Modern China. A Very Short Introduction (2 page)

Read Modern China. A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

This page intentionally left blank

Pronunciation

This book uses the

pinyin

system of romanization of Chinese.

Very approximately indeed, the transliterations that cause most problems for English-speakers are the following sounds: c – pronounced ‘ts’

x – pronounced ‘sh’

q – pronounced ‘ch’

And the sounds

chi

,

zhi

,

ri

,

si

,

shi

, and

zi

are pronounced as if the

‘i’ sound is an ‘rr’ – so ‘chr’, ‘zhr’, and so forth.

This page intentionally left blank

List of illustrations

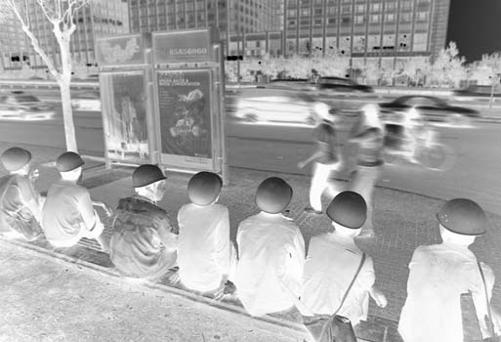

1 Workers waiting to end

8 Mao

Zedong

51

a long day

3

© Hulton Archive/Getty

© Gideon Mendel/Corbis

Images

2 Wealthy Chinese woman with

9 Guard aiming a rifl e at

bound feet

9

a Chinese landlord

© Underwood & Underwood/Corbis

farmer

57

© Bettmann/Corbis

3 Famine victims in China

28

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

10 Chairman Mao with young

students

59

4 British armoured car in

© Bettmann/Corbis

Shanghai, c. 1935

33

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

11 Performance during the

Cultural Revolution

61

5 General Chiang Kaishek,

© Bettmann/Corbis

c. 1930

38

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

12 Tourists take photos,

Shenzhen

66

6 Chinese refugees, Chongqing,

© National Geographic/Getty

c. 1937

Images

47

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

13 Chinese students asking for

democracy

68

7 Mao Zedong on the Long

March, c. 1935

© Peter Turnley/Corbis

49

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

14 Chinese woman’s feet distorted

18 Section of ‘Nine Horses’

by foot-binding

76

scroll by Ren Renfa, from

© Bettmann/Corbis

Master

Gu’s Pictorial Album

(1603)

120

15 Men pulling a plough

86

© Percival David Foundation of

© Christopher Boisvieux/Corbis

Chinese Art

16 Olympic Five Rings

95

19 SuperGirl fi nals

133

© China Photos/Getty Images

© AP/PA Photos/Empics

17 Urban woman protecting

20 Pudong skyline

137

herself from smog

115

© Xiaoyang Liu/Corbis

© Wally McNamee/Corbis

The publisher and the author apologize for any errors or omissions in the above list. If contacted they will be pleased to rectify these at the earliest opportunity.

What is modern China?

It is impossible to do other than assent to the unanimous verdict that China has at length come to the hour of her destiny … The contempt for foreigners is a thing of the past … Even in remote places we have found the new spirit – its evidence, strangely enough, the almost universal desire to learn English … as knowledge of English is held to be the way to advancement, the key to a knowledge of the science and art, the philosophy and policy, of the West.

This assessment comes from the book

New China

by W. Y.

Fullerton and C. E. Wilson. In the third decade of China’s era of ‘reform and opening-up’ (

kaifang gaige

), at last the clichés of the old Maoist era – the Chinese as worker ants mouthing xenophobic anti-imperialist slogans while all dressed in blue serge boiler-suits – have given way to impressions of a country whose cities are full of skyscrapers, whose rural areas are being transformed by new forms of land ownership and a massive rise in migrant labour, and whose population is keen to engage with the outside world after years of isolation. Fullerton and Wilson’s observation that China is reaching the ‘hour of her destiny’, and that a signifi cant part of the population are learning English as one way to fulfi l that destiny, seems a reasonable comment on a China that is clearly very different from the one ruled a generation ago by Chairman Mao.

1

However, Fullerton and Wilson did not pen their observations having landed back at Kennedy or Heathrow airports on one of the many Air China 747s that ferry thousands of travellers daily between China and the West. They wrote their book a full century ago, and their refl ections on what they subtitle ‘a story of modern travel’ came at what, in retrospect, is a particularly poignant moment in China’s history: the year 1910. The China they portray was lively, even optimistic, and very much engaged with the outside world. Yet within a year, the Qing dynasty, the last Chinese imperial house which still ruled the country that Fullerton and Wilson saw, had fallen. The revolution of October 1911 fi nally brought the two-thousand-year tradition of imperial rule in China to an end, making way for a Republic.

That Republic would collapse less than 40 years later, and would be succeeded in turn by a People’s Republic whose own form would change over decades as it struggled to defi ne what

‘modern’ China was. It is a sign of how long it has taken for

hina

China to defi ne its own vision of modernization that a travel description from the early 20th century can still have resonance

Modern C

in the early 21st.

