Murder and Mayhem (9 page)

Authors: D P Lyle

A: Sorry, but your character is doomed, and his actions would only hasten his demise. Let me explain.

Our skin serves as our radiator. In hot weather the capillaries in the skin dilate, blood flow through the skin increases, and heat is lost to the atmosphere. That is why many people look flushed when they are warm. The evaporation of sweat consumes some of the heat since turning a liquid into a gas (evaporation) requires energy, and it is the body heat that supplies this energy. Thus, heat is lost. People suffering from heat prostration or heatstroke are bathed with water and fanned with a towel or whatever is available.

This promotes evaporation and heat loss from the overheated body of the victim.

Cold is the exact opposite. The body attempts to hold its heat. Blood is diverted away from the skin so that less heat is lost through "the radiator." That is why people look paler when they are cold. When exposed to extremes of cold, the best way to protect yourself from freezing is to cover up, stay out of the wind (moving air absorbs more of the heat), and create warmer ambient air by building an ice cave or burrow of some kind. This traps the body's heat in the "cocoon," and thus less is lost. In water this isn't possible. Similar to a cold wind, the movement of the water or the victim's movements within the water would greatly increase heat loss. During World War II the survival of pilots shot down in the North Atlantic could be measured in minutes.

Now to the brandy issue.

Alcohol dilates the vessels in the skin, which increases blood flow and thus heat loss. Some people become flushed after alcohol consumption. This seems to be especially true with red wine, but it happens with any alcohol. In a cold environment this is the exact opposite of what is desired. The old image of the Saint Bernard with a cask of brandy hanging from his neck is bad medicine. Alcohol hastens heat loss, and thus death from freezing.

Alcohol does not act as antifreeze in the human bloodstream.

In your scenario the man would be up to his neck in frigid water and would likely thrash around in an attempt to stay afloat. The icy water would rapidly dissipate his body heat, and he would become hypothermic (low body temperature) in a matter of ten to twenty minutes, maybe less. If he drank the brandy or was intoxicated before he took the plunge, this time would be shortened considerably. Symptoms of hypothermia include fatigue, weakness, lethargy, and confusion. His strength and coordination would diminish and his survival struggles weaken, and he would drown.

You may remember the dramatic news video of the young woman being rescued from an icy Potomac River. When she was

thrown a line, she was too weak to grip it and sank beneath the water. Fortunately, a heroic man jumped in and saved her. Unless your character had such a hero handy, he would succumb to the cold and drown.

Could your guy survive? Not likely, but there is an old Emergency Department adage that says, "You can't kill a drunk." That is why when you read about a drunk driver hitting a carload of people, it's always the family that dies, never the drunk. Sometimes life doesn't make sense.

Could Someone Survive in a Roadway Tunnel Where a Forest Fire Raged at Both Ends?

Q: This is going to sound like an odd question, but what would happen to a character trapped in a roadway tunnel that cuts through a hillside while a forest fire raged on either end? Would he survive? Would he get burned?

A: Survival would depend on the length and size of the tunnel, whether the fire raged at both ends, whether there was a vent that was away from the fire so that fresh air could be obtained, and other factors. The two dangers would be cooking from the heat and suffocation from the fire consuming the oxygen. If your victim had underlying heart or lung disease, his survival time would be shortened.

The bigger the tunnel, the more air he would have and the farther away from the fire he could stay. If the fire blazed at both ends of the tunnel, it would rapidly consume all the oxygen from the air in the tunnel, and he would suffocate unless a source of fresh air was available—either natural or via some form of breathing apparatus. If it burned only at one end or if a vent was present that was away from the flames, these sources of fresh air would increase his chance of survival. Also, this situation might give him an escape route.

In a short tunnel surrounded by fire, the victim would likely suffocate and cook.

Forest fire fighters carry protective blankets to crawl under and bottled air to breathe just in case the fire overruns them. In most cases this gives them enough protection to survive long enough for the fire to move on. The same could be true for your character. If the tunnel insulated him from the heat and if a source of fresh air was available, he might survive long enough for the fire to move on. Otherwise, he wouldn't.

What Happens When Someone Is Struck by Lightning?

Q: In my story I have a character who is struck by lightning but survives. What kind of injuries might he suffer? What long-term problems would follow?

A: Lightning strikes come in four varieties.

1

. Direct strike:

The lightning hits the victim directly. This is the most serious type and is more likely if the victim is holding a metal object such as a golf club or umbrella.

2.

Flashover.

The lightning travels over the outside of the body. This is more likely if the victim is wearing wet clothing or is covered with sweat.

3.

Side flash:

The current "splashes" from a nearby building, tree, or other person and then spreads to the victim.

4.

Stride potential:

The lightning strikes the ground near the victim, who has one foot closer to the strike than the other. This sets up a potential electrical difference between the legs called a "stride potential." The current enters through one leg, spreads through the body, and exits via the other leg.

When dealing with lightning, which is a direct current, the numbers involved are huge. The voltage varies from 3 million to 200 million volts, and the amperes range from 2,000 to 3,000. Quite a jolt. Fortunately, the current is very brief, averaging from 1 to 100 milliseconds (thousandths of a second).

