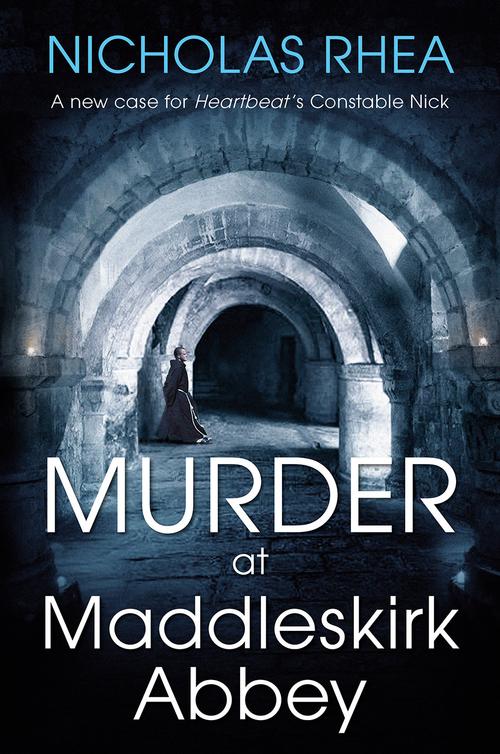

Murder at Maddleskirk Abbey

Read Murder at Maddleskirk Abbey Online

Authors: Nicholas Rhea

at

Maddleskirk

Abbey

Nicholas Rhea

W

HEN

I

ANSWERED

the phone during breakfast on Monday morning, a rather breathless voice gasped, ‘Nick, can you come quickly? To meet me at the crypt?’

‘It’s the prior, isn’t it?’ Despite the anxiety in his voice, I recognized his distinctive accent. It was a delightful

combination

of his native Irish and the lilt of Northumberland.

‘Yes it is. Can you come straight away?’

‘Is there a problem?’ I’m always cautious about reacting to events rather too swiftly, as I like to know what I’m letting myself in for.

‘We’ve found a body. We don’t know who it is. It’s all very peculiar. I’d appreciate your advice.’

‘A body? Peculiar, you say?’

‘A man, he’s dead. Lying in a coffin in the crypt. A huge stone coffin. We’re not sure what to do next.’

‘It’s not an ancient burial, is it? You’ve not discovered a medieval grave with its occupant?’

‘No. The coffin might be from a bygone age, but the body’s not. He’s as modern as we are.’

‘Have you told the county police? Or a doctor?’

‘A doctor, yes. Then I thought I’d contact you, you’ll know what to do.’

‘Don’t touch or move anything I’ll be there in a couple of minutes.’

It was a few minutes past eight on a bright sunny morning in early summer, a complete contrast to the previous night’s

damaging gales and torrential downpours. Things were calm now but the radio had said there were reports of damage throughout the region with some roads blocked and buildings damaged by falling trees. There were also reports of floods, along with damage and the ruination of crops. Although we had experienced the storm in and around Maddleskirk, the village and its environs, including the abbey, seemed to have escaped lightly despite being surrounded by deciduous woods. But storm or no storm, life, death and work had to continue.

It was Monday and a new working week was underway for the staff and monks of Maddleskirk Abbey. Gulping down the last of my coffee, I told Mary I had to rush off because a body had been found at the abbey. She groaned, and muttered

something

about me no longer being a police officer, adding her strong opinion that the discovery had absolutely nothing to do with me. She remarked that such things were the responsibility of the local police and not of a retired inspector.

I reminded her that having helped very recently to create the abbey’s brand new private police force I held one of their warrant cards and had been sworn in by a magistrate so I was officially a police officer and furthermore I was paid a useful retainer for my services. It meant I had some responsibility for actions by its members, all of whom were very inexperienced in police work when it came to serious crime. Dealing with a dead body was not part of their daily monastic routine either, but the prior’s call hinted at something mysterious – peculiar, as he had said. The overall role of the monk-constables was keeping the peace and supervising the security of the vast abbey campus.

Putting my empty mug on the draining board, I told Mary that both she and I had additional new responsibilities with my unexpected inheritance of several acres of woodland adjoining the southern boundary of Maddleskirk Abbey estate. It included an old building known as Ashwell Barns and even a holy well, both part of the ancient but ruined Ashwell Priory. I had heard about my good fortune less than a week before and

had not told anyone except Mary, nor had I signed any papers, so neither the Abbey Trustees nor the abbot knew of my

inheritance

. That alone gave me an added interest in anything connected with Maddleskirk Abbey – now we were close neighbours. But that was a secret I did not want revealed.

