Moses and Akhenaten (9 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

The Bible does not state directly that the pursuing Pharaoh died in the waters although this is implied:

And the waters returned, and covered the chariots, and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them; there remained not so much as one of them. (Exodus, 14:28)

The Koran, however, makes it clear that the pursuing Pharaoh, too, was drowned:

We took the Children

Of Israel across the sea:

Pharaoh and his hosts followed them

In insolence and spite.

At length, when overwhelmed

With the flood, he said:

âI believe that there is no god

Except Him Whom the Children

Of Israel believe in: â¦'

(It was said to him) â¦

âThis day shall We save thee

9

In thy body, that thou

Mayest be a Sign to those

Who come after thee!

But verily, many among mankind

Are heedless of Our Signs!'(Sura X:90â92)

10

Ramses I is known to have ruled for less than two years. The biblical account of this part of the Exodus story cannot therefore agree more precisely than it does with what we know of the history of Ancient Egypt at this time. If Ramses I was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, Horemheb was the Pharaoh of the Oppression. But how long had the Israelites been in Egypt when these events took place?

5

SOJOURN â AND THE MOTHER OF MOSES

C

ONTRADICTORY

accounts in the Old Testament make it difficult to arrive at the precise date when the Patriarch Joseph and the Israelites arrived in Egypt. As we saw earlier, we are offered a choice of three periods for the Sojourn â 430 years, 400 years and four generations. In

Stranger in the Valley of the Kings

I argued that the figure of 430 years was wrongly arrived at by the biblical editor in the following way: firstly, he added up the four generations named in the Old Testament account of the Descent into Egypt as if each new generation were born on the very day that his father died, having lived for more than a century:

Then he deducted the years (fifty-seven) that Levi lived before the Descent â according to the Talmud he lived eighty years after the Descent and died at the age of 137 â plus the forty years Moses is said to have lived after the Exodus. This left him with his total of 430 years. This method of computation is obviously unsound, and I have since been pleased to find that many biblical scholars agree with my view that the figure of 430 years for the Sojourn is not to be taken literally â a variety of explanations are put forward â while it is, surprisingly, the majority of Egyptologists who appear to look upon it as a sacred figure not to be challenged.

One eminent biblical scholar who has commented on the length of the sojourn is the late Umberto Cassuto, formerly Professor of Biblical Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who wrote: â⦠the numbers given in the Torah are mostly round or symbolic figures, and their purpose is to teach us something by their harmonious character ⦠these numbers are based on the sexagesimal system, which occupied in the ancient East a place similar to that of the decimal system in our days.

âThe chronological unit in this system was a period of sixty years, which the Babylonians called a

Å¡Å«Å¡

.

One

Å¡Å«Å¡

consisted of sixty years and two

Å¡Å«Å¡

of a hundred and twenty years â a phrase that is used by Jews to this day. In order to convey that a given thing continued for a very long time, or comprised a large number of units, a round figure signifying a big amount according to the sexagesimal system was employed, for example, 600, 6000, 600,000 or 300, 3000 or 300,000 or 120, 360, 1200, 3600 and so forth. I further demonstrated there that, if it was desired to indicate a still larger amount, these figures were supplemented by seven or a multiple of seven. The number 127, for instance (Genesis, 23:1), was based on this system.'

1

Elsewhere Professor Cassuto makes the point that the figure forty, found frequently in the Bible, is similarly used as a kind of shorthand for a period of time and is not to be taken literally.

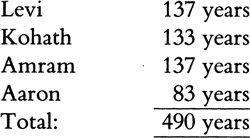

He then goes on to try to harmonize the two Israelite traditions â that the Sojourn lasted 430 years (six times sixty, plus seventy) and four generations. He cites as his four generations Levi, Kohath, Amram and Aaron, who is said to have been the brother of Moses, and adds together the years they are given in the Old Testament. This approach is permissible, he argues, because

a) Each generation endured the burden of exile throughout the times of its exile, and its distress was not diminished by the fact that it was shared by another generation during a certain portion of that period; hence in computing the total length of exile suffered, one is justified to some extent in reckoning the ordeal of each generation in its entirety,

b) A similar and parallel system was used in the chronological calculations of the Mesopotamians. In the Sumerian King List, dynasties that were partly coeval, one reigning in one city and the other elsewhere, are recorded consecutively, and are reckoned as if they ruled successively. Consequently, if we add up the years that these dynasties reigned, we shall arrive at a total that is actually the sum of the periods of their kingship, although it will exceed the time that elapsed from the commencement of the first dynasty to the end of the last.

Professor Cassuto then proceeds to make the following calculation:

Here he points out that âupon deducting from [this total] (in order to allow for the time that Levi and Kohath dwelt in the land of Canaan before they emigrated to Egypt) one unit of time, to wit, sixty years, we obtain exactly a period of 430 years, which is the number recorded in Exodus, 12:40.' The 430 years are thus the total years of the four generations and are not to be taken as representing the period of time that elapsed between the Israelites' arrival in Egypt and their departure.

Only two Hebrew generations, Amram and Moses, were actually born in Egypt â Kohath arrived with his father, Levi (Genesis, 46:11) â and, in working backwards from the reign of Ramses I, the Pharaoh of the Exodus, to try to establish the time of the Descent, calculation depends upon the age young Hebrew boys married at the time and had their first child. It seems reasonable to suggest that the period in which the Descent took place should be sought within the range of some fifty to eighty years earlier than the Exodus.