The injuries that result are primarily due to the massive electrical current and the body's conversion of the electrical energy to heat. The electrical shock can literally stop the heart or cause dangerous and deadly changes in heart rhythm. The heat can burn and char the skin, scorch the clothing, and fuse or melt metal objects in the victim's pockets, buttons on his shirt, belt buckles, and fillings in his teeth.

All the tissues of the body are susceptible to injury. The skin may be charred and even display entry and exit burns. The heart muscle may be damaged and scarred. The liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and muscles may suffer permanent injuries. The brain and spinal cord may be damaged, and residual weakness in an arm or leg is not uncommon. Loss of memory and psychiatric difficulties may follow.

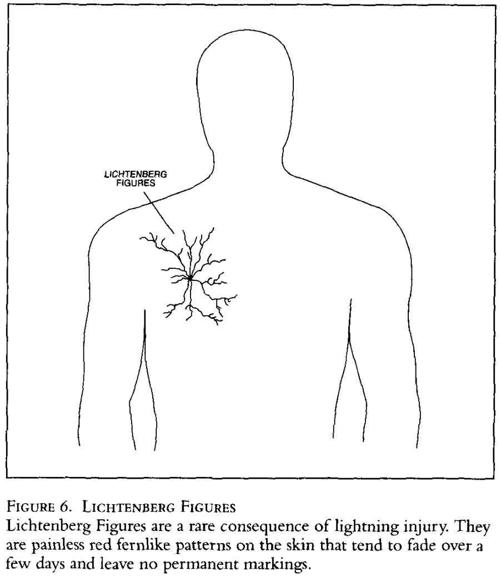

One interesting sign of lightning strikes that rarely occurs are Lichtenberg Figures (Figure 6), which were first described by German physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg in 1777. This is a painless red fernlike or arboresque pattern over the back, shoulders, buttocks, or legs. It tends to fade over a couple of days, leaving behind no scars or discolorations. It is uncommon but fascinating.

Treatment depends on the severity of the injuries. The first order of business is to reestablish breathing and heart rhythm if either or both are absent. Steroids are given to lessen swelling and inflammation in the body's organs. Burns are treated in the usual fashion with cleaning and dressing as indicated. Blood tests would assess the degree of liver, kidney, and muscle damage. When muscles are injured in this fashion, the muscle cells may die or rupture. If so, they release their internal myoglobin and other proteins into the bloodstream. These proteins can severely damage the kidneys because the kidneys attempt to filter them from the blood. Flush-

ing the kidneys with a large amount of IV fluids may prevent kidney failure.

Recovery can be complete, with no residual problems, or the victim may have permanent liver, kidney, cardiac, psychiatric, or neurologic problems. Luck and rapid, effective treatment are important here.

Can a Person Stranded at Sea Survive by Drinking His Own Urine?

Q: If someone was stranded in the desert or on a life raft in the open sea, could he survive by drinking his own urine. Is it dangerous or toxic? Or is it okay?

A: Any port in a storm, so to speak.

Yes, this would help—at first. Urine is simply water with impurities that have been filtered from the blood by the kidneys. In the type of exposure you describe, dehydration is the major problem. Any source of water would be beneficial. However, the concentration of impurities in the urine would increase as dehydration progressed, and very quickly the urine would supply more toxins than water. Drinking it would then be counterproductive.

In reality by the time a person considered drinking his own urine, he would already be severely dehydrated, his urine would be very concentrated, and consuming it would be of little benefit.

DOCTORS, HOSPITALS, AND PARAMEDICAL PERSONNEL

Can X-Ray Films Be Copied?

Q: Can an X ray be photocopied or otherwise duplicated?

A: Yes. X rays are often copied by use of a special copier designed for this purpose. Most hospital radiology departments have such capability, and it takes only a few minutes. Also, nowadays many hospitals acquire and store the images in a digital format. These can be duplicated, printed, altered, e-mailed, and all the other things one can do with digital data.

How Do Doctors Handle Emergencies and Concussions?

Q: In an emergent medical situation, what initial questions might a doctor ask? And if he suspects the person might have sustained a concussion or a more serious head injury, what specific questions might he ask?

A: The initial questions are similar regardless of what the emergent situation is. The key is to get as much information as possible in the shortest time and with the fewest questions. In true emergencies time is often the enemy, and the physician doesn't have the

luxury of taking a long history from the patient. I always taught my students that in such situations you can get most of the information you absolutely need with the following three questions:

1.

What's wrong or what happened?

We call this the "chief complaint." Seventy percent of the time the diagnosis can be narrowed to a very few choices with the answer to this question. A complaint of chest pain leads you in one direction or line of thinking, nausea in another, and headache in yet another.

2. Have you ever been hospitalized or treated for anything in the past, and if so, for what?

We call this the "past medical history." The answer tells the M.D. about the medical problems that the person has experienced in the past and gives him the necessary background to evaluate the current problem. Many of the patient's past illnesses will have an effect on his current illness or injury, and, indeed, many of these past illnesses may still be active medical problems. Heart disease and diabetes would fall into this category since they don't go away but, rather, tend to progress.

3.

Do you take any medications or have any allergies?

This tells the M.D. what the active medical problems are, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, hepatitis, and so forth, and how they are being treated or managed. This information also guides the M.D.'s treatment so he can avoid drug interactions and the use of known allergic drugs.