My Father's Fortune (24 page)

Read My Father's Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Frayn

Year after year he gets the language sixth through their A-levels. He propels them into Oxford and Cambridge. He does more â he persuades us to be interested in Racine, even if not quite in Corneille. He has us performing Schiller and reading Thomas Mann. Nor does he stop at the official syllabus. Every winter he organises an entertainment for the French Circle and another for the German Circle. In fact the Doctor and his entertainments

are

the French and German Circles, and they have the reassuring familiarity of Christmas. A boy called Loveday plays a violin solo by a French or German composer. Someone recites

Le Corbeau et le

renard

or sings

Die Lorelei

. William Tell shoots Gessler. There's even an audience; the Doctor has gone round the school collecting one, largely by the lobes of their ears, or possibly, in the case of the younger boys, simply by terrifying them into acquiescence by the weirdness of his appearance. None of the audience understands a word of the performance in either language, but everyone claps and cheers, and only in part ironically.

In any case the evening always ends with a straightforward sing-song â a scene set in a French café or a German beer garden, with the whole cast in Lederhosen or berets and striped vests, raising glasses of cherryade or ginger beer and singing

Santa Lucia

(Italian, it's true, which none of us is doing, but the Doctor has wide European horizons), accompanied by Loveday on the violin, Pratt on the piano-accordion â and the Doctor himself, lurking hugely at the back like an unsteady Eiffel Tower and playing the double bass, on which I suppose the fingering's sufficiently widely spaced for him to hit something approximating to quite a lot of the notes.

In the middle of one of these finales there's a crash like a house falling down, as the Doctor and his double bass suddenly disappear from view. They've wobbled off the back of the stage together, and fallen horizontally on to the floor three feet below.

Santa Lucia

wavers, and then continues. The Doctor and bass reappear on

stage in time for the last chorus, the Doctor's wrinkled walnut face split by the lopsided grin with which he usually (not always) manages to greet disasters of this sort. One day in class his sudden compulsive twitches are too much for the chair he's sitting on, and with a crunch of breaking timber he vanishes behind the desk as abruptly as from the stage. Mocking cheers from the class. When his head slowly rises above the horizon, like some strange moon, he's clearly in both pain and shock. âRemember your religion, sir!' calls Grandjean. The moon cracks into its heroic grin.

He often finds time in class for jokes. They're usually the same two, so we get to understand them quite well. The first is very short, about the Frenchman whose new trousers are

Toulouse et

Toulon

. The second one's more extended. It concerns a resting actor who's hired to play the part of a major-domo at some grand occasion. All he has to do is to dress up in eighteenth-century costume, walk slowly and solemnly on to the stage, turn to face the audience, thump on the floor three times with a silver-topped staff and cry in a resoundingly authoritative voice: âSilence!' The actor rehearses the performance many times until it's perfect. The great occasion arrives. On to the stage he slowly and solemnly marches. Turns to face the audience. Thumps three times with his silver-topped staff. Then suddenly loses his nerve. â'Ush!' he squeaks. This second joke has a serious educational message about how easy it is for even the best prepared candidate to panic in an exam. The first, I think, has no particular pedagogic function. Both give the Doctor great delight, however often he tells them.

As well as favourite jokes he has favourite pupils, and usually about the same number of them. For a time I'm one. âHis receptivity makes it a real pleasure to teach him,' he writes in his first report on me. (Entirely legibly, I see, now that I've found it in an ancient file, so I suppose he must have got someone to write it for him.) My star begins to fade, though, as time goes on, and then sets as abruptly as the Doctor himself on the breaking chair when I try to liven up the unwelcome prospect of writing yet another literary essay, and on a subject I find particulary dreary â

âclle & t dePictm o ancient rum' (âCorneille and the depiction of ancient Rome'), by doing it not in English prose but in French verse. In alexandrines, to be precise, the way Corneille himself depicted ancient Rome, which are not an easy form, though I don't suppose they're very good alexandrines. Most schoolteachers, in my experience, can switch with disconcerting suddenness from sunshine to thunder, and the Doctor does so now. He sends me, alexandrines in hand, to the headmaster, who finds it difficult to keep a straight face, even before he reads the verses, and mildly recommends me to stick in future to English prose. Lucky for me, perhaps, that I'm not up before the Reverend J. B. Lawton. Uncalled-for alexandrines would probably have merited the cat-o'-nine-tails.

