Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (9 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

In the generation following the disappearance of the Roanoke colony, English settlers established permanent and profitable colonies. Calvinist dissenters came from England in 1620, separatist Calvinists known as the Pilgrims. These first settlers on Plymouth Rock would soon be followed by the Puritans, a much larger sect of dissenting Calvinists, who created the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Puritan ministers saw the founding of the New England colonies as an “errand into the wilderness” to create a Calvinist utopia. Cleansed of the mother country’s flirtations with sin, the New World would become the kingdom of God. To their great horror, the Puritans found their wide-open wilderness full of monsters.

Sex with the Devil

The Puritan settlements of New England have become representative symbols of early American settlement. Although not the first successful settlements in English North America (Jamestown dates to 1607), they occupy an integral place in the memory of the early American experience. There are many explanations for this importance, ranging from the dominance of New England historians and educational institutions in the writing of early American history, to the way the Puritans’ own self-conceptions comport with Americans’ tendency to view themselves as bearers of a special destiny.

28

The special place the Puritans have occupied in American memory made them multivalent signifiers for national identity, appearing as everything from dour-faced party poopers to, ironically, the embodiment of the alleged American appreciation for the search for religious liberty. Their sermons and devotional tracts have provided the grammar of American understanding of sin, redemption, and national destiny, shaping both religious and political consciousness.

No aspect of Puritan experience lives more strongly in American memory than their fear of monsters, specifically their fear of witches

that led to the trials of about 344 settlers during the course of the seventeenth century. The Salem witch trials, an outbreak of Puritan witch-hunting that ended in the executions of twenty people in 1692–1693, has become central to most Americans’ perception of their early history. Salem historians Owen Davies and Jonathan Barry have noted the central role the event came to play in the teaching standards and curriculum of public schools, making knowledge of it integral to understanding the colonial era.

29

For many contemporary people, Salem is read as a brief flirtation with an irrational past. At least some of the interest it garners comes from its portrayal as an anomaly, a strange bypath on the way to an unyielding national commitment to freedom and democracy. On the contrary, Salem was far from the first witch hunt in early New England. Nor did the American fascination with the witch disappear after 1693.

Puritans hunted monsters in the generation before Salem. In 1648 Margaret Jones of Charlestown, Massachusetts, became the first English settler accused of witchcraft, and later executed, in New England. The

Massachusetts Bay Colony’s first governor, John Winthrop, called Jones “a cunning woman,” someone with the ability to make use of herbs and spells. Jones was further alleged to have had a “malignant touch” that caused her erstwhile patients to vomit and go deaf. Winthrop, after a bodily search of Jones by the women of Charlestown, claimed that she exhibited “witches teats in her secret parts,” which was, by long established superstition, the sign of a witch. The Puritan judiciary executed Jones in the summer of 1648. More trials and more executions followed.

30

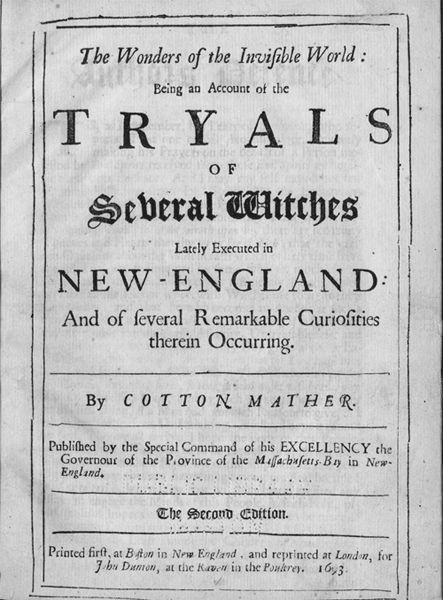

Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World

The witch embodied all the assorted anxieties that early New England settlers felt about their new environment, their personal religious turmoil, and their fear of the creatures that lurked in the “howling wilderness.” The Puritan movement in England grew out of the fear that the English Church retained too many elements of the “satanic” Roman Catholic Church. The Puritan conception of the spiritual life, embodied in John Bunyan’s

The Pilgrim’s Progress

, imagined the Christian experience as a war with monstrous beings inspired by the devil. This understanding of Christian experience as a struggle with the forces of darkness made its way to the New World. Not surprisingly, this new world became a geography of monsters in the minds of many of the Puritans.

Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather helped to construct a New World mythology that not only included the bones of antediluvian giants but also the claim that native peoples in North America had a special relationship to Satan. In Mather’s New World demonology, the Native Americans had been seduced by Satan to come to America as his special servants. This made them, in some literal sense, the “children of the Devil.” Other Puritan leaders reinforced this view, seeing the Native Americans as a special trial designed for them by the devil. Frequently, Puritan leaders turned to Old Testament imagery of the Israelites destroying the people of Canaan for descriptions of their relationship with the New England tribes. The Puritans believed you could not live with or even convert monsters. You must destroy them.

31

The Puritans embodied the American desire to destroy monsters. At the same time, the Puritan tendency toward witch-hunting reveals the American tendency to desire the monster, indeed to be titillated by it. Contemporary literary scholar Edward Ingebretsen convincingly argues that the search for witches in the towns of New England should be read as popular entertainment as well as evidence of religious conflict and persecution. Ingebretsen shows that Mather makes use of the term “entertain” frequently when explaining his own efforts to create a narrative of the witch hunts. He uses the same term to describe the effect of the testimony of suspected witches on the Puritan courtrooms that

heard them. Mather described the dark wonders that make up much of his writings as “the chiefe entertainments which my readers do expect and shall receive.”

32

Mather obviously does not use the word “entertain” in the contemporary sense. And yet his conception of “entertainment” bears some relationship to the more modern usage of the term. Mather believed that his dark entertainments warned and admonished, but a delicious thrill accompanied them as well. Mather himself sounds like a carnival barker when he promises frightening spectacles that his readers “do expect and shall receive.” Historian of Salem Marion Starkey, in

The Devil in Massachusetts

, notes that for all of Mather’s righteous chest-thumping over the danger the New England colonies faced from the assaults of Satan, it is hard not to see him “unconsciously submerged in the thrill of being present as a spectator.” He provided his readers the same thrill.

33

This thrill had clear erotic undertones, underscoring the close connection between horror and sexuality that became a persistent thread in American cultural history. The genealogy of the witch in western Europe already included many of the ideas that aroused, in every sense, the Puritan settlements. Folklore taught that any gathering of witches, known as the “witches sabbat,” included orgiastic sex, even sex with Satan and his demons. European demonologists frequently connected the tendency to witchcraft with a propensity toward uncontrolled sexual desire.

34

Such ideas appeared again and again in the New England witch hunts. The trial of indentured servant Mary Johnson not only included accusations that she had used her relationship with Satan to get out of work for her master, but also the assertion that she had flirted, literally, with the devil. Cotton Mather wrote that she had “practiced uncleanness with men and devils.” One of the first women accused of witchcraft in Salem village had a reputation for sexual promiscuity, while male testimony against women accused of witchcraft often included descriptions of them as succubi, appearing at night dressed in flaming red bodices. The witch was not only one of the first monsters of English-speaking America. The witch also became America’s first sexy monster and one who would be punished for her proclivities.

35

The end of the witch trials in 1693 came with numerous criticisms of how the cases had been handled. Petitions on behalf of the accused began to appear in the fall of 1692. In October of that year, Boston merchant Thomas Brattle, a well-traveled member of the scientific Royal Society with an interest in mathematics and astronomy, published an open letter criticizing the courts. He especially critiqued the Puritan judiciary for allowing “spectral evidence,” evidence based on visions, revelations,

and alleged apparitions. Significantly, Brattle did not challenge the idea that supernatural agency had been involved in the trials, only that it had worked by different methods than the Puritan judiciary had supposed. Brattle wrote that the evidence of witches sabbats and apparitions put forward by those who accused (and by those who confessed) represented “the effect of their fancy, deluded and depraved by the Devil.” In Brattle’s mind, to accept such evidence would be tantamount to accepting the testimony of Satan himself. Like many skeptics during this period, Brattle challenged the courts on how they had used the belief in monsters, without questioning the reality of the existence of monsters.