There had been no suggestion the body might be lying on my land, but that was not impossible – the old priory had been buried for centuries. Not surprisingly I was keen to learn more about my inheritance but not just yet. I explained to Mary that I had no idea how long I would be away; it might be just a few minutes – if the fellow had suffered a heart attack or something similar, it would not be a matter for the police and I could advise them accordingly, then come home. Maddleskirk Abbey was only a couple of minutes away by car and there was ample parking with a space directly outside the crypt entrance.

During the short drive, I acknowledged there were bound to be instances when the brand new monk-constables sought advice. The monkstables – as everyone was already calling them – were private police officers whose duty was to

supervise

and deal with all aspects of security in and around the Abbey complex. That included Maddleskirk College, a private school that currently accepted boys only, though the admission of girls was likely within a year or so. The abbey estate had its own working farm along with a host of other facilities, indoors and out, all adding up to an establishment as busy and

populous

as a large village or small market town. It had its own theatre, cinema, sports centre, swimming pool, two infirmaries (one for monks and the other for students), two libraries (one in the monastery and the other in the College), a visitor centre, an ambulance, a fire brigade, post office and shop. There were also accommodation blocks for the pupils and domestic staff, and rows of houses for the teachers and other workers.

When on police duty, the monkstables wore black police uniforms, white helmets and clerical collars, reverting to their black habits during normal priestly activities. They were

sometimes

called Black Friars or Black Monks and formed the first

private police force in Britain to consist entirely of monks, and the abbey’s own fire brigade comprised monks trained by the county fire service. The monkstables were recruited from Maddleskirk Abbey’s resident Benedictine community. York Minster, Salisbury Cathedral and Cambridge University all made use of private, non-clerical police officers for their internal security.

In the case of Maddleskirk, I had been fortunate to have the help of retired Sergeant Blaketon and ex-PC Ventress from Ashfordly Police. Together we had trained the force of nine recruits in police law and procedure to a standard that would enable them to deal with fairly routine duties in and around the abbey and college. Further afield, their responsibilities included churches, chapels, parishes and other properties owned by Maddleskirk Abbey. From time to time, one or two monkstables would patrol them and deal with minor security matters.

Prior Gabriel Tuck, head of the eight-strong police unit, was also deputy to the abbot and he was clearly worried about the discovery of a man’s body. The fact he had called me suggested this was not a normal death – on occasions, visitors had collapsed and died within the complex and, in most cases, the deaths had been dealt with by the abbey’s own infirmary and medical staff. At least two of the monks were qualified doctors, one also being a surgeon. However, Prior Tuck had come from a different background: he was a former police officer.

The prior was a jolly, rounded individual with a

mischievous

sense of humour and a yearning to organize a slap-up feast to celebrate almost anything that deserved praise. He was also very partial to Mars Bars and carried a supply in a pocket hidden somewhere within his habit. His few years of police service had been in Northumbria, so it was not surprising he had been invited by the abbot to lead the tiny in-house police force. Among the Maddleskirk community several monks had names that reminded the prior of Robin Hood and his Merry Men. Indeed, the abbot was called Merryman and many of the

students referred to the prior as Friar Tuck. He and his monkstables lived up to Robin Hood’s reputation by suggesting to offenders they might care to donate something to charity as penance for a minor transgression. These were likely to be litter-droppers, noisy youngsters, careless car-parkers or inquisitive women wandering “accidentally” into the monastic corridors. Most offenders responded to an invitation to donate funds to charity. Major crime was rarely within the scope of the monkstables and if something serious happened, the county constabulary would be called in.

That was why Prior Tuck had rung me. As I drove the short distance, I recalled that Abbot Merryman was the equivalent of a managing director or chairman of a multi-million pound corporation, but in his case much of that work was conducted in addition to his demanding monastic duties. The sheer scale and complexity of the abbey’s numerous functions never failed to impress me. In addition to its college campus, it was surrounded by constant activity, much of it involving hundreds of building workers engaged on a massive expansion programme that included new buildings and the upgrading of older ones. The abbey was being bullied into acknowledging the twenty-first century.

