Murder and Mayhem (7 page)

Authors: D P Lyle

There is one exception, however, that may fit your story needs. The bowel could be bruised and not ruptured or torn, and a hematoma (blood mass or clot) could form in the bowel wall. As the hematoma expanded, it could compromise the blood supply to that section of the bowel. Over a day or two the bowel segment might die. We call this an "ischemic bowel." Ischemia is a term that means interruption of blood flow to an organ. If the bowel segment dies, bleeding would follow. This could allow a three-day delay in the appearance of blood.

In your scenario the injuries would likely be multiple, and so abdominal swelling, the discolorations I described, great pain, fevers, chills, delirium toward the end, and finally bleeding could all occur. This is not a pleasant way to die, but I imagine this happened not infrequently in frontier days.

The victim would be placed in the bed of one of the wa|ons and comforted as much as possible. He might be sponged with water to ease his fevers and offered water or soup, which he would likely vomit; prayers might also be said. He might be given tincture of opium (a liquid). This narcotic would also slow the motility (movement) of the bowel and thus lessen the pain and maybe the bleeding.

Of course, during the time period of your story, your characters wouldn't know any of the internal workings of the injury as I have described. They would only know that he was severely injured and in danger of dying. Some members of the wagon train might have seen similar injuries in the past and would know just how serious the victim's condition was, but they wouldn't understand the physiology behind it. They might even believe that after he survived the first two days he was going to live and then be very shocked when he eventually bled to death. Or they might understand that the bouncing of the wagon over the rough terrain was not only painful but also dangerous for someone in his condition. The train could be halted for the three days he lived, or several wagons could stay behind to tend to him while the rest of the column moved on.

What Was the Technique for Limb Amputation in the Nineteenth Century?

Q: My story takes place in the American frontier in the late 1800s. Near the end of the novel my protagonist must perform an amputation of an arm (a close-range gunshot wound at the elbow, with amputation just above the elbow). Can you tell me the typical procedure followed in an amputation? Blood vessels were badly damaged by the bullet, so I thought the protagonist would first apply a tourniquet. Is that okay? I'm letting the patient have a whiff of ether, so the surgeon may not have to rush through the job.

A: Amputations during the nineteenth century were dangerous and brutal. The ability to repair injured extremities and to control infections in gangrenous limbs did not exist at that time, and amputation was viewed as the only hope to save the victim. However, blood loss followed by shock and death or infection of the

remaining stump dogged the surgeon's every effort. There was no blood to replace losses and treat shock, and antibiotics did not exist. Even with a successful procedure, the victim could die, and often did, from continued bleeding or infection.

The surgeon attempted to perform the procedure as rapidly as possible since it was very painful, and in frontier areas or during times of war anesthetic agents weren't readily available. A typical anesthetic was alcohol and sometimes tincture of opium or ether. Dr. Crawford Long first employed ether in surgery in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1842. The first public demonstration of its use took place in Boston in 1846, so it would be realistic for your protagonist to have access to it.

Even with a whiff of ether, the patient would likely have to be restrained by some of the stronger members of the community. A strip of leather or a piece of wood to bite down on might be employed.

As a medical student I scrubbed in on a couple of amputations. I came away with the impression that it remains a fairly brutal procedure with knives and saws and chisels and hammers. Yet even after those experiences, the most vivid image I have of this procedure is still the dramatic scene in

Gone with the Wind.

Yes, a tourniquet would be tied very tightly around the extremity to prevent bleeding from the arteries that the surgeon would have to cut through. In your situation this would be done at the mid-humeral (upper arm) area. A large knife would be used to cut the tissues circumferentially (all the way around) down to the bone, and then a handsaw would complete the process. The stump would then be cauterized with a hot blade or other piece of metal heated over a fire and dressed with the cleanest pieces of cloth available.

The mortality rate for these procedures in the late 1800s was 50 percent or more. Most deaths occurred fairly quickly due to bleeding and shock; other victims lingered for days or weeks before succumbing to infection.

What Are the Physical Limitations of Someone with a Shoulder Dislocation?

Q: A character in a story I'm writing needs to be stuck in a remote hunting camp for two or three days with a dislocated shoulder. These are my questions:

1. If he doesn't get immediate treatment, will the damage continue to increase, or does the condition stay about the same?

2. What symptoms would he have? Will the immediate pain of the dislocation subside or get worse over the two to three days it goes untreated?

3. What kind of dysfunction will he have? Will he be able to use the arm at all? If he can't use or move the shoulder, will he still be able to grip things with the hand or lift very light objects?

4. When he does finally get treatment, exactly what is done for such an injury? How long will he be out of commission? If he was really tough, could he get back into action within a day or two?

A: The shoulder is one of the most—if not the most—complex joints in the body. Its range of motion is wide. It can hinge like the knee, rotate like the hip, and even whirl around in a circle like a windmill. It is basically a ball-and-socket joint, with the ball being the head of the humerus (upper arm bone) and the socket being formed by the glenoid cavity and the acromion of the scapula (shoulder blade). The above-mentioned portions of the scapula, the several ligaments that hold the humerus and the scapula together, and an inner lining of cartilage, which provides a smooth friction-

free cuplike enclosure for the "ball" of the humerus to move within, form the joint capsule.

A dislocation occurs when the ball is forced out of the socket. Direct trauma to the shoulder or a severe torquing of the arm are the usual causes. Football players, gymnasts, and children yanked up by their arms are common victims of this type of shoulder injury.

The pain is immediate and severe, but once the dislocation has been "reduced" (the ball returned to the socket), the pain is minimal at that time. However, over the next several hours bleeding into the joint occurs, the muscles around the joint spasm (contract) in an attempt to stabilize the joint, and the pain returns. Any movement in any direction results in a knifelike stabbing pain in the shoulder. The first three or four days are the worst, but pain and limited motion may last for weeks or months. I have personal knowledge here—nine times. Football is a great sport.

