Metallica: This Monster Lives (23 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

I said that I was indeed interested. The devastating last few days had reminded me that during my dark days after

Blair Witch 2

, I had a longing to make a deeply spiritual film. I told her that I had never really conceived this project in any detail, but I imagined something like

Koyaanisqatsi

and

Powaqqatsi

, Godfrey Reggio’s mesmerizing non-narrative films that make you see the modern world in an entirely new way. She told me that I was a gift, that the universe was aligning to create an opportunity for us to make a Kabbalah film. I was a little embarrassed by what she said, but also excited and, frankly, a little scared. I had spent months listening to Phil talk about the universe speaking, and now someone else was telling me that it was speaking directly to me. It was an intoxicating rush of spirituality, which actually made me a feel a little better about this terrible week.

I returned to New York, determined to learn more about Kabbalah and explore the possibility of collaborating with this woman on her film. She and I spoke a few times, but I ultimately decided the project was not for me. She wanted to make a very literal, straightforward film—interviews with people active in the movement, footage of the classes, etc.—but I felt that was a very limiting concept, and that a more poetic, metaphoric style would better convey the teachings of Kabbalah. (I was still thinking of Reggio’s films.) Thinking so much about this project and how much I wanted to make a spiritual film made me wonder what the hell our Metallica film was about. A few weeks after 9/11, I was in the shower (where I come up with many of my best ideas), and it occurred to me in a flash I didn’t need to search elsewhere for a spiritual film—I was right in the middle of making one, assuming we could nudge the film in the direction we wanted. One tenet of Kabbalah is that the ego is a potentially destructive force—an idea that James and Lars were struggling with; to some extent, so were Bruce and I. Our Metallica film was shaping up to be an exploration of human growth and creative potential. The subjects of the film were among the biggest stars in the music world, and their fans, many of whom felt persistently disaffected, could really benefit from this message.

One thing I love about

Some Kind of Monster

, that makes me proud to have helped bring it into the world, is that we managed to preserve the spirituality at its core. It has to do with the mystery of the universe speaking and the ways we grow as our lives intertwine with those around us. If Jason Newsted’s departure hadn’t triggered a moral crisis within Metallica, we wouldn’t have

had a film. If James Hetfield hadn’t reached rock bottom, Metallica quite possibly wouldn’t have come out of it all with a great album—or any album at all. If 9/11 hadn’t happened, I would bet that Dave Mustaine would have spent the rest of his life fantasizing about things he’d like to say to Lars Ulrich, rather than actually getting the chance. And, of course, if I’d decided to catch a plane leaving New York in the early morning of September 11, instead of late at night on September 10, I might not be here at all.

Blair Witch 2

, 9/11, the Kabbalah film project—they all played a role in helping me realize what

Monster

was about for me. I always thought that when I finally got around to making a spiritual film, it would be a modest undertaking with a limited audience. By documenting a spiritual quest through the lens of pop culture,

Some Kind of Monster

will reach a large number of people, for which I feel very fortunate.

LARS:

There was an incredible rivalry or competition between you and James. At the time, we couldn’t think about it and analyze it like we can now, but in retrospect it brought out a lot of great energy between you two, but also … I remember standing on the sidelines watching you two guys. One minute you’d hug and embrace, and the next minute you’d be close to fucking fighting each other. It was quite some energy.

DAVE:

When James and I picked up guitars and started playing in unison, the world changed. If you weren’t there, you don’t know. It was kind of like being Jonas Salk and discovering the cure for polio. You just knew you were onto something. And I’ve lived the last twenty years of my life, you know, cherishing that moment, just knowing, like, Jesus Christ, I learned how to split the fucking atom!

THE UNFORGIVEN

I think the session with Lars and Dave Mustaine is one of the film’s most powerful scenes. I also think (and comments I’ve heard from people who’ve seen

Monster

back me up) that Dave comes off very well: intelligent, poised, and articulate. He seems very unlike his reputation as an arrogant jerk. Dave didn’t necessarily see if that way, however, and tried to convince us not to use any footage of him.

In the summer of 2003, nearly two years after Lars’s encounter with Dave, we were deep into editing

Some Kind of Monster.

We decided to cut in clips from Megadeth’s music videos and some archival

MTV News

footage about the band. We really wanted

Monster

to be a film for everyone, not just Metallica fans. Much as we did with the “Temptation” montage, we figured a similar archival sequence about Megadeth would bring the uninitiated up to speed.

I contacted Mustaine’s two managers to make the request. Dave flipped out when he heard we were using the footage of him in the therapy session with Lars and Phil. He denied our request for archival material (MTV’s rules stipulate that the artist involved must approve of any requests for footage of that artist), and his people began pressuring us to remove any footage of Dave from our film. But I was so convinced that he would like the footage if he saw it (also, I really wanted the archival material) that I broke our long-standing rule of not showing works in progress to people we’ve filmed. I sent him the scene with him and Lars, emphasizing that I was doing so as a courtesy, not for his legal approval. Dave had signed our release form; several times during filming he’d asked us to shut off our cameras, suggesting his acceptance and awareness of the camera being on. I told his managers that I thought the scene rehabilitated Dave’s image. One manager agreed with me, but the other said that he thought Dave’s fans didn’t want to hear him admit that he’s “number two” and that being kicked out of Metallica still haunts him.