Lane and I are both back before the headmaster for cutting French to watch the Labour Party losing the 1951 election, and my diary later records âa series of rows with the Doctor', but in between whiles we must have made our peace. There are only four of us doing German, and it's going to be difficult to produce

Wil

helm Tell

, which has a cast of fifty, if even one of us is alienated. He invites me with the rest of the language sixth for his annual treat, chocolate éclairs in the Oak Lounge at Bentalls, then accords me an even greater favour â tea at his home, the gloomy Victorian house in Surbiton where he's looked after by his two adoring sisters, and where he takes me on a guided tour of the collection he has assembled over the years: irregular lumps of stone, indistinguishable one from another without his expert commentary, that he has broken off the leading cathedrals of Europe.

*

We're coming to the end of this chapter of the story. Of school, of our great friendship. Of living with parents and step-parents, of agonising over girls under the suburban sodium lights. Just our last exams to sit, and then we shall be going our separate ways. Me into the army, Lane into the RAF, to do our National Service. Then for me, if I get in, university. Life.

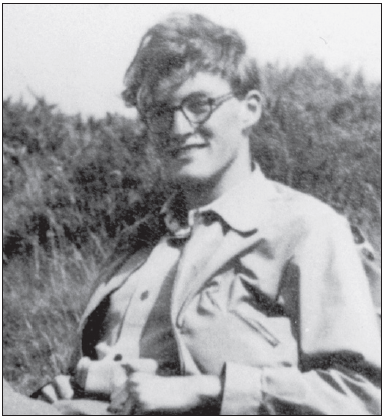

We make one last trip together. We hitch-hike down to South Wales and walk over the Brecon Beacons and the Black Mountains, talking, of course, singing, drinking beer in pubs and smoking â I seem to recall a pipe by this time. I have a picture that Lane took of me on our last day. I'm in my walking boots, sitting on the upland grass and reclining against my rucksack, the wind in my hair. I look relaxed and happy. There's not the trace of a sneer on my face.

My father winked and clicked his tongue respectfully about Cambridge as we walked round it five or six years earlier. Now the prospect begins to take shape of my actually stepping through one of those college gateways myself into the sunlit world beyond â and he baulks.

How has the idea come up at all? I think because the school simply assumes that if you have a chance of Oxford or Cambridge you take it. This is what good grammar schools do at the time. You stay in the sixth form for a third year and prepare for college entrance; you try for a scholarship or an exhibition. So this is the timetable my father sees: a third year wasted in the sixth form, another two doing National Service, then three more frittered away at Cambridge. By the time I emerge to face what's now called the real world I shall be twenty-five â eleven years older than he was when he first got a job and started earning his living.

I share the assumptions of the school â but I also share my father's doubts and impatience. In a spirit of compromise, I suppose, if only with myself, I decide to miss out the third year in the sixth form and take Cambridge entrance in the second year, which means that I shall have to be interviewed in my first. Before my initial shine is tarnished by the alexandrines, therefore, while I'm still a pleasure to teach, the Doctor arranges for me to go up to Cambridge and be seen by someone he knows personally.

I don't think I'm fully aware at this point that Cambridge is made up of separate colleges, and that behind each of those dark gateways lies a largely autonomous institution with its own character and peculiarities. The name that the Doctor has written down for me, Emmanuel, or more probably Emmql, has no significance

for me except as the address where I'm to meet Dr weLbn, aka Welbourne. I certainly have no idea that Emmanuel at this time is a sporting college which particularly specialises in boxing, where existential anguish is unknown, or that Welbourne is a much-loved local character who's celebrated for his amusing anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism. All I know is that at an interview of this sort you must be carrying the

Manchester Guardian

under your arm. I've never seen the paper before, but I buy a copy at Liverpool Street, and discover under the heading âUniversity News', as I read it on the train, that Dr Welbourne, Senior Tutor of Emmanuel, has just been elected Master, so with improbable urbanity I begin the interview by congratulating him. The only other thing I can remember about the occasion is one of his questions (though not my answer): âSupposing in years to come you are married and have children. Your children go on a school exchange to France. When they come back you discover that they have been converted to Roman Catholicism. What would your attitude be?'

Impressed either by my knowledge of college politics or my readiness to subject my hypothetical children to rack and thumbscrew until they recant their hypothetical apostasy, he invites me to take the college entrance exam that Christmas, and I manage (just) to scrape a place. My father remains implacable. He declines to find the maintenance allowance I should need of some

£

300 a year. I suppose he sees a university as simply a way of getting into a job, and as dispensable as a ladder is for getting into a loft. I can't really blame him â not, at any rate, with the benevolence of hindsight. I've already had four years more education than he had himself, and the benefits both to my employability and to my general character are far from obvious. Any further doses of education are likely to make both even worse.

