Moses and Akhenaten (10 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

In this second example the word used is again

b-y-t Phar'a.

However, in the Book of Exodus, where we have the story of Pharaoh's daughter going down to bathe, finding the Hebrew child in the rushes and later adopting him, the

y

is absent and we have simply

b-t Phar'a.

My suspicion was that during the ninth century

BC,

the early stages of written Hebrew when the Old Testament was given permanent form, all three words had been written in this way, referring in each instance to the âhouse of Pharaoh', the reigning queen, and the

y

in the two Genesis references had been added later, as written Hebrew developed, because the scribe did not understand the special Egyptian usage of the word âhouse'. This, while not easy to establish, proved to be the case.

The Hebrew Masoretic text we have now goes back only to around the tenth century

AD

and could not throw any light on the matter. Nor could sections of the Old Testament found in the caves of Qumran, near the Dead Sea, some of which belong to the second century

BC.

Confirmation was eventually provided by the Moabite Stone. This black basalt inscribed stone was left by Mesha, King of Moab, at Dhiban (biblical Dibon, to the east of the Dead Sea) to commemorate his revolt against Israel and his subsequent rebuilding of many important towns (II Kings, 3:4â5). The stone was found by the Revd F. Klein, a German missionary working with the Church Missionary Society, on 19 August 1868 and is now in the Louvre in Paris. The inscription refers to the triumph of âMesha, ben Chemosh, King of Moab', whose father reigned over Moab for thirty years. He tells how he (Mesha) threw off the yoke of Israel and honoured his god, Chemosh.

2

According to the American archaeologist James B. Pritchard, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania: âThe date of the Mesha Stone is fixed roughly by the reference to Mesha, King of Moab, in II Kings, 3:4, after 849

BC.

However, since the contents of the stela point to a date toward the end of the king's reign, it seems probable that it should be placed between 840 and 820, perhaps about 830

BC

in round numbers.'

3

The text reads: âI [am] Mesha, son of Chemosh ⦠King of Moab ⦠I said to all the people: “Let each of you make a cistern for himself in his house.”'

The inscription, written in the Semitic language used for writing at the time by the Jews of Israel, confirms that the word for âhouse' was then written simply

b-t,

without the insertion of ây' and was the same as the word for daughter. This is also true of the way it was written in the Phoenician language.

4

When âhouse' and âdaughter' were written identically there was no cause to differentiate between them. The situation changed when development of the Hebrew language made it possible to alter the spelling slightly to give two different words. The scribes then found themselves in a dilemma, based on their ignorance of the fact the âhouse' had the Egyptian meaning âwife'. It now becomes clear what happened. If the word simply meant âhouse' or âhousehold', it made sense that Joseph approached the house of Pharaoh on the subject of his father's funeral and that his weeping could be heard in the king's house, but it made no sense at all to suggest that the whole of the king's household had come âdown to wash herself at the river' (Exodus, 2:5) or had become the mother to the child. The scribe therefore decided in the Exodus reference to retain the alternative meaning of âdaughter' whereas it, too, should have been changed to âhouse', signifying the wife of Pharaoh, his queen.

There is a similar case of semantic confusion, cited by Professor Cassuto, with the source again the Book of Exodus: âAnd Moses took his wife and sons, and set them upon an ass, and he returned to the land of Egypt â¦' (Exodus, 4:20). Professor Cassuto remarks: âThe plural â sons â is somewhat difficult, for till now only one son (Gershom) had been mentioned (Exodus, 2:22), and below, in Exodus, 4:25, we find “her son”, in the singular, as though Moses and Zipporah had just one son. Possibly the ancient spelling here was

b n h,

which could be read as either singular or plural, and the singular was actually intended; when, however, the scribes introduced the present spelling they wrote

ba na w

[his sons] (the Septuagint [the Greek version of the Old Testament], too, has the plural) because they thought the two sons spoken of (later) in Exodus, 18:3â4 were already born.'

