Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (24 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

Those who want to “take” it and hold a series of auction-type bouts not only do me a disservice but actually disgrace themselves. I am certain that the sports fans and fair-minded people throughout America would never accept such a title-holder.

Lieutenant Dunkley looks back on that day and recalls, “As Muhammad Ali walked out of the center, my thoughts were that he had done the wrong thing. I felt that if he would have taken induction they would have put him in Special Services. He probably would have ended up coaching the boxing team or something like that. Or, like Elvis Presley was assigned to a special unit in Germany or something like that. I believe, I’m not positive, but I think Elvis made two movies while he was in the service, and so I think for Ali probably a couple of fights could have been arranged and also he wouldn’t have been stripped of his title as heavyweight champion of the world. So, I felt that he should have taken induction and he should have served his country and that he would have been treated fairly by the U.S. Army, I really do. I think he made a mistake.”

As Ali left the courthouse with his lawyers and stepped into a cab, an elderly white woman approached waving a miniature flag and yelling, “You heading straight for jail! You ain’t no champ no more. You ain’t never gonna be champ no more. You get down on your knees and beg forgiveness from God!” Ali started to answer, but Covington pushed him into the cab. The woman leaned into the window and said, “My son’s in Vietnam, and you no better than he is. He’s there fighting and you here safe. I hope you rot in jail.”

The reverberations of Ali’s decision were swift and decisive. Between the time they left the courthouse and the time they returned to the hotel, less than an hour after his refusal to take the step, the New York State Athletic Commission announced that it had “unanimously decided to suspend Clay’s boxing license indefinitely and to withdraw recognition of him as World Heavyweight champion.”

Columnist Jerry Izenberg recalls the scene. “I didn’t go to Houston to cover the induction, I knew it would be a circus,” he says. “I thought it would be more interesting to station myself at the New York Athletic Commission to see how many seconds it would take them to strip Ali of his title. As it turned out, they did it even faster than I anticipated. It was sickening.”

In fact, the commission had prepared four press releases, anticipating a number of possible scenarios. The one that would have been released had Ali accepted induction praised the boxer for his “patriotism.” The three-member commission had met the previous day and made the decision to strip Ali of his title if he failed to take the step.

Inside the Houston induction center had been two open lines monitoring the events. One led to the Justice Department in Washington, the other to the athletic commission in New York. When Ali emerged from the induction center and announced his decision, the commission wasted little time in issuing the appropriate release.

NYAC chairperson Edwin Dooley, a former Republican congressper-son and college football hero, told reporters, “His refusal to enter the service is regarded by the Commission to be detrimental to the best interests of boxing.”

The World Boxing Association, as well as the Texas and California athletic commissions, immediately followed suit, making it virtually impossible for Ali to fight in the United States. In England, the British board of boxing declared the title vacant. The only dissent from what Ali later called a “legal lynching” was from a number of Muslim countries who continued to recognize Ali as the world champion.

It seemed obvious that Ali would have to stand alone for the time being. But the news of the commission’s decision didn’t seem to faze him. He had other things on his mind as he returned to the hotel. He went up to his room and placed a call to Louisville.

“Mama,” he said into the phone. “I’m all right. I did what I had to do. I sure am looking forward to coming home to eat some of your cooking.”

CHAPTER SEVEN:

Backlash

T

HE PUBLIC AND MEDIA REACTION

had been overwhelmingly hostile after Ali declared he was a Muslim. When he made his first comments about the Vietcong, it had turned vicious. Both responses, however, seemed positively restrained compared to the torrent of abuse unleashed after he refused induction.

The sports editor of his hometown paper, the

Louisville Courier-Journal

—looking forward to the expected jail term—wrote, “Cassius Clay had a responsibility to himself and the boxing game that has given him so much, but Clay is a slick opportunist who clowned his way to the top. Hail to Cassius Clay, the best fighter pound for pound that Leavenworth prison will ever receive.”

Gene Ward warned in the

New York Daily News,

“I do not want my three boys to grow into their teens holding the belief that Cassius Clay is any kind of hero. IT1 do anything to prevent it.”

