Mira's Diary (4 page)

Authors: Marissa Moss

Then Claude listed names I knew, names everyone knows. Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin, Mary Cassatt, really famous painters. I started paying attention.

“Who is this artist you work for?” I asked.

“Monsieur Degas. He is a genius.”

Degas? I had a print of one of his paintings,

The

Dancing

Lesson

, in my room. Mom had taken me to the big Impressionist exhibit in San Francisco last year. If I knew what was going on, I could be excited about this time-travel thing. But I was too scared and too angry. The only thing that kept me calm was the warmth of Claude's arm linked in mine.

Claude opened the door to a small two-story house, leading me into a room full of chairs, a sofa, and, most of all, paintings. Small sculptures of horses and women were scattered on shelves, tables, and chairs, some in clay, others in plaster or bronze. There was something raw about these figures. You could see the marks of fingers pressing into the clay but instead of looking clumsy, the handling gave the pieces an incredible energy, an urgency. One horse looked like it would leap off its base and gallop around the room. A woman in a tub twisted to scrub her back, and I could swear she moved, she seemed so alive.

All over the walls were pictures that in the future would be in museums. Some I could tell were by Degas, ballet dancers like my poster, women bathing or trying on hats. But a lot of them weren't. If I'd taken that art history class Mom wanted me to, I'm sure I could have named the artists. The only one I knew for sure was Van Gogh. No one has such thick, globby brushstrokes, such strange greens and yellows as Van Gogh.

Besides the paintings, Japanese prints were tacked onto the walls, and piles of books teetered on the floor and on shelves. It was all a mess, but the most artistic mess I'd ever seen.

“Sit.” Claude steered me into a chair next to a small statuette of a rearing horse. “I will ask the housekeeper to make us some tea.”

The letter was smoldering in my fingers. Even with so much to look at in the room, I couldn't wait any longer. As soon as Claude left, I tore open the flap and pulled out the single page.

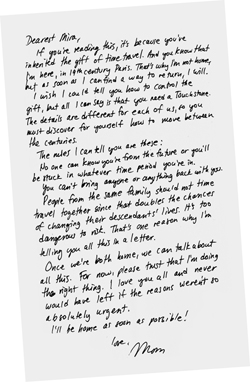

Dearest Mira,

If you're reading this, it's because you've inherited the gift of time travel. And you know that I'm here in nineteenth-century Paris. That's why I'm not home in Berkeley, but as soon as I can find a way to return, I will.

I wish I could tell you how to control the gift, but all I can say is that you need a touchstone. The details are different for each of us, so you must discover for yourself how to move between the centuries.

The rules I can tell you are these:

No one can know you're from the future, or you'll be stuck in whatever time period you're in.

You can't bring anyone or anything back with you.

People from the same family should not time-travel together since that doubles the chances of changing their descendants' lives. It's too dangerous to risk. That's one reason why I'm telling you all this in a letter and not in person.

Once we're both home, we can talk about all this. For now, please know that I love you, Malcolm, and Dad. I would never have left if the reasons weren't so absolutely urgent. Trust me to find my way back to you as soon as I can.

Love,

Mom

The letter raised more questions than it answered. Why had she traveled to Paris, 1881, in the first place? Why didn't she tell us she

could

time-travel, that I might be able to too? What about Malcolm? Dad? Were they here somewhere and I needed to find them? And what was a touchstone? How was I supposed to figure out where one was and how to use it?

I read the letter through a second time, searching for answers in what she didn't say, but this time all I noticed was the rule about people who are related not traveling together. I didn't get how stopping to talk to me would change anyone's future. What was so risky about that?

Stupid rules, with no useful information at all. But I had to admit, I was relieved. She hadn't cheated on Dad. She hadn't run away from us. She was stuck in another century. With me, which meant I wasn't alone here. And I would be able to get home somehow. I just had to find a touchstone, whatever that was.

There was something else about the letter that gave me a hint of satisfaction, even as I worried about how I'd ever get home. Mom said I'd inherited her ability to time-travel. So maybe I wasn't pretty, smart, or artistic, but I had something from her.

