Murder and Mayhem (28 page)

Authors: D P Lyle

The victim would develop a severe headache, blurred vision, dizziness, nausea, shortness of breath, confusion and disorientation, perhaps chest pain, perhaps a nosebleed from the high BP, and then collapse and die. These events could occur over several minutes to a few hours, whichever works for you.

As I said, this is a complex topic but an interesting question.

Follow-up Question and Answer

How Does a Physician Distinguish Between a Drug-Induced Fever and One from an Infectious Process?

Q: Could the elevated temperature be misdiagnosed as an infection at first? What would an autopsy pick up in such a situation?

A: Yes, the elevated temperature could lead the M.D. down the wrong road and probably would. An adage in medicine is that "common things occur commonly." A person with very high fever and lethargy or coma or seizures or other neurologic symptoms

would be assumed to have an infection first—particularly an infection of the brain such as meningitis or a brain abscess. Only after these were ruled out would other things be considered. And in the real world a drug interaction with MAOIs in a patient who wasn't taking those medications would not likely even come to mind. Therefore, it would be found only if the M.D. taking care of the victim obtained a drug screen and it appeared there.

The tests to rule out the infections mentioned above could include blood cultures, CT or MRI brain scans, a spinal tap to examine the cerebrospinal fluid for infectious critters and white blood cells, and an EEG (brain wave test), for starters.

In your scenario the victim could collapse or suffer a seizure and be taken to the ER, where her temperature would be found to be 106 and the workup for a brain infection would then ensue. Her blood pressure would likely be very elevated, which can also happen in brain infections if the brain swells and the intracranial pressure (pressure inside the skull) rises. The victim could die in a few hours, which would automatically make it a coroner's case. Anyone who dies within twenty-four hours of hospital admission must at some level be reviewed by the coroner.

The M.D. wouldn't know if the cause of death was indeed an infection or not. The coroner would perform a postmortem exam, find no signs of infection, and would then await the toxicology and other tests before determining the true cause of death. This may take a few days.

Can a Patient Be Killed by the Rapid Injection of Potassium Intravenously?

Q: Does this sound like a credible way for my villain to kill a hospitalized patient? An insulin syringe filled with potassium chloride (40 meq per cc) is injected quickly into an IV line just above the point where the IV's

needle enters the skin. Would there be too much dilution from the IV solution already in the line? If it worked, could this look like a hospital accident if the victim was receiving treatment for dehydration, exposure, and malnourishment? Would he be getting something like potassium chloride to elevate his electrolytes anyway?

A: Absolutely Patients suffering from dehydration and malnutrition often receive IV fluids, which are typically D51/2 normal saline with 40 milliequivalents of KCL per liter. This means a liter (1000 cc) bag of saline which has half the salt (NaCl) of "normal" blood (thus "1/2 Normal Saline") to which 40 meq of potassium chloride (KC1) has been added. It is typically given at 100 to 200 cc per hour, which means the potassium is going at a rate of 4 to 8 meq per hour (40 meq in 1000 cc yields 4 meq per 100 cc).

Giving KC1 faster than 20 meq per hour is dangerous, so the above flow rate is well below that. Pushing 100 meq of KC1 intravenously is obviously way above this, and dilution is nonexistent in "IV push" administration. This dose would stop anyone's heart in seconds.

One caveat: Concentrated KC1 like this burns severely when given, so the patient/victim would react unless he was in a coma or very heavily sedated. Of course he will die quickly, but he would yell out before he fades to black because it burns that severely. Factor this into your plot, and you'll be okay.

Options: The victim could be in a coma or sedated or restrained, and the killer could hold a pillow over his face while giving the KCL. Nurses could be distracted by a Code Blue or an unruly patient at the other end of the hall. The fire alarm could be triggered to create confusion.

If Someone with Tuberculosis Is Smothered, Would There Be Blood on the Pillow?

Q: How would someone look who had been suffocated with a pillow? If the person also had tuberculosis, would the pillow have signs of blood that had been coughed up?

A:

Asphyxia by pillow suffocation leaves less evidence than manual or ligature strangulation because bruises or abrasions on the neck are not present. However, asphyxiations of all types typically result in petechial hemorrhages (also called petechiae) in the conjunctivae of the eyes (the pink mucous membranes that line the eyelids and surround the eyeball). The petechiae are small bright red dots or splotches, usually pinpoint or slightly larger in size. When these are found, some form of asphyxiation is likely, and your M.E. or sleuth would determine this quickly.

In addition, most victims of asphyxia have a deep purple color to their skin, particularly the head, neck, and upper body. Also, if the victim struggles, he may bite his tongue, sometimes severely, or may have the attacker's skin and blood under his fingernails.