Milton Gross of the

Post

raged, “Clay seems to have gone past the borders of faith. He has reached the boundaries of fanaticism.”

In an editorial, the

New York Times

indignantly declared, “Citizens cannot pick and choose which wars they wish to fight any more than they can pick and choose which laws they wish to obey.”

The black press, generally supportive of the war, was no more sympathetic; but there, at least, some reporters questioned the government’s motives in drafting Ali. “Clay should serve his time in the Army just like any other young, healthy, all-American boy” wrote James Hicks in Louisville’s black newspaper, the

Defender.

“But what better vehicle to use to put an uppity Negro back in his place than the United States Army.”

In Congress, reaction to Ali’s action was equally fierce. Republican Congressman Robert Michel was incensed that Ali was not thrown in jail immediately after his induction refusal:

It seems totally unfair to me that merely because Clay has made a lot of money, he should be able to stay out of the draft while lawyers prepare a barrage of appeals.

As African-American historian Jeffrey Sammons has observed, “For Ali to score victories in the ring, a circumscribed arena with its own rules, seemed tolerable, but when he took his fight beyond that arena, as his gladiatorial ancestor Spartacus had done, the forces of an ordered white-dominated society responded to the perceived threat.”

But, if scarce, there were a number of liberal writers and intellectuals who supported Ali’s action, particularly in New York, and several of them bonded together to form an ad-hoc committee to push for the boxer’s reinstatement. Among the most prominent members of the committee were Norman Mailer, Pete Hammill, and George Plimpton.

“We all got together and decided to do something because we were outraged by the boxing commission’s action,” recalls Plimpton, at the time a writer for

Sports Illustrated.

“Not because we opposed the Vietnam War—most of us did—but because it was so clearly wrong what they were doing to Ali just because he had the courage to take a stand.”

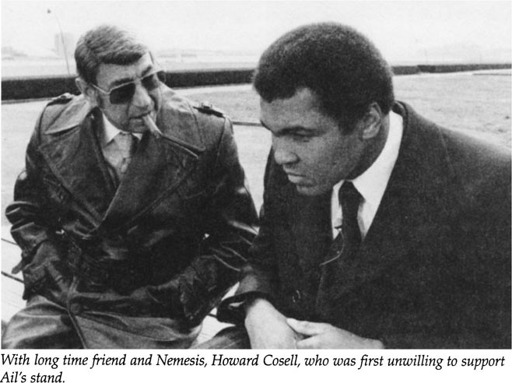

One of the names most conspicuously absent from the committee, however, was ABC boxing commentator Howard Cosell. For almost two years, Cosell had become inextricably linked in the public’s mind with Muhammad Ali. Their association, in fact, came about as a direct result of Ali’s pariah status.

After Ali made his infamous remark about the Vietcong in 1966, the economics of boxing changed dramatically. Before this incident, fight promoters made most of their money selling closed-circuit rights to theaters, where the public would pay to watch the fights. Ali’s anti-war stand, however, prompted veterans groups to threaten theaters with massive boycotts if they dared to show an Ali fight.

In response, ABC television stepped in and signed an exclusive contract to televise Ali’s fights, beginning a new era of televised boxing. Moderating these fights for ABC was a loud-mouthed, nasal-voiced sports radio personality, whose televised exchanges with Ali became the stuff of legend. Each fed off the other’s personality to create a series of classic—and often comical—confrontations. In May 1966, Cosell was in London to cover the Ali fight against Henry Cooper. He started an interview with the champion, announcing to the camera, “I am with Cassius Clay, also known as Muhammad Ali.” His subject turned to him with a glare, saying, “Are you going to do that to me, too?” Cosell responded, “No, I won’t ever do that again as long as I live, I promise. Your name is Muhammad Ali. You’re entitled to that.” From that point, Cosell became known as one of Ali’s most passionate defenders. He later recalled the consequences of this support. “I got thousands of nasty letters and death threats for supporting Ali,” he said, “most of them starting’Cosell, you nigger-loving Jew bastard’!”