It may be helpful at this point to show how this chronology accords with that arrived at, through a different approach, in

Stranger in the Valley of the Kings,

which sought to establish that Joseph the Patriarch was the same person as Yuya â vizier, Master of the Horse and Deputy of the King in the Chariotry to both Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III â whose mummy, despite the fact that he did not appear to be of royal blood, was found in the Valley of the Kings in the early years of this century.

There I argued that Joseph/Yuya arrived in Egypt as a slave during the reign of Amenhotep II and, after his spell of service in the household of Potiphar, captain of Pharaoh's guard, followed by his imprisonment on a false charge of adultery, was eventually released and appointed vizier by Tuthmosis IV, who was a dreamer like Joseph himself. Once in office he brought the tribe of Israel down from Canaan to join him in Egypt where they settled at Goshen in the Eastern Delta.

According to the Book of Genesis, the total number of Israelites who settled in Egypt was seventy. Yet we are provided with only sixty-nine names â sixty-six who made the Descent, plus Joseph and his two sons, Manasseh (Egyptian, Anen) and Ephraim (Egyptian, Aye). It is a reasonable deduction that the seventieth member of the tribe of Israel was also already in Egypt. I believe that she was a daughter of Joseph, Tiye. Why would her name be omitted? It may be because it is common in the Bible not to mention the names of women unless they are particularly important to the story that is being told. Alternatively, in the lingering bitterness surrounding the Exodus, her name may have been suppressed centuries later by the biblical editor in order to conceal this historical link between the royal house of Egypt and the tribe of Israel which would show that Moses, their greatest leader, was of mixed Egyptian-Israelite origins.

The positions held by Joseph and his wife, who was the king's âornament' (

khrt nsw

), a post which might be said to combine the duties of a modern butler and lady-in-waiting, meant that both had to live in the royal residence. It was thus that the young prince, Amenhotep, grew up with, and fell in love with, Tiye. Then, after his father's early death when the young prince was about twelve, he married his sister, Sitamun, who was most probably an infant, in order to inherit the throne, but soon afterwards also married Tiye and made her, rather than Sitamun, his Great Royal Wife (queen). The evidence that Tiye was about eight at the time of the wedding indicates that Tuthmosis IV must have appointed Joseph to his various positions, including vizier, early in his short eight-year reign.

Tiye, we know, was the mother of Akhenaten â but she must also have been the mother of Moses if he and Akhenaten were the same person.

While the second chapter of the Book of Exodus describes the daughter of Pharaoh as being the royal mother of Moses, the Koran claims that the mother was the queen, Pharaoh's wife. It is strange that, as both holy books must have had the same origin, whether God's inspiration or a literary source, they should not agree in this important matter, particularly when Egyptian custom would not have allowed an unmarried princess to adopt a child. How then has the variation arisen?

There are two sources for the misunderstanding. In the first place, the scribe who wrote down the Book of Exodus was faced with two traditions â that the mother of Moses was an Israelite and that she was

b-t Phar'a,

literally âthe house of Pharaoh'. Unaware, as she had already been omitted from the Joseph story in the Book of Genesis, that Joseph had a daughter named Tiye, who became Pharaoh's wife, he resolved this initial difficulty by creating two mothers, one Hebrew, who gave birth to Moses, and one royal, who adopted him and brought him up as her son. That he chose to identify this adoptive mother as a princess rather than a queen has a philological explanation.

The word for âdaughter' and the word for âhouse' were written identically

b-t

in early Hebrew and open to misconstruction by anyone not familiar with Egyptian usage. To an Egyptian the word âhouse' was also used â and, indeed, still is â to signify a wife: to a Hebrew it meant either âhouse' in the sense of a building or âhousehold'. Later, both Hebrew and the language of Ancient Egypt, which had no written vowels, began to use some consonants like

y

to indicate long vowels. Thus, for example, we find a slightly different spelling of

b-t Phar'a

in the Book of Genesis account of events when Jacob, the father of Joseph, died. Joseph, who wanted permission to take him back to Canaan for burial, did not speak to the king directly but to

b-y-t Phar'a,

the Hebrew word signifying âthe house of Pharaoh': âAnd when the days of his mourning were past, Joseph spake unto the house of Pharaoh, saying, If now I have found grace in your eyes, speak, I pray you, in the ears of Pharaoh â¦' (Genesis, 50:4). âPharaoh' itself means literally âthe great house'. Thus

b-y-t Phar'a

signifies the âhouse of the great house', which in the Egyptian sense would mean the queen, whom in this case I regard as Joseph's own daughter, Tiye, whose intercession he sought in the matter of his father's burial.

There is an example of similar usage earlier in the Book of Genesis when the brothers who had earlier sold Joseph into slavery made their second trip to Egypt at a time of famine. On this occasion Joseph revealed his true identity and was so moved that he âwept aloud: and the Egyptians and the house of Pharaoh heard' (Genesis, 45:2). This has been construed as meaning that Joseph's weeping was so loud that it was audible in the royal palace, but I interpret it as meaning that the queen, his daughter, heard the news of his brothers' arrival.