Reducing the dislocation (manipulating or popping it back into place) can be accomplished in several ways. Sometimes merely raising the arm outward will pop it back into place. If another person is present, that person can drape the injured arm over his own shoulder (with the victim standing behind him) and lift the victim up on his back by bending forward. This pulls the humerus forward and outward, and often it will slip back into the socket. This can also be accomplished by laying the victim on his back, grasping his wrist, placing a foot against his chest near his axilla (armpit), and pulling his arm out to the side. This will pull the humeral head outward, and it often reseats itself in the socket. (Don't try any of these unless you know what you're doing because if it is done improperly, further injury may occur.) In your situation the victim could tie a rope around his wrist, attach the other end to a tree or rock, and pull the arm out to reduce the dislocation.

The sooner the shoulder dislocation is reduced, the better. Once the muscles spasm, reduction may be very difficult. Also, the nerves and blood vessels that go out to the arm pass beneath the shoulder, through the axilla. The pulse of the subclavian artery can be felt in

the armpit. The dislocation can damage these vital conduits, and short- and long-term problems can result. Vascular damage can lead to ischemia (poor blood supply) of the arm, hematoma (a large collection of blood) formation, and possibly the development of an aneurysm (swelling of the artery). Nerve damage can cause loss of motor function (paralysis or weakness) and abnormal sensory function (numbness, tingling, loss of coordination, or diminished sense of touch and feel).

If the shoulder cannot be reduced, the injured person's limitations would be severe. He could not move the shoulder, and if the nerves were damaged or stretched, he might not be able to use his hand. If the dislocation was reduced, he would be able to function well for a few hours until the spasm sets in. After that the shoulder would be "frozen" and very painful with even the slightest movement. He should be able to bend his elbow and use his hands without a problem.

The typical treatment of a simple dislocation is to reduce it, place the arm in a sling, which is strapped to the chest to prevent shoulder movement, administer pain medications, and give it time to heal. If the injury is more complex, with severe damage to the joint capsule or with vascular or nerve injury, surgery may be required.

It would take several months for the shoulder to heal completely, but with a simple dislocation he should be able to move the shoulder carefully and do most things after a couple of weeks.

What Are the Symptoms and Treatment of a "Sucking Chest Wound"?

Q: I have a question about sucking chest wounds. I've written a scene in which a Vietnam War veteran applies a modified field dressing to his buddy's chest wound roughly ten minutes after the injury is sustained, but I

wonder if I'm stretching credibility by having my victim able to conduct a conversation with my hero. What do you think? Is the injured man likely to survive?

A: First, let's look at "sucking chest wounds." I know, I know, having any wound to the chest sucks, but there is a real medical entity that goes by this moniker. Any object that penetrates the chest wall and leaves behind an open wound would result in a sucking chest wound. In a gunshot wound (GSW) to the chest, the bullet typically makes a small hole as it travels through the tissues of the chest wall. These tissues are elastic and tend to recoil and collapse around the path of the bullet, closing it off and obliterating any opening to the outside. This may penetrate and collapse the lung, and it may be fatal, but it isn't likely to produce a sucking chest wound. The exit wound, however, may be large enough.

A larger wound, such as from explosive shrapnel or a spear or a highway guardrail in an automobile accident or the above-mentioned GSW exit wound, will not close in this fashion simply due to the larger diameter of the wound. This leaves an opening to the outside.

Breathing, drawing air into the lungs, depends on the production of a negative pressure within the chest as the diaphragm lowers and the chest expands. This pulls air into the lungs. During exhalation this process is reversed, and air is forced back out of the lungs. Close your mouth, pinch your nose, and try to breathe in and out. Negative pressure during attempted inhalation and positive pressure during attempted exhalation are produced, but no air moves because you have created a closed system and there is no opening to the outside through which air can enter and exit.

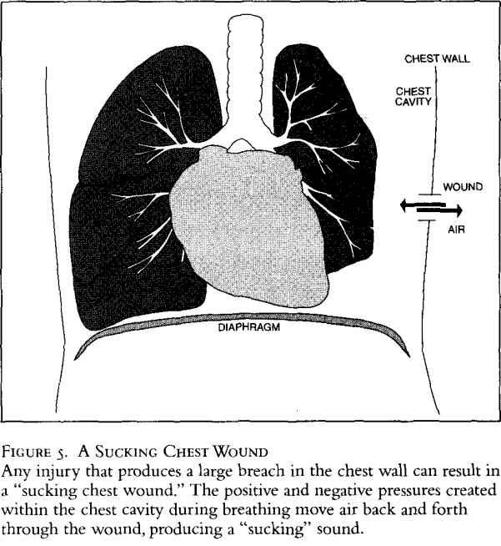

With a wound that produces a large enough opening in the chest wall, the normal expansion of the chest during inhalation sucks air from the outside, through the wound, and into the chest cavity, in the space between the lung and the chest wall. With exhalation air is forced back through the opening and out of the

chest cavity (Figure 5). The lung on the injured side will collapse, and a sucking sound is made with each inhalation and exhalation as air moves back and forth through the wound—thus the name "sucking chest wound." Fortunately, each lung is self-contained on its side of the chest, so that the lung on the uninjured side will remain inflated and function normally.

No, waiting ten minutes for help isn't a problem. Even an hour is okay if the person is otherwise healthy. The victim would survive and be able to speak with only one lung for quite some time. He would be short of breath, cough a lot, and be in pain, and fear would be a big factor, but he would live.