Metallica: This Monster Lives (27 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

The shoot where James and the band watch the trailer did have one unexpected moment, when Phil, to make a point about the role our cameras could play in Metallica’s emotional development, spoke directly to the camera. “That was interesting for me,” Bob says. “It was the sort of thing that used to freak me out. If someone did that, I’d think, Fuck, you’re not supposed to do that, and whip my camera around. I had to learn that crossing that line is okay. I remember thinking it was pretty cool when Phil did that, but it didn’t make it into the film.” Bob also recalls a similar moment of line-breaking. “James had just laid down some riffs, and someone—I don’t remember who—said to him, ‘You’re the riff master!’ Then Kirk said the same thing to James. Lars, who was in the lower right-hand corner of the frame, looked into the camera, opened his mouth, stuck out his tongue, and pretended to shove his finger done his throat.” Unfortunately, this bit of implied vomiting, so deftly captured by Bob, did not make the cut.

CHAPTER 15

MADLY IN ANGER

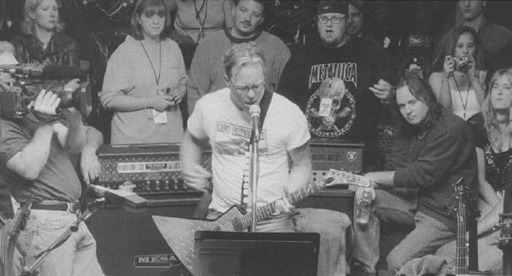

Intercutting “Fan Day” (pictured) with the “Fuck” meeting helped create a third meaning: Metallica showing solidarity in public while crumbling in private. (Courtesy of Niclas Swanlund)

05/20/02

Int. Kitchen, HQ Recording Studio, San Rafael, CA - Day

PHIL:

Try this simple way of looking at things: We don’t have any intensity about people we don’t give a shit about. There is so much intensity in here now, it fills up every corner of the room. I don’t have that same intensity about the grocer. I don’t have [to worry about] him rejecting me if he’s pissed off at me because I don’t like his fruit or something, you know? The relationships that are the most intense are the ones where we have the most to lose. And there’s a huge opportunity here, you guys. If you broke up, you would carry with you all this unresolved stuff. This is a special, unique relationship that deserves a higher standard. The reason why it’s so painful is because you guys haven’t had the courage to get to the treasure that’s there. You’ve been trying really hard to bury it. It’s almost like you do everything you can to not see the love. Every time you try to avoid it, the pain gets worse. The degree of pain you feel is the degree of love that’s not being enjoyed. I stand on that, on the record.

JAMES:

Yeah, it’s easier for me to care about the grocer.

James was back, and our film was still happening, but there was still quite a bit of turmoil in both the Metallica and filmmaker camps. After limiting our shoots to once every four to six weeks for the past year, we threw ourselves back into filming, rolling our cameras every other week—more often, if circumstances dictated. Unfortunately, they rarely did. When I heard about James’s return, I had thought our leap of faith in sticking with this project had paid off, but the future of this film—still officially a promotional vehicle—remained in doubt. There just wasn’t much going on.

We were all elated to have James up and running, but after a week or so of sunny vibes between James and the rest of Metallica, the honeymoon was clearly over. James’s guitar playing on his first day back was, as Bob Rock puts it in

Monster

, “the best sound I’ve ever heard in my life,” but the band as a whole wasn’t making much noise. Instead of hitting the ground running by picking up where they’d left off with the Presidio songs, they began their new chapter by working on some Ramones covers for a tribute album that Rob Zombie was putting together. The mood in the studio was icy. There was a lot of seething resentment toward James that had not yet found an outlet. It looked to me like Lars and James were having trouble even being in the same room together. If Phil wasn’t around as a buffer, they barely spoke.

The therapy sessions were just as listless. Despite the new homey locale, the move from the Ritz-Carlton to HQ seemed to increase the tension. Metallica had sunk a lot of money into HQ, and each session was a reminder that their investment wasn’t paying any dividends in new music. For the first time, I wondered if too much of Phil was a bad thing for these guys. With the luxury of having as much therapy as they wanted, they were spared the need to hunker down and really work things out. Bruce and I like to think that our films transcend their subject matter in order to shatter stereotypes, but unless the Metallica guys stopped bickering and started getting healthy, we feared that this Metallica project might merely confirm stereotypes of spoiled rock stars.

That is, if there was even a band when we were through. All this inertia did not bode well for Metallica’s future: After weathering so much turmoil, it seemed like Metallica was withering away. Never mind whether they’d finish

the album—it seemed to me like they might be finished as a band. Nowhere was this dissolution more visible than in the demeanor of James Hetfield. Everything about him seemed different. He carried himself like he was beaten down, with all the life sucked out of him, and he adopted an oddly bookish air. Most of the rock-and-roll facial hair was gone, and he’d taken to wearing thick-rimmed glasses. Who would have guessed that James Fucking Hetfield would make himself look like a math teacher?

As the band chose fading away over burning out, the real drama was happening on the other side of the camera. I said earlier that I feel like the filmmaking gods consistently smile upon Bruce and me by providing us with great situations to film. These deities also extract a heavy toll. Each of our films has had its own health issues. Making verité films requires a considerable physical commitment. You need to be prepared to stand around for long periods under less-than-ideal conditions, dragging your equipment and yourself around in search of a story that may not reveal itself for hours or days or weeks. Over the years, Bruce and I had fully immersed ourselves in whatever subject matter we happened to be filming. We once worked on a piece about homeless people in New York for a now-defunct ABC newsmagazine show called

Turning Point.