As if that wasn’t enough, a small archaeological excavation was underway under a marquee in a corner of one of the cricket fields. It lay beside the internal road I was now using. Known as George’s Field, it had been created from a patch of rough ground to become a splendid cricket pitch that was maintained in prime condition. This year it was ‘resting’ to allow its several worn pitches and outfield to recover from constant use. As I drove past slowly, I saw the sides of the marquee had been raised to allow in light and fresh air, and I could see six or seven people at work. Parked nearby on the field were a white camper-van and a six-seater people carrier. I had been told that this excavation resulted from an aerial photograph that had indicated the outlines of what might be medieval or even Roman buildings underground.

Certainly there had been a Roman settlement in the dale and to the trained eye, the routes of some Roman roads were still visible on the surrounding hills. The presence of the

archaeologists

had sparked off a good deal of speculation both in the village and the abbey campus and we had been told they were expecting to confirm either a Roman settlement or a medieval structure. I drove past without stopping and followed several builders’ vehicles and private cars which were also making their way into the grounds. It was a form of rural rush hour in this normally peaceful setting. In addition to those going to work, I encountered several who were leaving the abbey and college and travelling home in the opposite direction. A cyclist with his helmeted head down was pedalling against the flow of traffic and dodging fallen branches and twigs. There was a hiker who had perhaps spent the night in guest

accommodation

, and several young women who worked short early shifts, perhaps cleaners, kitchen workers or waitresses. Pupils and monks had early breakfasts in separate dining areas, whilst guests on retreats were fed in the Retreat Centre. Occasionally after breakfast, guests walked against the flow of traffic into Maddleskirk village to buy a newspaper or obtain something else from the shop which opened at seven. So, the hours between seven and nine in the morning were very busy for the abbey and college whilst within it all the community of monks would be quietly undertaking their own specialist work with prayers. In the abbey church, matins would be over with lauds just finishing. Clearly the prior had been summoned from lauds to deal with the body.

Hoping to find a parking place I wondered if last night’s storms had damaged any of the buildings currently under construction, or indeed the woodland and buildings on the patch of land I had inherited. I would check before I went home.

As I drove towards the abbey church I wondered where exactly to find the coffin. The crypt, sometimes known as the undercroft, was a massive underground area containing the

meagre remains of yet another medieval abbey. It had once been known as Ashlea Abbey. I wondered if this former abbey had been associated with the old Ashwell Priory that I had inherited. A priory was a monastic establishment that was governed by its parent abbey, although some priories were known as cells.

The modern abbey church of Maddleskirk had been constructed around 1950, directly above the Ashlea ruins as a result of which the ancient stones and pillars had become the modern crypt. Due to a lack of windows, poor lighting and the ever-present uncertainty about safety of its old stonework, which did not bear the weight of the new church above, access to crypt was not actively encouraged but neither was it forbidden. Mass was celebrated daily in one or other of its thirty-six chapels. Guided tours were possible with a monk to oversee the conduct and safety of the visitors, particularly the infirm or schoolchildren.

There were three entrances, one of which was to the south; that door was close to the long flight of steps that led into the modern church via its own door which was the one I would now use. I parked and locked the car but there was no sign of Prior Tuck. I guessed he would be inside. I opened the heavy wooden door and could see the eerie crypt illuminated by dim lights so I left the door open to benefit from daylight. I was familiar with the place having often attended mass or other functions in the chapels, and knew about the legend of vast treasure supposedly hidden in an underground tunnel guarded by a giant raven. The modern church had been built into the heavily wooded hillside to make its crypt like a gigantic dark cellar smelling of age and dampness.

Architects had claimed the crypt was quite safe because it bore none of the enormous weight and strains from above; in effect, the church straddled the old and protected it like a mother hen caring for her chick. As I entered the vast dark

interior

, the clock was striking quarter past eight and I saw a large man in black clothes to my right, a few yards away but close to

the Lady Chapel. I thought it was a monk in his habit, but, as I walked past, I saw he was working at a bench with the aid of strong lights. He was noisily sorting through a mass of tools spread about his bench and was quite unaware of me. I realized it was a sculptor. Some weeks ago I’d been told he was working on a triptych featuring three scenes from the Crucifixion. The commission was a gift from a benefactor and when finished, it would be inset within a wall of the Lady Chapel. I shouted ‘Good morning’ but received no reply. The noise of his activity drowned my voice and such was his concentration that he seemed unaware of what was happening around him.