As far as TB goes, bleeding would be unlikely but possible. TB is an infection of the lungs caused by

mycobacterium tuberculosis.

This bacterium causes the formation of tubercles (also called granulomas) in the lungs. These are basically small nodules (small round lumps or clumps), microscopic to pinpoint in size, scattered throughout the lungs. They are composed of the bacteria and the various types of white blood cells sent to fight the infection. These tubercles are the body's attempt to wall off or contain the infection.

Occasionally these tubercles will caseate (break down or liquefy), and if so, they may bleed. The patient will then cough up

sputum streaked with blood. We call this hemoptysis. Rarely does the person have severe bleeding.

In your scenario the struggle for air could result in bleeding, but it would likely be streaks of blood, not overt or massive bleeding. The pillow could have streaky bloodstains on it.

THE POLICE AND THE CRIME SCENE

What Does the Wound from a Close-Range Gunshot Look Like?

Q: If a young man is shot at close range in the temple and is found within a two-hour time period, what would the wound look like? Simply a hole? Would it have bruising around it?

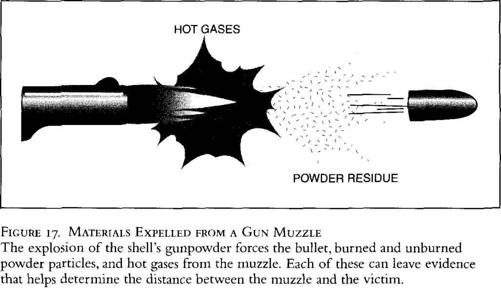

A: When a gun is fired, the muzzle expels more than the bullet. Burned and unburned powder residue and the hot gases produced by the detonated powder are also released (Figure 17). Each of these can alter the resulting wound pattern and may allow the medical examiner to determine the distance between the muzzle and the victim.

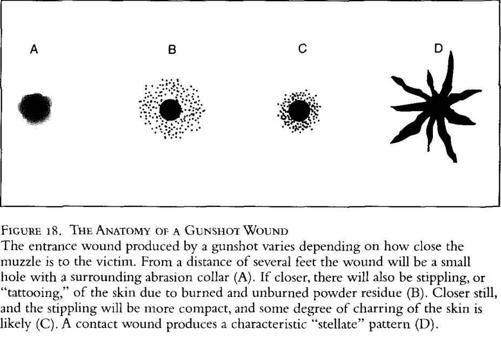

The anatomy of the entrance wound depends on how close the muzzle is to the skin. If it is several feet away, the entrance wound would be a small hole, smaller than the bullet due to the elastic quality of skin (Figure 18a). There would be a blue-black bruising effect in a halo around the entry point (called an "abrasion collar") and some black smudging where the skin literally wipes the bullet clean of the burned powder, grime, and oil residue it picks up during its travel down the barrel. This smudging is often easily wiped away with a wet cloth.

If the muzzle is closer, there may also be "tattooing" or stippling of the skin (Figure 18b). This is due to burned and unburned powder as well as small pieces of the bullet that are discharged from the muzzle. These tiny particles embed in the skin and/or cause tiny hemorrhages (red dots of blood within the skin) in a speckled or splattered pattern around the wound. These cannot be wiped off because the particles are actually embedded (tattooed) into the skin.

If the muzzle is held very close to the skin, the tattooing pattern is more dense and clustered near the wound since there is less distance for the bullet and powder fragments to fan out (Figure 18c). Also, there will be some charring of the skin due to the hot gases of the muzzle blast.

If the muzzle is held against the skin (contact wound), the actual entrance wound may be larger than the bullet, and the charring is likely to be worse. It will also be more ragged and irregular, and often takes on a "stellate" (starlike) pattern (Figure 18d). This is particularly true if the contact wound is over a bone such as the skull in your scenario. This is due to the explosive gases actually tearing the skin around the muzzle as they follow the path of least resistance. The expanding gases cannot expand the gun barrel or the bone, so they escape laterally by tearing through the layers of the skin.

The exit wound would be large and irregular since the bullet would pass through both sides of the skull, and typically each time a bullet strikes bone, it becomes more flattened, misshapen, or mushroomed. This leads to large, irregular exit wounds.

Follow-up Questions and Answers:

Will a Bullet Fired at Close Range Exit the Skull, and If So, Will the M.E. Be Able to Use It for Ballistic Analysis?

Q1: Whether the victim is shot at close range or from several feet away, would the bullet exit the skull?

A1: Your choice. It could or it could not. These things are very unpredictable, and either way is realistic. The physical parameters that determine whether the bullet exits the skull would include the size and weight (caliber) of the bullet, whether the bullet was a hollow point or another type, whether the bullet was jacketed with metal, Teflon, or some other durable coating, the muzzle velocity