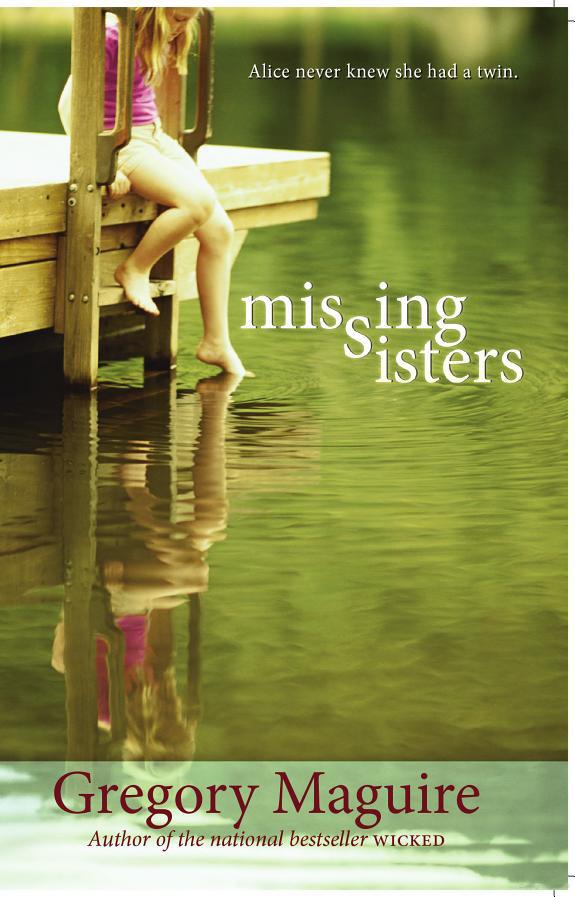

Missing Sisters -SA

Read Missing Sisters -SA Online

Authors: Gregory Maguire

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fiction, #General, #Family, #Social Issues, #Social Science, #Siblings, #Sisters, #Twins, #Historical, #Orphans, #Family & Relationships, #Orphans & Foster Homes, #Special Needs, #Handicapped, #People With Disabilities, #Adoption

| Missing Sisters -SA | |

| Stand Alone (Children) [0] | |

| Gregory Maguire | |

| HarperCollins (1994) | |

| Rating: | ★★★★☆ |

| Tags: | Juvenile Fiction, Fiction, General, Family, Social Issues, Social Science, Siblings, Sisters, Twins, Historical, Orphans, Family & Relationships, Orphans & Foster Homes, Special Needs, Handicapped, Adoption, People With Disabilities |

Affectionate humor and a particularly well-defined setting lend distinction to this touching novel set in 1968. Alice, a 12-year-old beset by hearing and speech impediments, lives in an orphanage run by nuns in upstate New York. After Sister Vincent de Paul, Alice's closest friend and supporter, is severely injured in a fire, no one explains to Alice that the sister has been sent for a long stay in a nursing home. Alice, worrying that Sister Vincent has died, makes a pact with God: until she knows that Sister Vincent will recover, she won't even consider an offer of adoption that has been extended to her--her first. A girl Alice despises gets her place, but Alice has a drama of her own, inadvertently learning that she may have a twin sister. With a mixture of cunning and courage, Alice finds her. Maguire, who spent some of his childhood in a Catholic children's home, avoids pat and obvious resolutions, and he conveys Alice's faith lightly but substantively. Characterizations of the Catholic environment are sharp and funny. Some poignant, genuinely suspenseful moments express, among other truths, the value of individuality. Ages 10-14.

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Grade 5-7-A portrait of a 12-year-old handicapped girl, raised by a stern group of nuns, emerges from this ragged novel. Alice has spent her life in an orphanage, steeped in rigid religiousness and-because of her hearing and speech impediments-in confusion. When the one nun who is sensitive to Alice tragically vanishes from her life, the girl's isolation is compounded by grief. Then, through a fluke of mistaken identity, she discovers that she has an identical twin sister who does not suffer from disabilities and who has a loving, supportive adoptive family. As Alice struggles to find her place, the story struggles to deal with attitudes that seem dated and off-balance without really giving a sense of upstate New York in the 1960s. Supporting characters and issues are left dangling, although Alice, finally, is not; her sudden adoption in the last few pages is abrupt and unsettling. An imperfect book, but an unusual look at Catholic family values and at a troubled child.

Susan Oliver, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Gregory Maguire

For Debbie Kirsch, with love

ICE AND F IRE

“Look. Lookit, Sister,” said the girl. She stretched her hands out on either side of her.

“It’s raining out one window and snowing out the other.”

“I’ll look in a minute,” said the nun. “After I get this oil off the burner—it’s popping like nobody’s business.” She hustled the skillet onto the chopping board. “I’ll burn this place to the ground yet.”