36

Salem did not mark the end of the witch trials in America. Fear of that old black magic remained a crucial part of early American life. Marginalized women and enslaved Africans remained the most common target of the witch hunt. In 1705–1706, a Virginia couple, Luke and Elizabeth Hill, accused Grace Sherwood of witchcraft. Although the Virginia courts at first found little evidence for the charge, the time-honored search for the witch’s teat soon revealed “two things like titts with Severall other Spotts.” Sherwood next underwent the infamous “water test” in which the suspected witch was thrown into water to see if she floated or sank. Sherwood floated and faced reexamination by some “anciente women” who, this time, discovered clearly diabolical “titts on her private parts.” She was subjected to another trial, although the record breaks off at this point, making her fate unclear.

37

Enslaved Africans faced accusations of a special kind of witchcraft known as “conjuration” or, more simply, “sorcery.” The use of black magic against the white master class became a common charge against the instigators of slave rebellions. In 1779 a trial of slave rebels in the territory that would later become the state of Illinois ended with the execution of several slaves for the crimes of “conjure” and “necromancy.”

38

The Puritans clearly had no monopoly on the belief in witchcraft. Even in parts of colonial America without a strong tradition of witch trials, beliefs that supported such trials remained strong. An Anglican missionary in colonial Carolina, Francis Le Jau, complained in a 1707 journal entry that the colonial court had not severely punished “a notorious malefactor, evidently guilty of witchcraft.” While the Puritans pursued their obsession with the most vehemence, the belief in dark powers inhabiting the American landscape remained common throughout the eighteenth century.

39

Puritans found more monsters in their new world than the witch. Although we tend to picture the dour Puritans in their equally dour meetinghouses, taking in Calvinist theology and morality in great

drafts, the actual Puritans lived out at least part of their experience in what David D. Hall has termed “worlds of wonder.” The work of Hall, and of colonial historian Richard Godbeer, has uncovered a variety of magical traditions, astrological beliefs, and conceptions of monstrosity among the Puritans that kept alive older European wonder-lore. Puritan conceptions of original sin, for example, contributed to their interest in abnormal births, often termed as “monstrous births,” that functioned as signs and omens. Spectral, shape-shifting dogs haunted the edges of the Puritan settlements, as did demonic, giant black bears.

40

Predictably, much of the Puritan ministry saw any portents in nature as signs of the New Englanders’ divine mission. The same clergymen, just as predictably, ascribed a diabolical character to any marvel or wonders, that did not fit into their theological paradigm. For Puritan clergy, it came as no surprise to find the forests of New England populated with marvelous creatures. Their new world was surrounded by evil spirits of all kinds, as numerous as “the frogs of Egypt” according to Cotton Mather.

41

Reaction to an alleged sighting of a sea serpent early in the Puritan experiment showcases this attitude. Puritan observers claimed to have encountered sea serpents long before the nineteenth-century sightings in Gloucester harbor. They also more quickly ascribed dark religious meanings to the appearance of the creature off their shores. In 1638 New England settler John Josselyn reported that recent arrivals to the colonies had seen “a sea serpent or a snake.” Nahant native Obadiah Turner described the same creature and worried that “the monster come out of the sea” might be “the old serpent spoken of in holy scripture … whose poison hath run down even unto us, so greatly to our discomfort and ruin.” The monster could be a portent of divine providence or judgment. The only other possible explanation was that it was a creature of Satan.

42