Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (26 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

“Man, you know I believe in my religion,” Ali said, unaware that the son of his spiritual leader was hoping he would accept the deal. “My religion says I’m not supposed to get in any wars and fight. I don’t want any deals. I don’t plan to fight nobody that hasn’t done nothing to me, and I’m not going in any damn service.”

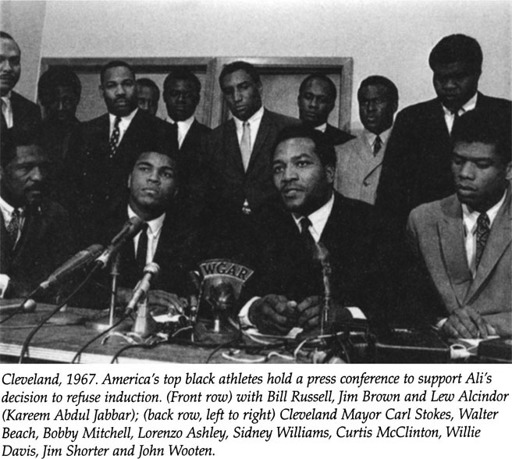

Now, surrounded by the group of famous athletes, Ali told them roughly the same thing. “I’m doing what I have to do,” he said. “I appreciate you fellows wanting to help and your friendship. But I have had the best legal minds in the country working for me, and they have shown me all the options and alternatives I could use if I wanted to go in. Things like going in to be an ambulance driver, or a chaplain, or a truck driver. Or joining and saying I would not kill. I could do any of these things, or I can go to jail. Well, I

know

what I must do. My fate is in the hands of Allah, and Allah will take care of me. If I walk out of this room and get killed today, it will be Allah’s doing and I will accept it. I’m not worried. In my first teachings I was told we would all be tested by Allah. This may be my test.” Then he launched into one of his trademark sermons about the Nation of Islam, the mothership, and Elijah Muhammad. “He was such a dazzling speaker, he damn near converted a few in that room,” Brown recalled. Each left the room convinced of Ali’s sincerity.

Bill Russell later wrote about the meeting for

Sports Illustrated,

revealing that he envied Ali’s absolute and sincere faith. “One of the great misconceptions about Ali is that he is dumb and has fallen into the wrong hands and does not know what he is doing,” he wrote. “On the contrary, he has one of the quickest minds I have ever known. At the meeting in Cleveland, all of us found out thoroughly that he knew a great deal more about the situation than we did. If he were being led blindfolded by the Muslims, I doubt very much that he would be taking the stand he is. What good will he do the Muslims in jail? Right now he is the best recruiter they have.”

Ali’s longtime friend Lloyd Wells lived in Houston and recalls the boxer’s reaction to all the pressure to accept a deal and fight exhibitions.

“He could have easily been like Joe Louis and had an easy time in the army. They promised him he wouldn’t have to fight,” Wells says. “But he never considered it for a moment. He kept saying, ‘I’d be just as guilty as the ones who did.’”

As Ali was being indicted in Houston, the British philosopher Bertrand Russell had convened an International War Crimes Tribunal in Stockholm to hear evidence on the American government’s conduct in the Vietnam War and “to prevent the crime of silence.” Russell had followed Ali’s draft case quite closely and had recently sent him a letter supporting his stand:

In the coming months there is no doubt that the men who rule Washington will try to damage you in every way open to them, but I am sure you know that you spoke for your people and for the oppressed everywhere in the courageous defiance of American power. They will try to break you because you are a symbol of a force they are unable to destroy, namely, the aroused consciousness of a whole people determined no longer to be butchered and debased with fear and oppression. You have my wholehearted support.

The principled stands of Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali were at least partly responsible for a perceptible shift in black American attitudes toward the war. At the Stockholm tribunal, the African-American novelist James Baldwin expanded on their message: “I speak as an American Negro. I challenge anyone alive to tell me why any black American should go into those jungles to kill people who are not white and who have never done him any harm, in defense of a people who have made that foreign jungle, or any jungle anywhere in the world, a more desirable jungle than that in which he was born, and to which, supposing that he lives, he will inevitably return.”