“Oh, don’t do that,” said the girl.

“Pray that I don’t,” said the nun. “Say a prayer to the patron saint of stupid people, whoever that might be.” She dried her pink hands on a square of burlap cut from a potato sack.

“Now, what’s to see, Alice?”

“Lookit: snow,” said Alice, pointing out the large windows over the kitchen counter.

Snow indeed. “And lookit: rain.” Across the room and above the sink, the other windows were spattered with raindrops.

“Well, well,” said the nun. “Fancy, you’re right.” She folded her arms across her apron bib for a moment in stillness, not like her. “Isn’t it grand.” In the dawn storm the big kitchen of the retreat house seemed lit with purple. Alice was a twelve-year-old shadow, dark and observant, of ancient Sister Vincent de Paul, who in her black veil and habit and white apron looked like a witch in bandages. Slotted spoons and ladles and strainers hung from a central ring, a kind of chandelier of utensils. Flour from the day’s bread-baking efforts drifted in the air between the windows, an inside weather of white dust. The room smelled of oil faintly scorching.

The other girls and the other sisters were still asleep. Alice thought of them in their beds in the dormitories. Seventeen girls snoring their vacation trip away, while only Alice Colossus was awake and listening. Alice and, of course, Sister Vincent de Paul, who with her bum foot clumped around in a huge shoe like a safe-deposit box.

“You’re very sharp,” said Sister Vincent de Paul. “You’ve a keen eye when you’re on your own, Alice.”

“I’m not on my own,” said Alice. “You’re here.”

“You know what I mean.” Sister Vincent de Paul went to the walk-in refrigerator for eggs. She planted her square shoe like a cinder block and swung the rest of her body around it.

Her skirts swished. Alice tried hard to keep the sounds sure in her mind, for relishing: the thump of shoe, the rustle of black cotton, and behind it the hiss of the two-minded storm. Or perhaps it was the sizzle of oil she still heard. Alice loved to be Sister Vincent de Paul’s helper before the house was up. It was her ears’ clearest time of day.

“Think fast!” called Sister Vincent de Paul from the door, and threw a package of frozen blueberries across the room. Alice saw it before she heard it, but managed neatly to swipe it from the air before it landed on the floor. “Bravo!” chortled Sister Vincent de Paul and returned,

thump rustle thump rustle

, with two dozen eggs.

“Now tell me why you think the storm both rains and snows,” said the nun, cracking eggs with one hand until twenty-four golden suns had flopped chummily in the flour.

“It can’t make up its mind, like me,” said Alice.

“Say it slower. Think your consonants.”

“It—can’t—make—up—its—mind,” said Alice again. If Sister Vincent de Paul would look up, she could easily lip-read what she couldn’t make out by sound. But Sister Vincent de Paul wouldn’t lip-read Alice, because Alice was merely lazy and could do better if she tried.

“The storm can’t make up its mind?”

It had been a joke, but it wasn’t funny the second time. “Storm’s stupid,” said Alice.

“It’s beautiful,” Sister Vincent de Paul declared, poking out the eyes of the eggs with a slotted spoon till they bled yellow. “Are you going to grease those muffin tins?”

“Storm’s mixed up,” said Alice. “Like me.”

“The storm,” said Sister Vincent de Paul—and then a crash of thunder announced an opinion—“the storm is brilliant! Like you!” There was lightning, and more thunder. The snow was dancing in spirals. Around and down, more and more. The rain out the other window spattered all the harder.

“The line of snow cloud must be just above this room,” said Sister Vincent de Paul, sprinkling a little flour onto the breadboard, lifting a spoon, and pointing heavenward. “It’ll shift in a moment. We’re at a miraculous juncture. As usual. Warm front and cold front having a stare down directly overhead. And only you and me to notice, Alice.” Alice missed some of this. She rubbed Crisco into the muffin tins. “It’s just a cloud,” she said.

“And you’re just a girl, and life is just life,” said Sister Vincent de Paul gaily. “And the morning bread just feeds us daily so we may notice such goings-on!” She began to sing in a sort of off-center way—her voice was riding the melody like a kid on a bicycle for the first time, whoopsing and wobbling along. “Then sings my soul, my Savior God, to Thee. How great Thou art, how great Thou art!”

Alice hummed a little to herself. The lightning stitched a path between snow and rain, the thunder kettle-drummed. The kitchen lights flickered and went out just as Sister Vincent de Paul was returning the pan of oil to the burner. “Oh,” said Alice. “Mercy!” said Sister Vincent de Paul. The skillet bumped into the corner of the stove, and a long silver tongue of oil sloshed out.

In a moment the counter was on fire. Small yellow-blue flames ran up the wall like morning glories growing on a trellis in a hurried-up nature movie.