My winning (just) a State Scholarship on the results of my A-levels that summer softens him briefly â until the Ministry of Education discovers how well-off my parents are between them. My grant will be only the nominal minimum of

£

30; my father will have to find the balance himself. Again he refuses. Once I've

finished my National Service, when I shall already be twenty-one, I shall have to look for a job. What as? I suppose I might have some faint hope of becoming a reporter on the

Epsom and Ewell

Gazette

. Or perhaps my father still nurses some even fainter hope of my becoming an asbestos rep. One way or another, though, I'm going to have to start earning my living.

I see, now I think about it, that his expectations of my future are shadowed by his experiences of the past. He looks at me and sees his father and his wife's father, neither of them â even without the debilitating effects of higher education â able to keep a job, neither of them able to support himself or his family. He has spent the first thirty-odd years of his working life maintaining them and their dependants. He can see himself spending the rest of it doing the same for me.

So what happens next is mystifying. He challenges the Ministry's decision. Is this at my urging, or the school's, or has he had second thoughts himself? Still stranger are the grounds for his challenge. He informs the Ministry that my stepmother's resources are not available for my education. This is an entirely specious argument. Whether or not Elsie is prepared to open her handbag and dole out the money to me direct, she's paying most of my father's other expenses in life. I suppose he still has to find my sister's school fees, and the cost of his new suits, and the entrance fees for the paddock at Goodwood and Ascot, but I'm obviously an indirect beneficiary of Elsie's wealth.

All this is curious enough; even less comprehensible is the Ministry's response. They accept my father's argument, though even on the basis of his income alone they will not pay me more than

£

168 a year. At this point he graciously concedes and agrees to give me the other

£

115. So in a way he has got me into Cambridge, just as six years earlier he got me into the grammar school. I'm saved from the real world for another three years. Or the real world is saved from me, as my father probably sees it.

First, though, my National Service â and this, as it turns out, is not the waste of time that I've been expecting just as much as he

has. My rising tide of good fortune continues. I don't spend the next two years peeling potatoes or whitewashing coal. Nor am I sent, like so many other national servicemen at the time, to risk being killed in Korea, Malaya or Kenya. Within a few weeks of being marched with my apprehensive fellow conscripts into the grim khaki universe of the Royal Artillery's huge basic training camp at Oswestry I'm out of it again, and have been sent off to learn Russian. Another couple of months and I'm being trained as an interpreter â at Cambridge, in fact, two years before I'm due to arrive as an undergraduate.

No literary essays, much translation. Away from home, with money in my pocket and congenial comrades. In my diary for the next few months there's no trace of existential anguish. âLife has never been so enjoyable ⦠A calm river of contentment which flows on and on â¦'

That calm river doesn't flow on for ever, of course. A few months later I'm managing to be disgusted at myself for enjoying everything so much. The rest of my life, though, at Cambridge and beyond, now that my father has helped launch me upon it, is another story, and not one that I'm going to tell here.

*

My relations with my father, now I have a little more distance from him, get paradoxically closer. My journal has shrunk from substantial essays in a substantial ledger to brief paragraphs in a pocket engagement diary, but I still find space to record a number of joint expeditions. We go for walks together (one of them over the Seven Sisters, perhaps as an allusion to the road around which so much of our family's life has centred: âa delightful day'.) A concert at the Festival Hall (âI enjoyed it very much, but Pa heard almost nothing'). The races, where I try to enter into the spirit of things by putting the occasional five bob on a horse being led round the paddock by a pretty stable girl. Billiards in a hall in Epsom where no daylight has been admitted since the blackout â nor air, by the smell of it â and where we're probably the only customers without criminal records. On Coronation Day, when Elsie has invited all the neighbours in to watch proceedings on the television in the living room, my father and I, having no interest in the Queen or her crown, spend a very congenial day in the breakfast room, cutting sandwiches for Elsie's guests and drinking beer together. On Midsummer's Day 1953, when I'm home on leave again, âPa and I talked about the stupidity of the army, the brutality of the Russians etc until half-past twelve.'