As black and white protest against the war stepped up, a disproportionately large number of high-profile protesters were, it appeared, being inducted into the Army, which was supposed to rely on a random lottery to select its draftees. Within a year of its decision to turn its efforts to protesting the Vietnam War, SNCCs ranks rapidly dwindled as its leaders were drafted one after another. In the three months preceding Alfs induction, sixteen members of the organization were called into the armed forces—a suspiciously high rate to many onlookers. A month before Ali’s induction, a SNCC field secretary named Cleveland Sellers had been ordered to report for induction at the Atlanta Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station. When he arrived, three Counterintelligence Corps agents took him into a room to question him. He later denounced his interrogation as “intimidation” and charged the government with “a conspiracy to induct the whole SNCC organization.” After the ACLU took his case, it was revealed that Sellers’s draft board files contained references to his SNCC employmerit, an FBI agent’s visit to the draft board, and an interesting observation by the psychiatrist who had interviewed him at his physical examination, describing him as a “semiprofessional race agitator.”

Cases like Sellers’s were fuelling suspicions that the draft system was being used to target war protesters. Comments from some prominent Washington politicians did little to dampen such speculation. The second highest ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee, F. Edward Hebert, had recently urged his congressional colleagues to “forget the First Amendment.” Agreeing with Hebert, the committee chairperson L. Mendel Rivers urged the speeding up of the prosecution of draft cases and bringing charges against the “Carmichaels and Kings.” For some time, many had speculated that Ali’s suspicious reclassification—the result of a lowering of standards by the Selective Service—was a political act. Without proof, however, it was impossible to make this case stick.

Thirty years later, however, former Attorney General Ramsey Clark reveals a remarkable feud he was engaged in around the time of the Ali prosecution with the head of the Selective Service, General Lewis Hershey. “Hershey wanted to accelerate the inductions of anti-war protesters and I thought that violated the Constitution because it went against the First Amendment,” recalls Clark, who served as attorney general in the Johnson Administration from 1966 to 1969. “As Director of the Selective Service, he had a lot of power in this area, of course. Hershey wanted to use the system to crush the protests. I was personally opposed to the war right from the beginning so needless to say I wasn’t very sympathetic to his aims. I remember I opposed him all the way on this but the White House didn’t want to get directly involved. They told us to sit in a room together and work it out. I could have resigned to express my opposition but if I had done that, I’m convinced there would have been mass targeting of young protesters on a much larger scale. My conscience couldn’t allow that to happen.”

As attorney general, Clark ended up personally approving Ali’s prosecution, an unusual role for the head of the Justice Department. He says his feud with Hershey was partly responsible.

“I had a policy of not getting involved in individual cases but I ended up looking at the Ali case because of all the controversy over the draft issues. I was always a strong supporter of the right to conscientious objection. I enlisted in the Marines during the Korean War but some of the best people I knew were conscientious objectors. Thoreau had always been a hero of mine, I had read his essay on civil disobedience and I always admired his statement,’ I was not born to be forced.’

“Here I was the Attorney General of the United States and the Ali case was going down. It presented a real conflict. Although I supported the right to conscientious objection, I took a look at his case and realized there was not an objection to war per se but rather this war in particular. To me, it wasn’t moral resistance, it was a political choice. Although I respected his choice, I didn’t think the law permitted this form of objection. Society would break down if each individual was permitted to choose which laws they obeyed based on their political views.”

Ironically, Ramsey Clark now represents Ali as a private attorney.

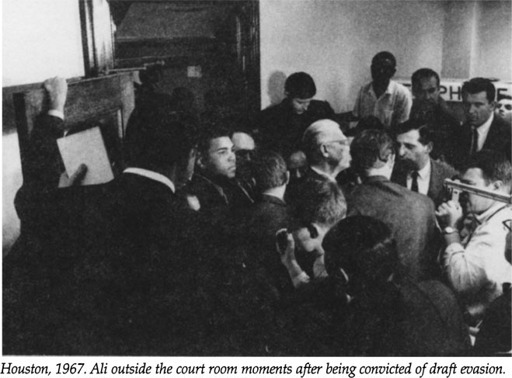

On June 20, Ali appeared in federal court to face trial for refusing induction. Carl Walker, a black assistant U.S. Attorney, prosecuted the case for the government.

