Moon Lander: How We Developed the Apollo Lunar Module (18 page)

Read Moon Lander: How We Developed the Apollo Lunar Module Online

Authors: Thomas J. Kelly

Tags: #Science, #Physics, #Astrophysics, #Technology & Engineering, #History

Prior to the TM-1 review we had given considerable thought to the problem of egress to the lunar surface. To help evaluate possible techniques, Rigsby and Sherman designed an apparatus called the “Peter Pan rig,” a cable-and-pulley device suspended from the mockup room’s overhead traveling crane that counterbalanced five-sixths of a spacesuited subject’s weight. This crudely simulated the gravitational force on the lunar surface, which is one-sixth that of Earth. By supporting the subject from a chest harness, belt, and thigh straps attached to the Peter Pan rig and moving the overhead crane to follow the subject’s movements, we could evaluate the feasibility and relative difficulty of performing various maneuvers on the Moon’s surface.

We evaluated a number of means of getting onto the lunar surface and back into the LM. We thought it could be done by using a knotted rope to climb up and down from the LM and a block and tackle to lower and raise scientific

equipment and sample containers. This required a platform on top of the landing-gear support strut in front of the forward hatch upon which the astronaut could stand before descending the rope. This platform was nicknamed the “front porch.” Stephenson and Harms tried this maneuver in spacesuits a few days before the review. They found it slow and strenuous but feasible. Objective evaluation was difficult because it took time and practice to adapt to the Peter Pan rig and attain proficiency in moving about with it. We definitely needed NASA’s opinion.

During the formal mockup review eighty NASA engineers and astronauts inspected TM-1 and wrote more than one hundred chits, fifty-two of which were presented to the review board. Improvements were made in the feel and positioning of flight controls, equipment stowage within the cabin, the positioning of circuit breakers switches, and other crew compartment internal details. After a full day of evaluation by Ed White, Grumman’s proposed use of rope, block, and tackle for lunar surface egress was declared unacceptable. White found it too difficult and unnecessarily hazardous for what should be a routine activity. We agreed to devise alternate schemes and to conduct evaluation sessions on the Peter Pan rig with Ed White and others, aiming at a decision review on TM-1 in May 1964. The cabin lighting was also considered in need of further improvement, especially the electroluminescent panels. A lighting review was scheduled to take place in May (at the same time as the egress evaluation) with the astronauts.

The issue of whether LM needed docking capability at the front hatch in addition to the overhead hatch was examined by the TM-1 review team. Forward docking was a hangover from Grumman’s LM proposal but was no longer considered necessary for redundancy. The remaining argument in its favor was LM pilot visibility during the close docking approach maneuver. LM would be the active vehicle during rendezvous maneuvers and approach to the CSM. The LM pilot would fly this segment from his normal flight position, standing in his flight station and looking at the CSM out the front window. If LM could dock with its front hatch upon return from the Moon, the LM pilot would not change his flight position when he handed off active maneuvering command to the CM pilot, who would capture and dock the LM.

I thought it desirable to eliminate the docking requirement from the forward hatch for several reasons. It would save weight by eliminating the forward docking tunnel and docking impact loads on the front face structure, and it would give us more design flexibility with the forward hatch if we needed it to be larger or other than circular. We could probably simplify the hatch-locking mechanism as well. Both Grumman and NASA engineers had suggested that a small rectangular window be placed in the cabin ceiling, directly over the LM pilot’s head, to provide visibility of the CM during the close docking approach maneuver.

During the TM-1 review, White, Conrad, and others evaluated this possibility

They tried bending their heads backward to look out the overhead window while wearing spacesuits and restrained at the normal flight station. They noted the difficulty of using the LM controls in this position and of switching eye contact back and forth between the instrument panel and the overhead window. They concluded that the position was somewhat awkward but not unworkable, and it would probably be easier at zero gravity. The astronauts recommended and the board approved a month of study and simulation at Houston before making a final decision, but the overhead docking scheme appeared promising.