Years later, Cosell would express his outrage over the athletic commission’s decision to strip Ali of his title. “It was an outrage,” he told Thomas Hauser shortly before his death, “an absolute disgrace. You know the truth about boxing commissions. They’re nothing but a bunch of politically appointed hacks. Almost without exception, they’re men of such meager talent that the only time you hear anything at all about them is when they’re party to a mismatch that results in a fighter being maimed or killed. And what did they do to Ali! Why? There’d been no grand jury impanelment, no arraignment. Due process of the law hadn’t even begun, yet they took away his livelihood because he failed the test of political and social conformity. Muhammad Ali was stripped of his title and forbidden to fight by all fifty states, and that piece of scum Don King hasn’t been barred by one.”

As Ali’s most high-profile supporter, Cosell seemed a natural member for the committee, and Plimpton was dispatched to enlist his support. But when he got to the TV personality’s ABC office and announced his mission, Cosell quickly cut him off.

“Georgie boy, I’d be shot, sitting right here in this armchair, by some crazed redneck sharpshooter over there in that building,” Plimpton recalls him saying. “If I deigned to say over the airwaves that Muhammad Ali should be completely absolved and allowed to return to the ring, I’d be shot, right through that window.

“My sympathies are obviously with Muhammad. He has no greater friend among the whites, but the time, at this stage in this country’s popular feeling, is not correct for such an act on my part. There is a time and place for everything and this is not it.”

Years later, reviewing Plimpton’s book

Shadowbox,

a

New York Times

reviewer mentioned Plimpton’s assertion that Cosell refused to join the committee.

“I remember Cosell’s wife called me up after the review came out, extremely upset,” Plimpton says. “Cosell himself never said anything about this but his wife got extremely upset and told me Howard had been involved from the very beginning in all this, he’s always been a champion of Muhammad Ali and tried to get me to write a letter of apology, which I did because of my respect for Howard, and to be fair he later came out on Ali’s side. But I remember the incident clearly, Howard would not join us.”

If Plimpton’s recollection doesn’t prove Cosell’s early reluctance to support Ali’s stand against the draft, a column by Jackie Robinson written a month

before

the induction refusal provides good testimony. He refers to an interview with Ali on an episode of ABC’s

Wide World of Sports

in which Cosell seemed to be badgering the boxer about his upcoming induction.

In his syndicated column, Robinson—an Army veteran who supported the Vietnam War and was himself later critical of Ali’s failure to serve—wrote, “I think it is most significant that some of the writers, even the so-called liberals, do not want to grant this young champion his due. One of the sports-writing fraternity whom I have considered a liberal for a long time is Howard Cosell. And Cosell has seemed to be in Clay’s corner for several years. Yet, in a recent television interview with Clay, it struck me that Howard was being quite vicious in the way he tried to sway public opinion to his anti-Clay way of thinking.”

HBO boxing commentator Larry Merchant, who knew Cosell and was an early supporter of Ali, believes the controversial TV personality may have been afraid of jeopardizing his position at ABC. “At the time, Cosell still wasn’t the star he would later become and he may not have been secure enough at ABC in rocking the boat by supporting Ali’s draft stand. It was a very conservative network and they were supporting the war. It was one thing to call him by his Muslim name but this was a much more serious issue,” he explains. “But let’s face it, Howard definitely supported Ali later on, and very publicly. You have to give him credit.”

Cosell seemed to confirm his insecurity in a later interview, although he never acknowledged his early failure to support Ali. “The powers he fought! The forces that lined up against him! Even I wasn’t immune to fear,” he explained. “I supported him, but I often wondered how long ABC would back me. I’d come into the business at a very late age, and could have been snuffed out like that.”

Plimpton and the committee continued their efforts to have Ali reinstated but to no avail. “I was playing in a touch football game at Hickory Hill, Robert Kennedy’s estate,” Plimpton recalls. “And playing with us was Justice Byron White, who was on the Supreme Court. I said, ‘Mr. Justice, isn’t there something very wrong about the Muhammad Ali business, the boxing commission depriving him of his livelihood?’ and he said to me very solemnly that he wasn’t allowed to discuss it because it might come before the Supreme Court.”