ten miles north of the city. Prisoners dug a V-shaped trench twenty feet deep in the sand and notched a ledge four feet down the ditch’s seaward wall, on which victims were forced to stand facing the ocean to be shot from behind. Mass killings at Skede on orders from Riga during three days in mid-December 1941 destroyed about half the Liepaja Jewish population, some three thousand men, women and children. It was not as cold on the beach as Moscow’s deep freeze, but a bitter wind was biting and the Liepaja victims were required to remove all their clothes and stand naked or nearly so. Rather than

Sardinenpackung,

the Latvians and Germans who did the killing reverted to the military system of two executioners firing simultaneously at each victim. But mothers with infants were told to hold their babies over their heads; one man then shot the mother while the other shot the child. “For the corpses that did not fall into the ditch” on their own, Ezergailis notes, “there was a kicker who rolled them in.” A German SD man working down in the ditch administered

Genickschüssen

to the wounded.

At Vinnitsa, in the Ukraine, where Wehrmacht engineers were building the forward Hitler bunker, Werwolf, an area forty miles around was declared

Judenfrei

in December 1941 after an October Revolution massacre of 2,580 Vinnitsa Jews. In fact, Jewish slave laborers continued to live and work in the Vinnitsa area. On 5 January 1942 the SS published an announcement in the

Vinnitsa News

ordering Jews to assemble for resettlement with luggage and a three-day supply of food. They complied, but conditions were such that the SS had to send them home; as the officer responsible for the Hitler bunker subsequently informed Berlin, the ground was frozen and it had been impossible to dig pits. Not to be thwarted in reducing the supposed risk to Hitler’s security in the neighborhood of Werwolf (which he would not occupy until July 1942), the SS seized 227 Jews who lived in the village nearest the bunker, lined them up against the wall of the local NKVD prison and killed and simultaneously buried them by dynamiting the wall.

By the end of 1941 many of the men of the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police and SD and their native auxiliaries had developed fully malefic violent identities. For some that meant taking pleasure in killing; for others it meant killing when ordered to do so and drinking afterward to forget.

An SS-Scharführer

44

named Ribe, for example, oversaw the Minsk ghetto. Ghetto resident Hersh Smolar remembers the Scharführer’s enthusiasm for viciousness:

[Ribe] was even more sadistic than his predecessors. Jews who had escaped from Slutsk and settled in the Minsk ghetto recognized him as the murderer who had been in charge of liquidating the Slutsk ghetto. People called him “the Devil with the White Eyes.” . . . Ribe never let any Jew he encountered go unscathed, regardless of age or sex. He would look at his victim with his big bulging eyes, his lips would form a smile, he would carefully aim his pistol—and never miss. It was Ribe who organized the “beauty contest” of young Jewish women, selected twelve of the youngest and prettiest, and ordered them to parade through the ghetto until they reached the Jewish cemetery. Here he forced them to undress and then shot them one by one. The last woman to be killed was Lena Neu. He took her brassiere from her and said smugly, “This will be my souvenir of the pretty Jewess.”

Ribe was the SS man as beast, a familiar and all-too-common type. Not all the Third Reich’s killers were so complacently socialized to violence, however. The discomfort that some of them felt certainly does not qualify as mitigation: crimes are judged by acts, not by facility. But the evidence that perpetrators exhibited a range of responses, often conflicted and even traumatic, supports Lonnie Athens’s model of violent socialization and disqualifies ideology alone as the enabling mechanism for violence.

SS-Obersturmführer Karl Kretschmer of Sonderkommando 4a responded to his murderous duties with ambivalence even though he was committed to the Third Reich’s anti-Semitic ideology and accepted the standard rationalizations of the Final Solution that Hitler and Himmler handed down. Kretschmer joined Sonderkommando 4a later in the war, after Blobel had been relieved and replaced by a physician, Erwin Weinmann, in January 1942, who in turn had been replaced by a former schoolteacher, Eugen Steimle, in August 1942. By then Sonderkommando 4a was working north of Stalingrad, far to the east of Kiev, but its work was the same as it had been since the beginning of Barbarossa: murdering Jews.

“The sight of the dead (including women and children) is not very cheering,” Kretschmer wrote his wife soon after he arrived behind the front. “But we are fighting this war for the survival or non-survival of our people. . . . As the war is in our opinion a Jewish war, the Jews are the first to feel it. Here in Russia, wherever the German soldier is, no Jew remains. You can imagine that at first I needed some time to come to grips with this.” Kretschmer counted himself lucky to be able to barter for food, a consequence of what he called “our hard work.” He and his men could also choose among clothing. “We can get everything here,” he told his wife. “The clothes belonged to people who are no longer alive today.” He could not ship her a “Persian rug” because “the Jewish dealers are no longer alive,” but he sent her canned butter, sardines, meat and tea.