There are also some of the same old squalls. My diary records a row with him about âintellectual snobbery' (mine, I imagine, not his), and another about âState of my Room'. (âWhat right has he got? Oh blast, fed up. Went and climbed trees â¦') When I'm commissioned, though, and have to open a bank account to get my pay as an officer, he takes me down to Barclay's Bank in Ewell Village and introduces me to the manager, then shows me how to

keep a monthly tally of incomings and outgoings. It's not quite double entry, but it's good enough to save me from having my cheques dishonoured and getting myself stripped of my new commission. When I set out too late (as usual) to catch the Newhaven boat train from Victoria he drives me, weaving at speed through and around all the slow-witted weekend motorists, to pick it up at East Croydon.

The car remains a bond between us. And when the time finally comes for me to start taking up his disputed

£

115 a year (which in practice he has generously increased to

£

150), and I'm scrambling to get from my last day in the army to my first day of term as an undergraduate, he drives me to Cambridge. Or rather â two birds with one stone â allows Jill, who is now learning in her turn, to drive us both.

He comes up to Cambridge a number of times over the next three years, sometimes on his own, sometimes with Jill, sometimes with his friend Kerry, once, I think, even with Elsie. I've always remembered myself as being shamefully unwelcoming, but my diary suggests that I behave somewhat better than I thought. In summer I take him punting, in winter walk him round in the misty lamplight of the Fenland dusk. Give him lunch in my favourite Indian restaurant (where the girl who has just most painfully dumped me is sitting with her new boyfriend at the next table). I even go to watch cricket with him.

My feelings about all this are not entirely unambiguous. Tea at the Blue Boar is âsurprisingly successful', but tea in my rooms is not: âCould scarcely bear my family, particularly father.' I have the impression, though, that he gets a bit of a kick out of these visits. He may even assure me, with the usual knowing wink, that it's not a bad old university I've got myself into. A son at the Varsity (as he probably thinks of it) may seem to him to go rather well with the Harrods suits and shirts.

Then when I come down, at the end of my three years, all his old suspicions and forebodings return with a rush. âPass your exams?' he asks me with careful casualness, as if they had been

the Elephant and Castle. I tell him I got a two-one. The esoteric university jargon puts his back up at once.

âA do-what?'

âA

two-one

.'

âWhat's that supposed to be?'

âWell, you can get a first, or a two-one, or a two-two, or â¦'

âHold on.' Quick as ever to take the point. âSo you were supposed to get a first? And you didn't? You've failed? I knew it wouldn't come to anything, going to Cambridge.'

All right, I've failed. Gratifyingly. I've wasted the last three years â wasted the first twenty-four years of my life. Now I'm going to waste the rest of it. He's arming himself against disappointment once again.

âWell, you've had your fun,' he says heavily. âNow you've got to start looking for a job.'

âI've got one,' I tell him. I hope I manage to sound offhand about it in my turn.

â

Got

one?' He looks at me carefully. He's probably remembering that I have actually sometimes found paid employment in the past, in spite of his scepticism. I've been a Christmas postman, a van driver, a warehouseman, a sawyer's mate. Perhaps, he's thinking, I did rather better at one of these occupations than he'd supposed. It's not Christmas, and I dented the van, but maybe the sawmill thought highly enough of me to take me back. âWhat sort of job?' he asks warily.

âReporter,' I tell him. âOn the

Manchester Guardian

.'

Quick as he is, it takes him a moment or two to think of a comeback to this. He may not realise that to have got this particular job is for me more or less the equivalent for him of a five-horse accumulator coming up at Sandown, but he has certainly heard of the

Manchester Guardian

. Has never read it, but has told me, with his usual vicarious connoisseurship, what a reputation it's got.

âAre they paying you?' he says finally. âOr are you paying them?' This is a retreat under cover of humour. I think. For the second time the

Guardian

has come to my rescue. And a few days later he

comes back from the office and says in a rather different tone of voice that he has been talking to his colleague Greenwood, whose son has also just come down from Cambridge â and also with a two-one. âGreenwood,' concedes my father reluctantly, âsays a two-one's some kind of pass.'

So I haven't entirely wasted my life after all. He may not have to spend his declining years keeping me from destitution.

When the day arrives for me to move to Manchester, he drives me once again. From Stoke-on-Trent north it rains. The windscreen wipers beat hypnotically back and forth, and he tells me some of the stories about his childhood that I've mentioned in this book. We sing the old songs. âFling wide the ⦠fling wide the ⦠fling wide the gates.' âCome, come, come and make eyes at me â¦'

Now I really am finally flying the nest; no more 48s or long vacations. So far as I can recall it's the last time that he has a chance to drive me anywhere.