Mieko and the Fifth Treasure (2 page)

Read Mieko and the Fifth Treasure Online

Authors: Eleanor Coerr

“You will feel better tomorrow,” said Grandpa.

Mieko hung her head, knowing that they did not understand. How could tomorrow be better? She would never paint word-pictures again, and she would never feel the joy of having the fifth treasure. She would hear the bomb over and over again, and know that things at home would never be the same.

After supper they all had baths in the backyard tub and put on cotton kimonos. Then they sat outside to enjoy the evening breeze. Twilight fell and crickets began to sing. Mieko thought they sounded sad.

Grandpa pointed to a large rock in the tiny garden behind the house.

“See that?” he said proudly. “Last year I hauled it down the mountain in the cart. Mieko, can you read the words carved into my rock?”

Mieko studied the strokes that formed the word-pictures, but they were difficult to make out. She shook her head.

“ âSpilled water never returns to the glass,' ” Grandpa explained. “It means that one should not worry about things that cannot be changed.”

He paused to puff on his cigarette. Then he went on, “Like Japan losing the war. Like all that has been lost or hurt by the bomb.” And glancing quickly at Mieko, “Like your hand being injured, and your parents sending you to us.”

Grandma smiled, patting Mieko's shoulder. “I know it's not easy for a ten-year-old to understand, but you must try.”

Mieko blinked back the tears. She did not want to understand. The only thing she wanted was to be back home, with everything like it was before.

At bedtime Grandma laid out a futon and hung a mosquito net over it for Mieko.

When she saw the four treasures on top of the chest, Grandma nodded approvingly. “I see that you did not forget your calligraphy supplies. Good. You will soon be practicing again.”

“No, I won't!” Mieko burst out. She shoved the four treasures into a drawer. “The bomb spoiled everything, Grandma. I'll never, never paint again.”

“Don't talk like that,” Grandma said, flustered. “Your hand will get better ...”

“But my fingers will always be stiff and awkward like dried-up shrimp,” Mieko said in a small voice. “And my brushstrokes will look like sticks.”

She threw herself onto the futon and pulled the sheet up over her head.

Grandma sighed.

“I'll write to your parents and tell them that you arrived safely,” she said, turning out the light. “Good-night.”

It was the first time Mieko had ever been away from home alone. She longed for her own bedroom, where her teacher's painting hung on the wall and Mother's peach tree rustled its leaves outside her window.

What if something happened to Mother and Father? What if they got sick and died? What if she never saw them again? Finally, exhausted, Mieko stuffed a pillow against her mouth and cried herself to sleep.

That night she had a nightmare. A plane was droning overhead and then a big bomb exploded in her face. Mieko woke up screaming.

Grandpa knelt by the futon.

“The war is over now,” he said, putting his arms around her. “There are no more bombs.”

But Mieko could not stop the sobs shaking her whole body.

“Shhâshh! You must stop crying,” Grandpa whispered. “Your tears will not help those who were killed by the atom bomb. Their souls must swim across the River of Death to heaven. Every tear you shed drops into the river and makes it deeper.”

Mieko shuddered, imagining what it would be like to struggle in that icy cold water. Gradually, she became quiet.

Grandpa straightened the bedclothes.

“Enough of dreary thoughts,” he said. “Try to sleep like my rock in the garden.”

As soon as he was gone Mieko went to the open window. She pushed up her bangs, letting the night air cool her damp forehead. With no moonlight Mieko could barely see Grandpa's rock. She was sorry for it, so awfully alone out there in the swallowing dark. It looked as alone as she felt.

TWO

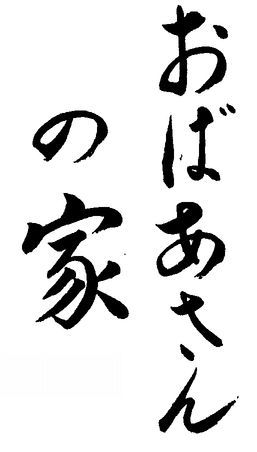

GRANDMA'S HOME

Every morning Mieko put on the dress that Grandma had sewn out of an old summer cotton kimono. It had no buttons or belt so that Mieko could easily slip it over her head. Grandma had taken the long-sleeved blouses and baggy trousers that Mieko had brought and put them into the scrapbag.

“I don't understand why the government made girls wear those hot, prickly outfits,” she said. “Thank goodness the war is over and you can put on decent clothes again.”

She sat back on her heels and looked Mieko up and down.

“Much better,” she said with a satisfied smile. “Yes, Mieko, you look like a girl again.”

There was always much to do around the farm. Grandma never seemed to stop workingâcooking, cleaning, sweeping, or mending. Mieko tried to help. She fed the chickens, collected eggs, polished the wooden porch, lit the fire underneath the deep bathtub in the afternoon, and sprinkled water on the cracked dry earth of the road to keep the dust down.

Kitchen work was the most difficult because Mieko's hand was clumsy and it hurt whenever she tried to hold a knife or spoon. She took a long time slicing eggplants and cucumbers with her left hand.

Once Mieko dropped a whole dish of chopped fish onto the floor. She stood there looking down at the mess, biting her lip.

“I'm not good for anything!” she cried.

Grandma scooped up the fish, talking all the while.

“Never mind, Mieko. It's just a little thing. When the doctor came last week he said that your hand will soon be as good as new. Then you will have no more accidents. ”

Mieko was silent. She knew it would never be as good as new.

As the summer days dragged on, Mieko worried more and more about school. Her grandparents had not mentioned it, and she hoped that they had forgotten.