One day I interviewed someone who, in the course of the interview, mentioned that he was HIV-positive and had tuberculosis. At the precise moment he informed me of his condition, a piece of spittle flew out of his mouth. Time slowed as I watched it travel through the air and land right on my lips. I willed myself to maintain composure for the sake of the interview, but inside I was freaking out. I’m germaphobic even under the best conditions, so I was convinced I’d just condemned myself to death.

Bruce’s health problems have actually been quite serious. He was diagnosed with diabetes while we were editing

Brother’s Keeper.

I’ve always felt a little guilty about that, because I suspect that the process of making the film may have exacerbated the onset of the disease. During the time we spent in upstate New York, we ate a lot of greasy food and both gained weight. With

Paradise Lost

, it was the postproduction process that nearly did us in. We ran ourselves ragged trying to complete the film in time to be shown at the Sundance Film Festival. On a rain-soaked gloomy New York day, Bruce went to pick up the film from the negative cutter. He had to take it across town to do a film-to-tape transfer, but the rain made getting a cab impossible, so he wrapped the film canisters in garbage bags and trudged to the subway. Ten days later, two days before we were supposed to leave for Sundance, Bruce

began feeling extremely congested and also experienced searing back pains. He went to the doctor, who diagnosed Bruce with pneumonia, prescribed antibiotics, and suggested he delay leaving for a couple of days. I traveled to Utah for the festival without him. Over the next few days, Bruce’s pain became unbearable and he checked himself into a hospital. He was losing weight and sweating profusely. Bruce underwent a painful procedure in which a hole was drilled through his back to remove a buildup of pus, but he continued to get worse. The doctors were stumped, even suspecting that Bruce might have tuberculosis or HIV. Those tests came back negative, but by this point Bruce was in such bad shape that they hooked him up to an IV to receive antibiotics intravenously. His condition finally stabilized, and after eleven days, the doctors told Bruce he could recover at home, just in time for him to miss the entire festival. The best diagnosis they came up with was that Bruce had picked up an airborne virus from someone coughing in the subway on that rainy day (which is why Bruce, to this day, refuses to take the subway). The day before he left the hospital, I called to tell him

Paradise Lost

hadn’t won any Sundance awards. Bruce spent the next two weeks at home hooked up to a portable IV but he emerged from his ordeal fully recovered.

Bruce developed a more mysterious ailment during the filming of

Monster.

Around the time of James’s return, he began to feel a pain in his leg that erupted when his leg touched anything else. Even drawing bed sheets over it was an excruciating experience. Again, doctors were mystified. Although they suspected a diabetes-related condition, tests were inconclusive. I was convinced that Bruce was experiencing circulatory problems common to diabetics and would eventually be forced to have his leg amputated. I was concerned that he was eating too much sugar and generally not taking care of himself. His doctor prescribed Percocet for the pain, and I was certain he was too dependent on it. I talked about Bruce’s condition with his wife, Florence; my wife; and Bob Richman. We all agreed he should stop coming to shoots until he felt better and should perhaps try to cut back on the painkillers.

Bruce and I typically do all our shoots together. On

Monster

, the unusually large number of shoot days (180) meant that we were each scheduled to do about twenty shoots on our own. Bruce absolutely refused to miss any of the shoots, no matter how bad the pain became. I wanted to cover Bruce’s shoots, but his absolute commitment was complicated by some of my own work commitments. Just before James’s return, before we knew he was coming back, I got fed up with turning down so much work and took on an HBO project about

the parole system. The idea was to follow inmates who were up for parole from various prisons around the country and document the result of their parole hearings. The project dragged on for several months longer than I thought it would, which meant I was often shuttling between

Monster

and the HBO film.

Bruce went to all his shoots but tried to stay off his feet as much as possible. That’s why he was sitting on the couch on a day when I was in L.A. and things with Metallica got a lot more interesting. It was the day the simmering resentment boiled over.

I can honestly say without exaggeration that every shoot we did for

Monster

yielded at least one moment that we couldn’t believe we were lucky enough to get. The problem with turning the 1,600 hours of footage into a film had nothing to do with finding diamonds in the rough; the challenge was finding a sack big enough to carry all of them. More to the point, the problem was figuring out how to string hundreds of disparate moments together, since there was no obvious structural device, such as a murder trial, on which to build the film. Some shoots yielded an inordinate number of diamonds, and these presented a particularly vexing challenge. A good example was the scene that many people who see

Monster

reflexively call the “fuck” scene, because of the amount of times Lars utters that particular epithet.

One condition of James’s recovery after rehab was that he work only four hours a day. Requiring that all recording take place between noon and four was bound to be the proverbial camel’s-back-breaking straw, the thing that would make all the seething resentment explode out in the open. It would have been one thing if James had simply said that

he

wasn’t available before noon or after four, or even that this period should be the only time when anyone laid down any musical tracks. Although you can see, in

Monster

, Lars’s skeptical reaction when James tries to explain how this new rule might actually make the band more productive, the edict might have been allowed to stand—after all, everyone wanted James’s transition back into Metallica to go as smoothly as possible. No, the real problem was that James wanted

anything related to the making of the new Metallica album

to cease when he wasn’t around. Clearly, this was not going to fly.

The debate over the conflict boiled down to an issue of control. James felt that any progress made on the album in his absence meant that decisions were being made without his input. Even the act of listening to rough mixes, if done without

James there, was a form of exclusion. To the others, especially Lars, James’s draconian rule felt like his way of exerting inordinate control over the process. So the stage was set for a battle over who got to control the making of Metallica’s new album. After a few days of snide remarks and pointed asides, the argument came to a head during a therapy session. This is what you see in

Monster:

JAMES:

I felt like it was an agreement. We were gonna work from twelve to four, and then we would not work.