I told them that I had no doubt that we had the legal right to use the scene (I offered to send them the footage of Dave asking us to turn off the camera) but that I don’t personally like it when someone in our films regrets their participation. I suggested that maybe Dave needed to see the scene in the context of the film. I wasn’t allowed to send him a tape, but I offered to fly to Arizona to give him a private screening. Dave declined and reiterated, through his managers, that he wanted the scene removed. The managers appealed to my “sense of fairness and humanity.”

I pulled out my trump card. I said that I didn’t own

Some Kind of Monster

—Metallica did, and I’d be happy to let the band know Dave was unhappy with the scene. If they chose to honor Dave’s wishes, the scene would hit the cutting-room floor. “Maybe you should call Metallica’s manager, Cliff Burnstein,” I suggested. They laughed, as if to say, “Yeah, right.” Then one of them made some joke about sending a Mafia type to break my legs. I reiterated that it was Q Prime’s and Metallica’s call—not mine. Fortunately, Q Prime and Metallica didn’t want the scene excised, and I wasn’t about to disagree.

Courtesy of Joe Berlinger

CHAPTER 13

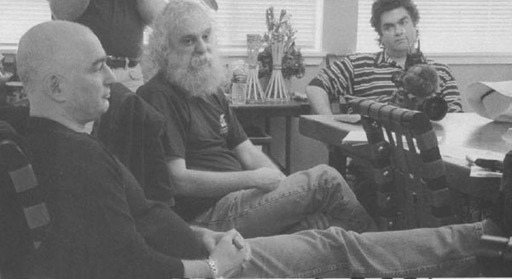

SEEK AND DEPLOY

We presented a conundrum to Q Prime’s Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein: would the things we were filming be harmful to the band’s image and finances? (Courtesy of Niclas Swanlund)

My encounter with the Kabbalah woman made me realize that I was making the spiritual film I’d always want to make.

The problem was, Bruce and I hadn’t really started

making

the movie—we’d just been shooting it. Even though my confidence lagged the longer James stayed away, we knew in our hearts there was a movie here that could transcend its original promotional intent. Finding myself back in New York, a city struggling to deal with the open wound of 9/11, it seemed like a good time to put Metallica’s money where our mouths were. It was time to begin cobbling together

Some Kind of Monster.

There’s no doubt that digital video has transformed the documentary world by freeing filmmakers to shoot the huge amount of footage verité documentaries demand. The downside is that video can be

too

easy to shoot. Because of the cost constraints of film, as well as the many technical problems that can result when shooting film, it’s important to screen material almost daily to see what you’ve got. With video, there are fewer variables that can negatively affect your footage, and it costs less, so you can shoot and shoot and shoot and ask questions much later. It’s easy to get lazy about watching your material. The next thing you know, you’re swamped in footage with little perspective about what you have.

In the months since we’d begun filming Metallica, we had made some effort to keep track of what we had. We would screen dailies from time to time to

take stock of our footage, but there’s a big difference between spot-checking dailies and really watching stuff with an eye toward editing it into something coherent. Bruce and I would often talk about our grand plans for the film, but we were relying too much on our memories of what we’d shot without an objective analysis of what we had. We were swimming in Metallica footage. Before we started to drown, we figured we should take stock of what we now had.

We don’t normally start editing while we’re still shooting. This is often a consequence of the logistics of documentary filmmaking; we’re usually too busy trying to stay on top of filming to think about anything else. Also, editing is an expensive process, so we don’t like to start it until we’re ready to focus on it completely But we were now in an odd situation. Without James, we found ourselves in a sort of hurry-up-and-wait situation: although we continued to film, we were in a holding pattern. I suggested to Q Prime that we start editing for two reasons. First, I wanted to see if what we had was as good as what we thought we had. I also wanted to keep this project alive in the minds of Metallica’s managers and Metallica themselves as they sank further into despair.

We had not yet begun to lobby for making this a feature film, but we did mention that we thought there was a strong television show here, hoping to nudge plans away from the infomercial idea. We felt the material was good enough for a network to buy it for a broadcast rather than Metallica and Elektra buying commercial time, which had been the plan all along. As an introduction to the footage, the Q Prime guys asked us to cut a trailer, so that they could get a sense of what we’d been doing. At this point, we already had a formidable four hundred hours of footage. In November, we hired David Zieff, an editor we’d worked with before, to begin to make sense of it. This was the first time Bruce and I had an editor work on our material without one of us in the room for directorial guidance. We left David to his devices and concentrated on filming. It was highly unusual to dump so much material on an editor with no instructions, but we were curious to see what a talented editor who was a complete outsider to the process would make of this material. David began by putting together “wide selects.” He would take a three-hour therapy session, for instance, and turn it into a ninety-minute reel of the best moments, which I would watch religiously.

The first clues that this film would not exactly edit itself—that it would in fact be as much of a slog as the actual filming—were the dejected phone calls we started getting from David while we were in San Francisco. He was really struggling. If there was a film here, he didn’t see it. He thought the therapy sessions were tedious and the jamming scenes maddeningly diffuse. He hated any scenes with Lars, whom he thought just came off as an ass. Barricaded in an editing room in New York, David felt we’d abandoned him with a quixotic task. “I don’t think I realized how vast it was going to be,” he says, looking back at that time. “I’m sitting there, screening hour after hour of rich rock stars whose lives are better than mine whining about their pathetic problems, which seemed really boring.”