TM-1 had most of the electronic equipment mounted externally on the ascent stage behind the pressurized crew compartment. The electronic “black boxes” were mounted on vertical racks facing each other, with a ladder up the side aiding access. During the review a simpler concept of mounting the boxes lengthwise on vertical rails in a single array facing aft was discussed with NASA and accepted for further study.

Several other TM-1 design issues were reviewed with NASA, including the stowage of scientific equipment in the descent-stage bays, the placement of antennas and of handholds to aid crew mobility on both stages, and ground clearance of the descent engine bell. The review stimulated ideas from NASA and Grumman on means of resolving these and other issues. We also used TM-1 during discussions with LM Manufacturing on possible design and manufacturing approaches to building the front face of the crew compartment. It was a flat, pressurized, sheet-metal structure with complex geometry and angles and major penetrations for the forward hatch and windows. I favored welded construction in order to save weight and provide a leak-tight compartment, but the geometry appeared to preclude that solution.

The TM-1 mockup review ended optimistically. Many crew compartment design details had been resolved and others placed on a path to resolution, often using TM-1 as the evaluation test article. Over the next two months, White and Conrad worked on TM-1 and the Peter Pan rig, and with Grumman’s Crew Systems, Structural Design, and Mechanical Design engineers came up with a much better concept for egress to the lunar surface. They enlarged and added handrails to the front porch platform and fitted a ladder to the forward landing-gear strut. The astronaut descended to the surface by crawling backward out of the forward hatch, then across the platform and down the ladder while facing it. Returning from the surface he faced the ladder again, climbed up it onto the platform, and crawled forward through the hatch. He could carry a full rock sample container with one hand (at one-sixth G), place it on the front porch ahead of him, and push it in through the hatch. The whole surface egress procedure was made easier, safer, and more intuitive. This design was approved at the interim TM-1 review in May 1964, as were improved cabin lighting provisions and electroluminescent panels, the latter being enthusiastically endorsed by Pete Conrad. The Houston studies

of overhead docking also were positive, and the requirement for docking with the forward LM hatch was deleted. Further work by LM Engineering and Manufacturing resulted in the selection of a hybrid manufacturing approach to the front face structure, a combination of welding and riveted construction. With these key decisions we were ready to firm up the LM design configuration and basic operational details with the last planned LM mockup.

M-5

Rathke and I decided to make M-5 an accurate engineering and manufacturing aid that we could use for fit checks, configuration and operations studies, and development of manufacturing techniques. Most of it was metal, with parts made from accurately dimensioned engineering drawings, not just sketches. M-5 was a shakedown for the LM project’s drawing release and configuration control systems and provided the newly formed LM Manufacturing Department’s first challenge. From our subcontractors and suppliers we obtained accurate mockups of equipment and components, including the rocket engines, reaction control thrusters, environmental control assemblies, tanks, antennas, and flight displays and controls. In some places we were able to install prototype flight hardware, as with the crew station controls, supports, and restraints. We installed flight-type electrical wiring harnesses, connectors, and fluid system plumbing and components. These installations closely simulated the form and fit of flight hardware but were nonfunctional. The external surfaces of the ascent and descent stages were covered with thin, shiny aluminum sheets, simulating the micrometeorite shields that would cover the flight LMs. In its gleaming metallic shell, M-5 looked like an exotic space creature. Did we create this strange apparition or was it built on the Moon by little green men? This LM seemed like it would be at home on the Moon.

More than four hundred Grumman engineering drawings were required to define M-5, plus many more from our subcontractors. In mid-1964 LM Engineering had its first struggle to meet a schedule of drawing releases to Manufacturing; a foretaste of what would soon become our major preoccupation. Bob Carbee personally led the engineering work on M-5, pushing and coordinating the drawing outputs from the LM design groups. The last two weeks before the review Engineering and Manufacturing worked around the clock in two shifts, seven days a week to finish M-5 on time.