5

The royal mother of Moses was therefore the Queen of Egypt. But which queen? As we saw earlier (

Chapter Two

), Manetho, the third century

BC

historian, identified the reign of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye â while son of Habu was still alive, some time before the king's Year 34 â as the right time for the religious rebellion that led to the persecution of Akhenaten's followers, and Redford has made the point that it is not built simply on popular tales and traditions of Manetho's time, but on old traditions, passed on orally at first, then set down in writing, that he found in his temple library.

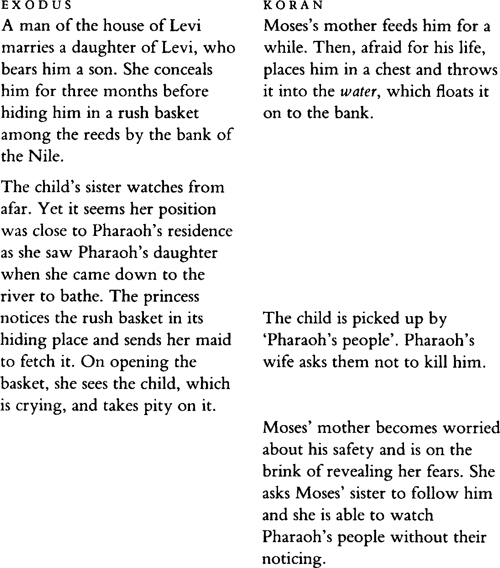

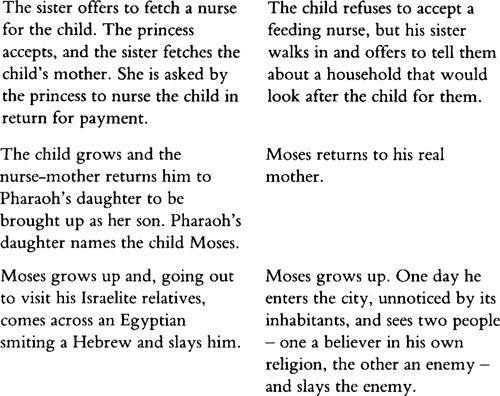

If we compare in greater detail the Koran account (Sura XX:38â40 and Sura XXVIII:7â15) with the biblical account (Exodus, 2:1â12) of Moses' birth and eventual flight after the slaying incident, we find the stories are fundamentally the same, yet also contain some interesting differences:

The significant differences in these accounts are:

⢠The Koran story does not give us the names of Moses' parents;

⢠While the biblical story tells us that the rush basket was left by the river, the Koran refers to âthe water', which could be a lake joined to the river;

⢠While Pharaoh's daughter (or wife, as we saw before) is said by the Bible to have been the child's rescuer, it was âPharaoh's people' according to the Koran;

⢠The biblical version says that Moses' sister watches events while the child is in its basket, hidden in the reeds outside Pharaoh's palace, but this is not the case in the Koran; there it is only after the child was in the possession of âPharaoh's people' that his sister is asked by the mother, who must have been in the vicinity at the time, to follow after him, which she does secretly, indicating that this incident must have taken place in the palace itself;

⢠Pharaoh's wife, who, according to the Koran, had nothing to do with the child until he had fallen into the hands of âPharaoh's people', then intervened to prevent them â probably the guards â from killing him;

⢠Once the child was in the custody of âPharaoh's people', we are told in the Koran that the child's mother became worried about what might happen to him. Why would she be worried unless she was in a position to know what was going on inside the palace?

⢠The mother, according to the Koran, was about to reveal her hidden fears for the safety of the child. This is the strongest indication so far that the child's mother and Pharaoh's wife were one and the same person. After her intervention to prevent him from being killed, he was taken away from her. She then became so worried that she was about to reveal that she was the mother of the baby, but instead she sent the sister to find out what was happening inside the palace;

⢠Rather than killing the child, Moses' sister, according to the Koran, succeeded in persuading âPharaoh's people' to place him in the care of a family that would look after him. Here there is another crucial point. Where the Bible indicates that the child was later returned to Pharaoh's daughter to be brought up by her, the Koran makes it clear that this event was the actual return of Moses to his real mother;

⢠The Koran story states that Moses went out of the palace and âentered the city', thus implying that the palace was not far from the city, and use of the word âunnoticed' here can only mean that he was neither dressed in princely attire at the time, nor was he attended by guards;

⢠While the biblical account of the slaying incident describes the two men who were fighting as an Egyptian and a Hebrew, the Koran version of the story makes them a follower of Moses' religion and an enemy, implying that at this stage, even before his flight to Sinai, Moses had a different religion that had followers as well as enemies.