“I would say it became a political case. I think politics got into it more than anything else,” Walker later claimed. “Back in those days, I was responsible for prosecuting all of what we called the’draft evaders’….Muhammad had joined the Muslims, who were a very unpopular religious group. In fact, to some people they weren’t a religious group at all. They were looked upon like the Black Panthers or something along those lines, and there was a feeling that if Ali were allowed to escape the draft, it would encourage other young men to join the Muslims. But under our Constitution, every religion has to be recognized, and I always felt it was a case the government would lose in the end. I knew we’d win at trial. At that time, any jury in the United States would have convicted him.”

According to Walker, a rumor was circulating that thirty thousand black Muslims from all over the United States were planning to descend on Houston and stage a mass demonstration outside the courthouse. Racial tensions were already high in the city. At the black Houston university, Texas Southern, eight weeks earlier, a student protest resulted in two buildings being burned to the ground and four students killed. Officials were terrified that the Muslim protest would lead to a race riot. At a pre-trial meeting, U.S. Attorney Mort Susman asked Ali to call the demonstration off.

“He was wonderful about that,” said Walker. “Even with his own problems, he was concerned about someone else getting hurt.”

The outcome of the trial was never in doubt. After a routine presentation of evidence by the government, the defense attempted to prove that the Louisville board that drafted Ali was racially biased because there were no blacks. Ali sat subdued, doodling on a legal pad, as Federal District Court judge Joe Ingraham read his charge to the all-white jury. The only question, said the judge, was whether the defendant knowingly and unlawfully refused to be inducted into military service. The jurors took only twenty-one minutes to find the defendant guilty as charged. On his yellow pad, Ali had drawn a picture of a plane crashing into a mountain.

When the jury returned with its verdict, Ali told the judge, “I’d appreciate it if the court would give me my sentence now instead of waiting and stalling.”

U.S. Attorney Mort Susman, grateful for Ali’s cooperation in calling off the Muslim demonstration, told the Court the government would have no objection if Ali received less than the five-year maximum sentence allowed by law.

“The only record he has is a minor traffic offense,” Susman explained. “He became a Muslim in 1964 after defeating Sonny Liston for the title. This tragedy and the loss of his title can be traced to that.” Susman observed that he had studied the Muslim religion and found it “as much political as it is religious.”

At these words, Ali leaped to his feet and displayed his first emotions since the trial began.

“If I can say so, sir, my religion is not political in any way,” he said.

The judge quickly rebuked him, saying, “YouTl be heard in due order.”

He then imposed the sentence: five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. At this point, Judge Ingraham issued the directive that some believed was worse than the prison sentence. He ordered Ali’s passport confiscated. For the time being, the convicted felon would stay out of prison pending appeal, but the revocation of his passport meant that his boxing career was over. He was already prohibited from fighting in the United States by the actions of state boxing commissions. Now he could not travel to the few countries which still recognized him as world champion.

But if he was worried about what lay ahead, it didn’t show. “I’m giving up my title, my wealth, maybe my future,” he said outside the courtroom. “Many great men have been tested for their religious belief. If I pass this test, I’ll come out stronger than ever.”

The World Boxing Association immediately announced an elimination bout to crown a new champion. Ali reflected the sentiments of many boxing aficionados—even his detractors—when he declared, “Let them have the elimination bouts. Let the man that wins go to the backwoods of Georgia and Alabama or to Sweden or Africa. Let him walk down a back alley at night. Let him stop under a street lamp where some small boys are playing and see what they say. Everybody knows I’m the champion. My ghost will haunt all the arenas. I’ll be there, wearing a sheet and whispering, “Ali-e-e-e! Ali-e-e-e!”