There was an embarrassing glitch about a week before the review. When M-5 was moved into position on the mockup room floor, it was evident that we would not be able to demonstrate the deployment of the forward landing-gear strut from stowed to extended position because of lack of ground clearance. During deployment the landing gear extended below the floor if M-5 was supported on the floor by its own landing-gear legs. Raising M-5 up on

pedestals under its feet would provide the necessary clearance for the deployment demonstration but would leave M-5 two and a half feet above the mockup room floor, which was not acceptable for conducting lunar egress exercises. We shamefacedly accepted the solution of breaking up the concrete floor and digging a trench through which the front landing gear could sweep during deployment. Engineering took a lot of flak for not foreseeing that problem earlier.

The review commenced on 6 October 1964, with more than one hundred NASA astronauts and engineers in attendance, and continued through 8 October, when the reviewers were augmented by MSC director Bob Gilruth and MSFC director Wernher von Braun and virtually all the Apollo program leadership from Houston. NASA was pleased with the quality of M-5 and its extensive detail, and they closely examined and evaluated each area. Von Braun was very enthusiastic. He climbed up the ladder and through the front hatch into the cabin and inspected the interior. Upon exiting, he called excitedly to a Marshall colleague from M-5’s front porch, “You’ve got to go up there. Go in there; it’s great!”

1

Astronaut Roger Chaffee donned a spacesuit and mockup backpack and practiced entering and exiting M-5 from the surface. He had difficulty squeezing through the front hatch due to repeated hangups with the bulky backpack. He insisted that I watch the maneuver, together with Carbee, Rigsby, and Harms, and afterward declared that the circular shape of the front hatch was wrong. What was needed was a rectangular hatch, somewhat higher than wide, to match the squarish form factor of the backpack. We were convinced by his demonstration and approved the chit he wrote when it came before the review board. Because the front hatch no longer was required to perform docking, the circular shape was not necessary.

The M-5 mockup review board convened with Owen Maynard as chairman and Carbee and I representing Grumman. We sat at a large conference table on the mockup room floor in front of M-5, facing the audience. Microphones on the table and speakers amplified our voices, and we and the chit presenters used a lectern and slides projected onto a large portable screen to address each item under discussion. More than 250 people were present, filling every row of chairs and spilling over into standing room along the walls. Gilruth, von Braun, several astronauts, and other high-ranking NASA officials attended and followed the proceedings with interest, despite the difficulty seeing and hearing the presentations in the crowded hall. A total of 148 changes were proposed, and the board approved 120 of them. Most of the changes were minor and none forced major redesign; even the change in forward hatch shape was readily accommodated.

2

Max Faget was very impressed with our mockup, declaring it was what an engineering mockup should be like. He said North American’s mockup was mainly a marketing prop while Grumman’s was an engineering design tool.

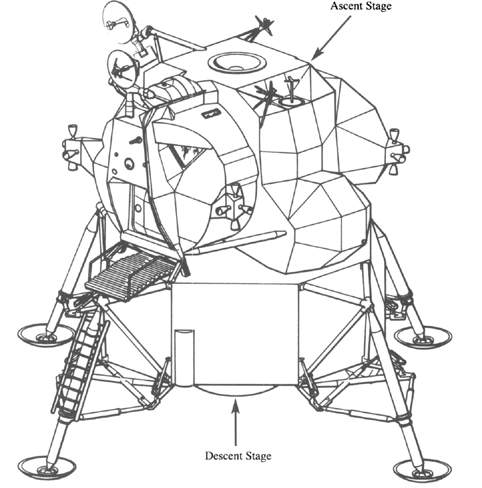

The final lunar module design. (Courtesy Northrop/Grumman Corporation) (

Illustration credit 6.1

)

The M-5 review provided Grumman management a great opportunity to exchange ideas with our NASA counterparts and to gain insight into their concerns and opinions. Gavin, Mullaney, Rathke, and I all benefited from discussions with Max Faget, Chris Kraft, and astronauts Chaffee, White, and Conrad. Faget was a gifted, intuitive aerospace designer. He made numerous informal suggestions for further improvement or simplifications of designs that were represented on M-5. He was very pleased with the ladder and front porch for lunar egress but, along with Chaffee, recommended we make the hatch bigger and rectangular.