6

THE RIGHTFUL SON AND HEIR

I

F

we assume for the moment what is as yet far from proved â that Moses and Akhenaten were the same person â it is possible to assemble a brief outline of the historical facts behind the varied, and at times extravagant, accounts of the life of the greatest Jewish hero that we find in the Old Testament and other holy books, and to offer an explanation of why the world should have remembered him by the name of Moses.

Moses, the second son of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, was born, I believe, at the frontier fortified city of Zarw, probably in 1394

BC

(see also

Chapter Eleven

). His elder brother, Tuthmosis, had already disappeared mysteriously, and, in view of the threats that were about to be made to the life of Moses, it seems more than likely that the disappearance of Tuthmosis was not the result of natural causes. The reason for the king's hostility to the young princes was the fact that Tiye, their mother, was not the legitimate heiress. She could therefore not be accepted as the consort of the State god Amun.

Furthermore, as she herself was of mixed Egyptian-Israelite blood, her children would not, by Egyptian custom, be regarded as heirs to the throne. If her son acceded to the throne, this would be regarded as forming a new dynasty of non-Egyptian, non-Amunite, part-Israelite kings over Egypt. This is exactly the light in which the Amunite priests and nobles of Egypt, the watchdogs of old traditions, regarded Akhenaten. It was not he who first rejected the position of son of Amun: it was they, the Amunists, who refused to accept him as the legitimate heir to the throne.

Consequently, the king, motivated by the possible threat to the dynasty and confrontation with the priesthood, instructed the midwives to kill Tiye's child in secrecy if it proved to be a boy. The Talmud story confirms that it was the survival of Moses that Pharaoh wanted to prevent, because, once he knew that Moses had been born and survived, his attempt to kill all the male Israelite children at birth was abandoned: âAfter Moses was placed in the Nile, they [Pharaoh's astrologers] told Pharaoh that the redeemer had already been cast into the water, whereupon Pharaoh rescinded his decree that the male children should be put to death. Not only were all the future children saved, but even the ⦠children [who had already been] cast into the Nile with Moses.'

1

Zarw was largely surrounded by lakes and a branch of the Nile. On learning â perhaps from the midwives â that her son's life was in danger, Tiye sent Moses by water to the safe-keeping of her Israelite relations at nearby Goshen. Yet the biblical story makes it clear that the king was still afraid of Moses. Why should the mighty Pharaoh fear Moses if he was simply a child of the despised Asiatic shepherds? In those circumstances, how could he have posed a threat to the Dynasty?

Moses spent most of his youth in the Eastern Delta where he absorbed the traditional Israelite beliefs in a God without an image. It was not until he was a grown boy that he was finally allowed to take up residence at Thebes, the capital city in Upper Egypt and the principal centre of worship of the State god, Amun. By this time the health of his father had begun to deteriorate and Tiye's power had increased correspondingly. In order to ensure her son's ultimate inheritance of the throne, she therefore arranged for him to marry his half-sister Nefertiti â the daughter of Amenhotep III by

his

sister, Sitamun, the legitimate heiress â and to be appointed his father's coregent, with special emphasis on Nefertiti's role in order to placate the priests and nobles.

Moses, whose religious ideas were already well developed, offended the Amunite priesthood from the start of the coregency by building temples to his monotheistic God, the Aten, at Karnak and Luxor. In a climate becoming increasingly hostile, Tiye eventually persuaded him to leave Thebes and found a new capital for himself at Tell el-Amarna, some 200 miles to the north, roughly halfway between Thebes and the Eastern Delta. Moses named his new city Akhetaten â the city of the horizon of the Aten â in honour of his new God.