Now here I was in a house full of great art, about to meet one of the most famous painters of all time. It seemed ironic that the gift I'd actually gotten from Mom showed me how much I hadn't inherited the artistic talent I'd always secretly wanted. Looking at the pictures around me, I knew I'd never come even close.

Claude came back with a clattering of cups on a tray. I folded the letter up and stuck it in my sketchbook. I didn't have a pocket, a purse, a backpack. What else was I supposed to do?

“Why were you so angry with that man and woman? And what means âmom'?” Claude handed me a teacup with a gilt filigreed handle.

“Mom, you know, that's English for thief, pickpocket,” I lied. “She stole my purse when I was on the train. Which is why I have no money.” The excuse just popped into my head and Claude seemed to believe it. I wished I could forget about Mom, forget about the letter, and just enjoy being with him. I liked the way he looked at me, like he was really paying attention, like he cared what I said. But I couldn't shake off how angry I was. And under the rage was a sharp sliver of fear. What was I doing here?

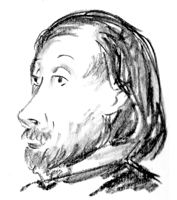

I was saved from any more awkward explanations by Monsieur Degas. He was tall, thin, and stoop-shouldered, with a long nose and full lips. But what I noticed most were his eyes. They looked right into you like they saw into your soul. But in a nice way, as if you were sharing a joke.

“Claude,” he said. “

Veux-tu faire la présentation?

”

“I beg pardon, monsieur. This is Mademoiselle Mira. She is American and in need of a place to lodge. I thought perhaps she could stay here. Mira, this is the eminent painter, Monsieur Degas.”

Claude had stood up, so I did too. I was so nervous that my cheeks were hot and pink. “I'm honored to meet you, monsieur,” I said, not sure if I should offer my hand to shake or curtsey or bow or who knows what.

“The honor is all mine.” Degas dipped his head in a short bow and gestured for me to sit again. He folded himself up into a chair, looking far too tall and angular for its roundness, stroking his chin with his elegant fingers. I have this thing about hands. Some are stubby and thick; other people have flat, shovelly fingers, and then there are hands like Degas's. His were supple and intelligent. I could imagine them shaping the sculptures all around us.

“How is it that you speak English so well?” I asked, ashamed of my few words of French.

“I have family in your New Orleans, and I have spent many happy months visiting them. I must say I love the English language! I am enchanted to have the occasion to practice it with you. Do you know my favorite phrase at the moment? Turkey buzzard! Such a marvelous sound! Do you know them, the turkey buzzard?”

I was talking to a famous artist about turkey buzzards?

“I have seen them, but it is not the bird itself which interests me,” Degas continued. “They are rather ugly, you know. But what a wordâturkey! And buzzard! And then, you have the two togetherâturkey buzzard!”

“And what do you call them in French?” I asked.

“Turkey buzzard!” laughed Degas. “Because they do not exist here, so we have no name for them. Like that other creature that is so distinctly American, the one with the white stripe on its back and the foul smell when it is fearful.”

“A skunk?”

“Yes, a skunk! Now that is another marvelous word. Skunk!”

And the way he said it, it was. Degas was funny and gentle and curious about me. I didn't have to worry about what to say because he asked me questions and all I had to do was answer.

For some reason I'd always thought he was an old crank who painted beautiful pictures, a lonely old bachelor who hated people. But from the way he talked, he had loads of friends and went out almost every nightâto the opera, the ballet, the symphony, gallery exhibitions, dinner with friends. I liked him not just as an artist, but as a person. He was so easy to talk to that I almost told him the truth about who I was and whereâI mean, whenâI really belonged.

But I remembered Rule Number One and said I was supposed to be with my aunt, only she'd been called away to visit a sick friend in Italy. There was no room for me to go with her and I really wanted to see Paris, so my aunt was supposed to arrange for my hotel and I'd wait for her here. Only it seemed like my aunt had forgotten and there was no hotel. Normally I'm a terrible liar, but after the Mom-equals-pickpocket story, I felt more inventive. Degas and Claude both swallowed my story.

“Claude thought maybe I could stay here,” I said hopefully.