“Salt,” snapped Sister Vincent de Paul. Alice ran for the butler’s pantry and came back with six saltshakers, not one of which held more than a teaspoon. She began to untwist the caps.

“No, the salt in the canister!” said Sister Vincent de Paul, beating at the fire with her apron. Alice hadn’t remembered the canister.

But salt didn’t do it, and the fire extinguisher’s help was only limp and sputtery. “Alice, you must run and wake everyone.” Sister Vincent de Paul was yelling to be sure she was heard.

“And call the fire brigade!”

Alice couldn’t do the phone. For some reason she couldn’t hear well over wires and through the little dots in the ear-piece. So she stumbled through the swinging door and across the refectory, past the twenty-five places set at the two long tables. Skidded on the circle of braided rug in the hall and turned the corners on the big, carved staircase like a pro. Her long legs drew her up four steps at a time.

Rachel Luke and Esther Thessaly were coming back from the john together (they were supposed to call it the jane, since John was an evangelist and apostle, but nobody did). Sister Isaac Jogues was wafting up and down the corridor with her nose in her breviary, muttering matins. Hadn’t they noticed the lights go off? “Ahh,” said Alice. “Fire in the kitchen! Wake up!” Rachel and Esther, who were only about eight, clutched each other and said, “What’d she say?” But Sister Ike dropped her breviary to the floor and strode like a linebacker down the corridor toward Alice. “Fire! Where, Alice?”

“Wake up, wake them up!” Alice said wildly, tearing from Sister Ike’s grasp and turning into the older girls’ dormitory. “Fire in the kitchen! Don’t anyone hear me?

Fire!

” The clock in the hall chimed six and three quarters. Alice could hear its bonging, like an angel’s announcement of the hour of death. Domestic thunder. Sister Ike had roused Sister John Bosco, who appeared without her wimple, showing spikes of silver hair and putting to rest for all time the rumor that she was bald as a basketball. Alice had gabbled her message more and more clumsily at the groggy girls. In a tatter of nightgowns, habits, and even four-year-old Ruth Peters in her shameful soiled diapers, they lined up and counted themselves and marched single file down the right-hand side of the stairs, no talking and no running. Sister Francis of Assisi soon hoisted the sobbing Ruth in her arms, thinking nothing of the stink, or maybe just offering it up.

Sister John Bosco and Sister Francis Xavier had run on ahead to the kitchen, from which large balls of black smoke emerged and changed shape in the air. Alice said, “Phone!” but it turned out the phone lines had been cut, too, perhaps by the same tree limb that had downed the power lines.

They were unsure what to do. Outside it rained and snowed, back and forth like armies advancing and retreating, not only on the odd, steep roofs of the retreat house, but on the pine-toothed hills and stubbled meadows of the desolate country of God. There wasn’t a farmhouse within a twenty-minute walk, and the hamlet with the fire station seemed so far away as to be in another century, beyond decades of snow-drift and ice. The city of Troy, where they usually lived, was like a past life, two hours away. “Girls, into your boots and coats,” said Sister Jake, but where were they to go?

By the time the upstairs clock struck seven, all the girls, including Alice, were swaddled in wool coats and scarves and sweating like mad, standing in two rows just inside the French doors and floor-to-ceiling windows. You couldn’t even see the lake, just fifty yards down the slope. Sister Jake kept counting the girls obsessively, as if one might be missing, but she came up each time with eighteen, which was the right number.

She called them by name. The girls had Old Testament first names and New Testament surnames; they were Sarahs and Ruths and Naomis and Miriams. Alice’s first name, a quirk in the pattern, had come from a benefactress of the Sacred Heart Home for Girls, and her last name from St. Paul’s letter to the Colossians. Alice Colossus.

Alice Colossus. A kind of grade-school Frankenstein orphan: tall, pretty deaf in a crowd, weird. While Sister Jake counted the girls, Alice counted the nuns.

The nuns had the names of men. Sister Francis Xavier, Sister Francis de Sales, Sister Francis of Assisi. (They all called each other Sister Frank, but no one else could.) Sister John Vianney. Sister Isaac Jogues. (Jake. Ike.) Sister John Bosco, the boss nun. (John Boss.) And of course Sister Vincent de Paul.

All seven sisters: three in the kitchen, four in the parlor.

Naomi Matthews, at fourteen the oldest girl, began to pray the rosary, loudly. The other girls took it up, the pattern of their voices familiar to Alice in the rhythm, though not in the meaning.

Braa

na na, na na

naa

, bra na na na NA. Sister Isaac Jogues told them to please hush up while they decided what to do. Naomi Matthews glared pityingly at Sister Ike’s lack of faith in

God

, but dropped her voice.