China is the world’s most populous country, with some 1.3 billion inhabitants at the beginning of the 21st century. Its economy grew in the fi rst decade of this century by an average of around 10% a year. It is seeking a regional and global role, with a new political and economic presence in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, and has taken frequent steps to portray itself as a responsible member of the world community, playing a role in troublesome areas such as Iran and North Korea where the West has little sway. The 2008 Beijing Olympics mark the ‘coming-out’ of China as an integrated member of the world community of nations, the acme of the ‘peaceful rise’ which it has been engineering since the mid-1990s. The term ‘peaceful rise’ (

heping jueqi

) itself, associated with the political thinker Zheng Bijian, was thought by Chinese ideologists to be too confrontational, and has been replaced with the term ‘peaceful development’. The idea remains the same, 2

however: that China is fi nally gaining the role as a regional and global power that it lost in the mid-19th century.

Everywhere one goes in China, there are signs of change.

Signifi cant areas of western China have been fl ooded to make way for the massive Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Their former inhabitants are being relocated and urbanized as China moves away from its traditional agricultural past. In the cities, Baidu, a home-grown Chinese internet search engine, dominates the market which is held by the worldwide brand leader, Google, in most other countries. Beneath China’s strict censorship laws lies a ‘grey zone’ of cultural production: from underground movies criticizing the Cultural Revolution to pornography, cultural rebels fi nd ways to make their views known.

What is modern C

China is now a major actor in world markets. Through much of the early 2000s, China’s burgeoning exports led to concerns in

hina?

1. Illegal migrant labourers are a common sight on Chinese building

sites. Their work underpins the futuristic skylines in cities such as

Shanghai and Beijing

3

the US and EU about the Chinese trade surplus. The West was also concerned about the strength of the Chinese currency (the yuan or renminbi) against the dollar, with the Americans and French frequently lobbying the People’s Bank of China to revalue it upwards. The Chinese current account surplus also means that it has had cash to spend on investments around the world, from the US, to Africa, to Russia. Chinese companies bought the assets of the bankrupt British Rover car group in 2005; Chinese capital was offered to help blue-chip UK high street bank Barclays pay for a takeover of a Dutch rival, ABN-AMRO, in 2007.

Yet China is also undertaking one of the most precarious balancing acts in world history. While the country has the fastest-growing major economy in the world, it is also becoming one of the globe’s most unequal societies, even while its policies lift millions out of poverty. For the rural and urban poor, health care and education are available only to those who can pay for them.

hina

China is also in the grip of a resource and environmental crisis.

All across China, power blackouts regularly interrupt industrial

Modern C

production. Globally, the country must scramble for energy and mineral resources. Environmental degradation forces bicyclists to wear smog masks and has rendered the Yangtze dolphin extinct. As global warming accelerates, China is set to become the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

China continues to maintain a one-party dictatorship and heavily constrains political dissent; yet every year, there are thousands of demonstrations against offi cial policies and practice, some of them violent. Corruption also runs rife.

There are signifi cant differences between China at the start of the 20th century, and the start of the 21st. The China of a century ago was the victim of Western and Japanese imperialism, in danger, in the phrase of the time, of ‘being carved up like a melon’ by the foreign powers. It was a weak and vulnerable state. Today’s China, while it has deep frictions and fault lines, is a much stronger entity. Yet the similarities between China now and China a 4

hundred years ago are startling also: political instability, economic and social crisis, and the need for China to fi nd a role in a world dominated, even if less so than in the post-Cold War moment, by the West.

Chinese leaders, who are acutely conscious of history in a way that has been less true of the American and British governing classes in recent years, would also note that the seemingly moribund Qing dynasty had begun to modernize impressively fast in the early years of the 20th century. Nonetheless, it collapsed, as did most of its successor regimes in the following four decades. It is the earnest intention of the rulers of the People’s Republic of China that this fate should never happen to them. To understand their fears and concerns, and to understand China in its own terms, the China of today can only be understood in its historical and global

What is modern C

context. That is what this book tries to do, explaining the reasons that modern China looks the way that it does.

Overall, the book hopes to give a picture of China that refl ects

hina?

three main viewpoints. First, rather than being a closed society, China has almost always been a society open to outside infl uence, and ‘Chinese’ culture and society cannot be understood in isolation from the outside world. In other words, China cannot be treated as a special case of an isolated society, but rather as part of a changing regional and global culture. Second, it is too simple to say that China has moved from a ‘traditional’ past to a ‘modern’ present. Rather, the modern China we see today is a complex mixture of indigenous social infl uences and customs and external infl uences, often, but not always, from the West. Society did not change overnight in 1912 with the abdication of the last emperor, or in 1949 with the Communist revolution, but neither is the modern China of today essentially the same as when the emperors were on the throne a hundred or two hundred years ago.

Third, our understanding of how modern China has developed should not come only through following elite politics and leaders and their confl icts. Instead, we should look at continuities as well 5

as changes in how the Chinese have come to modernity, and the impact of change on society and culture as a whole.

What does it mean to be Chinese?

A hundred years ago and today, an important question remains: What

is

modern China? To come to an answer, we need to spend a little time investigating both terms –

China

and

modern

.

‘China’ today generally refers to the People’s Republic of China, the state that was established in 1949 after the victory of the Chinese Communist Party under the leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong. That state essentially covers the same territory as the Chinese empire under the last imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644–1911), which extended its reach to the west and north of the lands that earlier dynasties had controlled. (The modern state, however, has a fi rm grasp on Tibet, does not lay claim to Outer

hina

Mongolia or the lands in the northeast taken by Tsarist Russia, and in practice does not control Taiwan.) However, this continuity

Modern C

of geography conceals the reality that China has changed shape over the centuries, and continues to do so even now. About 2,500