But one muggy September morning when they were eating rice and miso soup, Grandma calmly said, “Mieko, you will be going to school next week. ”

Mieko almost dropped the porcelain spoon that she was trying to carry to her mouth. She was not hungry any more.

For several moments there were only the sounds of a farm morningâhens clucking and birds scolding in the garden.

Grandma and Grandpa exchanged worried glances.

“You must go to school,” Grandpa said. “It is important to keep up with your studies.”

Mieko knew all that. But a strange school? With children she did not know? And with a hideous, twisted hand?

“Maybe they won't like me, ” she said in a low voice.

“Not like you!” Grandma's bright eyes sent off sparks. “Why would the others not like you? You are a nice girl with good manners and new clothes. ” And she brought out a school uniform, neatly sewn and pressed.

“Here!” She handed it to Mieko. “I made it for a surprise. Go try it on.”

Mieko did not like that kind of surprise. Trembling, she slowly pulled on the navy skirt and white blouse that smelled of camphor.

“I saved these pieces of cloth all through the war, ” Grandma said, giving the skirt a tug to straighten it. She beamed. “A perfect fit.”

Mieko lowered her eyes. “Thank you, Grandma,” she murmured.

Â

The first day of school arrived. That morning, Mieko came into the kitchen, looking a little pale.

“I think I'm getting some kind of germ,” she said, coughing. “My throat is sore. I think I'm coming down with mumps.”

“Open your mouth and say ahhhh, ” Grandma said in, her no-nonsense voice.

She held Mieko's tongue down with a spoon and peered inside. Then she felt Mieko's neck.

“Your throat is fine, and your glands are not even the tiniest bit swollen.”

“Do I have to go today?” Mieko pleaded. “Do I, Grandma?”

Grandma paid no attention. She continued stuffing rice into beancurd envelopes that looked like fat sails. Then she packed them neatly into a lunchbox.

“Such heat!” she said, dabbing at her neck with the edge of her apron. “Mieko, don't walk too fast this morning. ”

“I don't even know where the school is, ” Mieko said. “And ... and I might get lost.”

“I will take you there on my way to the field, ” Grandpa interrupted. “Now scoot upstairs and get ready.”

“Don't forget your art supplies, ” Grandma called, putting a piece of dried fish into the lunchbox for a treat.

Mieko thought it was silly to bring the four treasures when she was not going to use them. But to please Grandma, she stuck them into her black leather schoolbag.

She took such a long time getting ready that Grandpa finally stomped upstairs. Mieko was combing her hair and fussing with her uniform.

“Come on!” he said firmly. “You don't want to be late on your first day.”

“It is the first day that is so scary,” Mieko wailed. “I will sit in the wrong seat ... say the wrong things ... and everyone will stare at my hand.”

Mieko thought that the new puckered red skin looked even worse than the scabs that were coming off.

But there was no escape. She trudged alongside Grandpa to school, clutching his work-roughened hand all the way. When they got there, she hung back.

“Go on in,” Grandpa said, giving her a gentle push. “You will be all right. ”

Mieko watched him stride away until he turned the corner. For an instant she stood there, paralyzed with fear. Then she took a long, shaky breath and walked slowly through the doorway.

THREE

SCHOOL

Mieko slipped out of her geta and put them in one of the shoe boxes in the hall. She wiped her moist hands on her skirt and shifted from one foot to the other, waiting for a teacher to come along and direct her to the right classroom. She pictured her teacher looking old and mean.

Out of the corner of her eye Mieko saw the students come in, some laughing, some arm-in-arm. They had lived in the town all their lives and knew each other well. Nobody spoke to Mieko.

It was a pleasant surprise when a pretty young woman introduced herself.

“You must be Mieko,” the teacher said warmly. “Your grandfather told me about you. I am Miss Suzuki. ”

After bowing politely, Mieko followed Miss Suzuki into the classroom to a desk near the back. She gave Mieko a stubby pencil, carefully sharpened at both ends, and some pages of an old newspaper.

“Try to write in the white spaces,” Miss Suzuki said. “I hope we will be getting more supplies now that the war is over. Until then, we must make do.”

As Mieko looked around at all the unsmiling faces, she knew more than ever what loneliness meant.

“We have a new pupil,” the teacher announced. “Mieko, please stand up.”

Her knees shaking, Mieko got to her feet as thirty pairs of eyes gazed at her. She blushed and tried to hide her hand behind her back.

“Let's make her feel welcome,” Miss Suzuki went on. “She has just come from a town near Nagasaki, and I expect all of you to help her get acquainted with our school.”

This caused a buzzing in the room. As Mieko sank back into her chair, she heard whispers.

“That's where the big bomb exploded ... Look at her hand ... It makes me sick. ”

Mieko felt smaller than a fly. Just because no bombs had dropped on this part of Japan was no reason to be stupid. She wanted to scream “Stupid!” at them all. But she swallowed the word. Mother had often warned her that a nasty word was like a birdâonce it flew out of her mouth it would never fly back. Mieko pressed her lips together so that the word could not escape.

Â

During the morning, Mieko tried hard to concentrate, but Akira made it impossible. He was a skinny boy with stiff short hair that stood up like a brush and he wore black-rimmed glasses.

Other books

Pack Beta (Were Chronicles Book 11) by Crissy Smith

Distracted by Warren, Alexandra

Roc And A Hard Place by Anthony, Piers

Cyndi Lauper: A Memoir by Lauper, Cyndi

Sleepwalking by Meg Wolitzer

Out of Bounds by Dawn Ryder

The Ghosts of Now by Joan Lowery Nixon

Darkness Descends (The Silver Legacy Book 1) by Alex Westmore

Tourists of the Apocalypse by WALLER, C. F.

Unable to Resist by Cassie Graham